Latinx Files: Why do we need Latinx heroes?

- Share via

When I was in high school, I won an essay contest whose prize was a weeklong trip to Washington, D.C. I don’t recall the precise essay prompt; I just remember that we had to write about a hero of ours and how they inspired us to do good.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

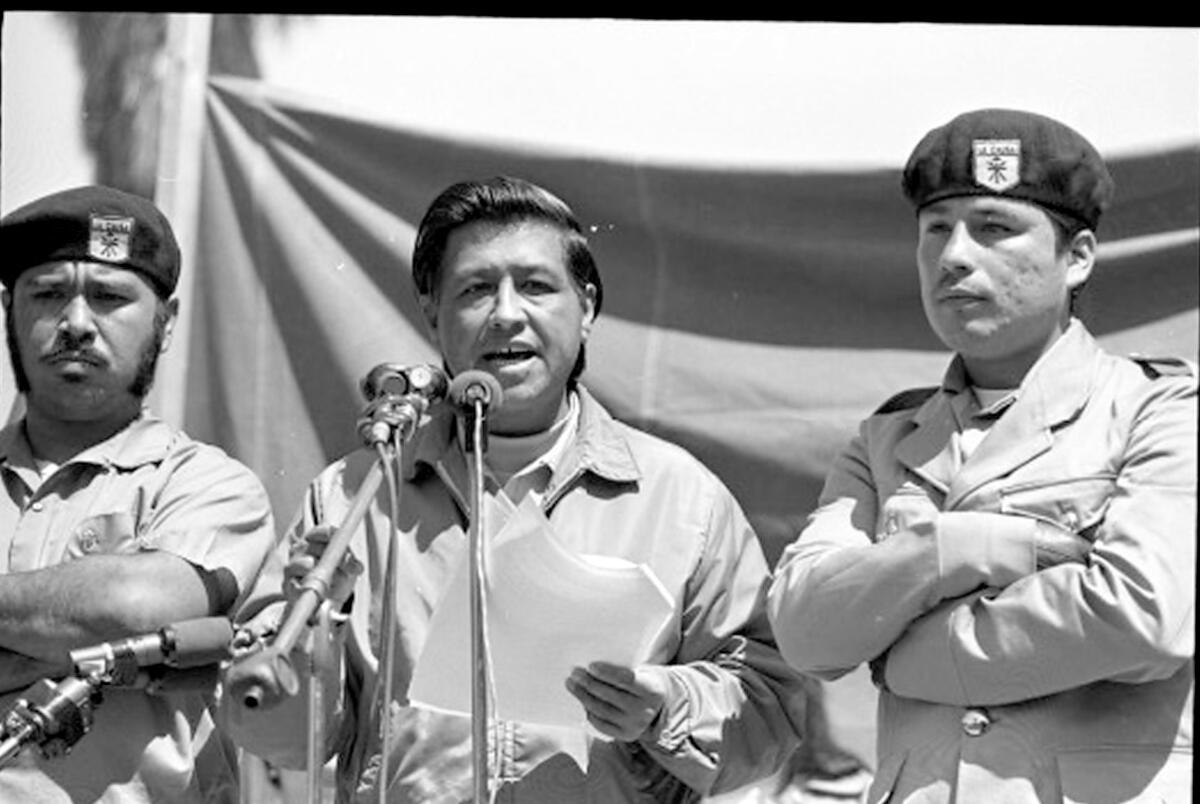

I picked Cesar Chavez mostly because he was the only famous Mexican American I could think of, and I felt like his mission to bring dignity and a fair wage to farmworkers — the stuff I’d learned about at school — was something I could easily align myself with. I, too, wanted to make this a better world for my people.

A few years later, I wrote a letter to the editor of my college paper (ugh, I know, I was — am? — that guy) admonishing my school’s MEChA chapter for launching a campaign to get Cesar Chavez’s birthday turned into a federal holiday. It wasn’t that I objected to their larger effort. What I took issue with was their claim that Chavez fought for the rights of immigrants.

