‘We don’t just study’: Inside Asia’s bloody history of student-led protests

- Share via

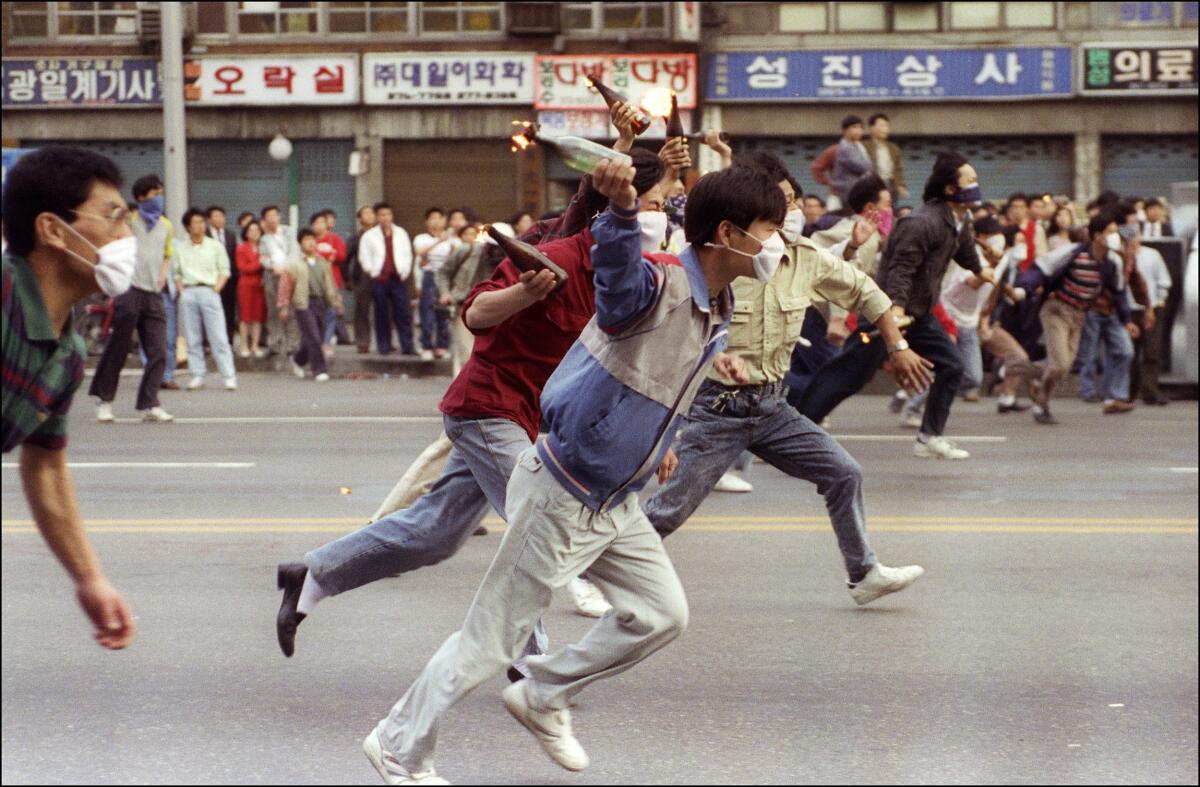

SEOUL — As a college student, Lee Kyung-lan grew adept at assembling Molotov cocktails using paint thinner and soju bottles and learned that wearing a mask stuffed with toothpaste-laden tissue made tear gas more bearable, even if it wouldn’t help with blistering on her skin.

Week after week, she took to the streets with classmates and chanted at the top of her lungs: for democracy, for direct elections, for constitutional reform. The students sketched out battle plans against riot police on pieces of paper they passed around, memorized, then burned. Twice, she was arrested. Once, her head was rammed against the side of a truck by police.

That was the 1980s in South Korea, then ruled by an army general who took power in a military coup.

Three decades later, the streets of Hong Kong are looking a lot like South Korea did in the 1980s. Young protesters leading the charge and a restless populace coming to their support. Increasingly violent clashes with riot police. An unrelenting authoritarian government with formidable military might.

Students are also at the forefront of recent widespread protests in Indonesia against new laws that demonstrators say weaken the country’s anti-corruption agency and against plans to criminalize and increase punishment for sexual activities. At least two have been killed in clashes with police, in some of the biggest protests since a student-led uprising in 1998 that toppled strongman Suharto.

Asia has never had a single defining moment like the Arab Spring, the surge of uprisings that swept through Arab nations in the early 2010s. But many countries in Southeast and Northeast Asia have rich histories of student-driven movements that have inspired, triggered and fed off of one another, bringing waves of social unrest and resistance against authoritarianism over the decades.

It was Thai university students who led the ouster of a military government in 1973, bringing about a short-lived democratic government. Taiwanese students rose up in 2014, seizing parliament in Taipei in protest of a trade pact with mainland China in what became known as the Sunflower Movement.

The summer of 1987 marked a watershed for South Korea, now one of Asia’s most stable and thriving democracies. That year, the deaths of two college students — one who drowned while being tortured by police, the other struck in the head by a tear-gas canister — sparked protests so fervent that the government caved in and agreed to hold direct elections.

The parallels have not been lost on protesters in Hong Kong, where a South Korean protest song translated into Cantonese — “March for the Beloved” — has rung out in the streets, and multiple public screenings have been held for “1987: When the Day Comes,” a recent blockbuster movie dramatizing South Korea’s pro-democracy movement.

This month, Joshua Wong, the 23-year-old who has become one of the most recognizable faces of the Hong Kong protests, posted two photos on Twitter depicting police crackdowns of protesters decades apart in the two areas and the words: “1980.5.18 in South Korea / 2019.10.1 in Hong Kong.” The post was retweeted more than 25,000 times.

Lee Tae-ho, who was a student protest leader in South Korea in the late 1980s, traveled to Hong Kong in late July at the invitation of activists there to talk about the pro-democracy movement in South Korea.

He also talked about the months-long peaceful candlelight protests in 2016 and 2017 that led to the impeachment of then-South Korean President Park Geun-hye in a corruption scandal.

“We exchanged information about each of our experiences,” said Lee, who remains an activist with the Civil Society Organizations Network in Korea and maintains connections with leaders of democratic movements in the region through a group called the Asia Democracy Network. “I described efforts we made in Korea to keep protests peaceful ... how unforeseen clashes can lead to violence that can give authorities an excuse for more oppression.”

Erik Mobrand, professor of Korean studies at Seoul National University who is an expert on South Korea’s democracy and politics elsewhere in Asia, said there are “strong parallels” between the movements in South Korea and Hong Kong — both driven by young people aided by momentum built up over a period of years.

But as much as South Korea’s example might be heartening, he said, Hong Kong’s unique political situation of being semiautonomous under Beijing’s rule leaves far less leeway for Hong Kong’s leaders to find a compromise with protesters.

“The differences in terms of what the regime can do in response are quite stark,” he said, adding that the recent shooting of a protester might act as a catalyst. “One thing we learned from South Korean political history is that when tragic things happen to young people at the hands of police, the political situation escalates.”

Even so, student movements can catch on beyond borders, language and political systems because the young in one country can identify with the frustrations of those protesting in another, said Meredith Weiss, a political science professor at the State University of New York in Albany who has studied student activism in Asia.

“Students can relate ... there’s an automatic affinity. ‘Wow they’re doing that, we can too,’” she said. “The content might not be the same, but this is something we as students can do, we don