At some point between when I wrote the essay and the letter, I learned that in his efforts to achieve his goals, Chavez organized “wet lines,” essentially farmworkers-turned-border minutemen who called la migra on undocumented workers. Being from an extended family with mixed immigration status, I decided then and there that Chavez was no longer my people.

I’ve been thinking about these two incidents a lot after reading my colleague Gustavo Arellano’s latest column, which details his own complicated feelings towards the late labor activist. In it Arellano brings up some of Chavez’s other shortcomings — his role in erasing Filipino farmworkers from his movement — before reaching the conclusion that these people we call heroes are human, and humans are inherently flawed. Chavez isn’t an exception.

“History — life — is not an easy-peasy snap-judgment call,” Arellano writes. “To paraphrase Oscar Wilde: Every saint had a past, and every sinner has a future.”

Yesterday was Cesar Chavez Day, a federally recognized holiday since 2014. Do I think he deserves his own holiday? Yeah, probably. There’s a day for everything — in addition to being April Fool’s Day, it is also “National One Cent Day” and “Take Down Tobacco National Day of Action” — so why not give one to one of the greatest leaders of the labor movement?

I understand the desire to protect Cesar Chavez’s legacy. It’s not like Latinxs have many well-known heroes to begin with. In 1983, The Times conducted a poll (as part of the Pulitzer Prize-winning series “Latinos”) asking the city’s Latinx residents to name their heroes. Respondents struggled with that question.

“Other than Fernando Valenzuela, I couldn’t tell you who are our heroes,” said Francisco Perez of East L.A. “We don’t have that many picked up by the media.”

It was the lack of options that led Times readers in 1983 and me in high school to pick Chavez as our default choice. But that alone shouldn’t shield him from the truth of who he was and what he did.

I don’t have to look far to understand that heroes can be flawed and human. After all this time, I’ve come to the realization that the only people I truly consider heroic are my own parents. To this day I am still in awe of the life they’ve been able to build for us despite limited resources and opportunities. I can also attest to the fact that they are flawed individuals.

It’s possible to admire someone while still being aware of their imperfections. It’s when you put them on a pedestal that you run into issues. Some people’s desire to elevate things or people often goes hand in hand with other people’s desire to knock them down.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Join us for Fernandomania @ 40

The Los Angeles Times is inviting its paying subscribers to the exclusive premiere of the first installment of Fernandomania @ 40, the Times’ multi-episode documentary series that examines star pitcher Fernando Valenzuela’s impact on the Dodgers, Major League Baseball and the Latino community in Los Angeles 40 years ago.

After a screening at 6 p.m. Thursday, April 8, Times columnist Gustavo Arellano, deputy sports editor Iliana Limón Romero and Mexican-American baseball expert Richard Santillán will discuss the fan frenzy surrounding the humble Mexican pitcher’s record-setting rookie season and answer questions from subscribers.

Registration opens tomorrow morning. You can sign up here.

Meet our Latinx staff: Jorge Castillo

The Los Angeles Times employs more than 100 Latinx journalists. One of the goals of this newsletter is for you to meet them all. This week, we highlight Jorge Castillo, who covers the World Series champion Los Angeles Dodgers of El Lay. Today is Opening Day, which means that you should follow his work and also check out the liveblogs the sports desk will be doing for every series the Dodgers play. They will all appear here. You can find the inaugural one for the Rockies series here.

Let’s get this out of the way first: I’m not from the West Coast, and I’m not Mexican American. I was born and raised in Worcester, Mass. My parents are from Puerto Rico, and most of my family is still on the island.

I moved to Los Angeles in September 2018 to cover the Dodgers for the Los Angeles Times because it was an incredible opportunity. And I know The Times sought me for the job because I am a bilingual Latino capable of telling stories few other baseball writers across the country can.

While around 40% of Major League Baseball players are Latino, the American mainstream media focused on covering them lags far behind. I like to think that is an advantage for me. I’m able to connect with Latino players, coaches and agents just by speaking Spanish.

But there’s also a cultural component, an understanding of where they come from, how they may think and the struggles of coming from Latin America to a strange place to make a living. I know that because my parents and other relatives have done it.

The Dodgers aren’t exactly loaded with Latinos. It’s actually jarring. Their projected Opening Day roster will have just three — two Mexicans (Julio Urías and Victor González) and one Puerto Rican (Edwin Ríos). They won’t have any Dominicans or Venezuelans — at least to begin the season.

Still, I’ve been able to use my skill set for stories others can’t tell in my short time in Los Angeles. Last season, I worked with Kiké Hernández on a series of diary entries to give readers — in English and Spanish — a behind-the-scenes look at the strangest year in MLB history. I’ve written about González’s rocky and sudden rise to the majors, Dennis Santana’s love of birria, and Jairo Castillo, a Dodgers scout from the Dominican Republic who died from complications from COVID-19.

There are plenty of more stories to tell about the growing number of Latinos in the sport. As much as it is my job to cover the Dodgers as a whole, I know I have a responsibility to tell those in particular.

Things we read this week that we think you should read

— The UCLA men’s basketball team has reached the Final Four for the first time in 13 years, and their unlikely run at a title has been partially fueled by paisa power. Jaime Jaquez Jr., a Mexican American guard/forward from Camarillo, Calif., has been crucial for the Bruins. Want to learn more about the mustachioed baller? Our Esquina has a great profile on Jaquez — and if you want to go way back, you can also read this story written by The Times’ prep school writer Eric Sondheimer, who is a living, breathing encyclopedia of Southern California high school sports. Speaking of Sondy, he also recently launched the Prep Rally newsletter, which you can sign up for here.

— For L.A. Taco, Melissa Montalvo wrote about keeping the memory of departed loved ones alive through food. In this loving tribute to her abuelito, Montalvo writes about trips to Puerto Nuevo, Baja California, to eat lobster and how she plans on keeping up this tradition going.

— For Guernica magazine, Emily Kaplan wrote about the life and untimely death of Antonio Sajvín Cúmes, an undocumented Indigenous person from Guatemala with whom she struck up an unlikely friendship while the two were living in Brooklyn. Early on, Sajvín Cúmes had told Kaplan that he wanted to write a memoir called “The Life of a Migrant” in which he would warn others that the American dream was nothing but a lie. He never had the chance to write it; Sajvín Cúmes died of COVID-19 in 2020 far from his hometown of Santa Catarina Palopó, Guatemala.

— My colleagues Kate Linthicum and Molly Hennessy-Fiske wrote about the infuriating trend of rich Mexicans flying to the U.S. to get vaccinated. Particularly egregious was the account of a man from the outskirts of Monterrey chartering a private jet to Brownsville, Texas, so he could drive to nearby rural Los Fresnos to get vaccinated. This report comes just a week after Mexican officials admitted that COVID-19 deaths in the country were actually 60% higher than previously claimed.

— For LAist, Dr. Oswaldo Hasbún Avalos wrote a personal essay decrying how his immigrant community is being used to produce COVID-19 “trauma porn.”

“Should we reduce the lives of these complex individuals to provocative pictures on what may be their deathbed to applaud the efforts of what are still largely white saviors,” Hasbún Avalos asks. “Would we want our own family members showcased in this way?”

The best thing on the Latinternet: Angering the rich folk with them low-lows, girl

Last Wednesday, Texas Monthly wrote about the residents of a new luxury condo building in East Austin having their feathers ruffled over the fact that they had moved in next to Chicano Park, which has been the meetup place for a local car club for decades.

For those unfamiliar with Austin, the Eastside has historically been the Black and Latinx part of the city. This was by design; in 1928 the city approved a master plan that basically pushed non-white folk to that part of town. In recent years, however, that area has been hit hard by a wave of tech bros and others with a penchant for displacement. In 2019, the 78721 ZIP code (which covers only part of this area) was one of the 10 fastest-gentrifying ZIP codes in the country.

Unfortunately for these gentrifiers, it looks as if the car club is is here stay. It seems that word of the story got out and people came out in full force. You love to see it.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.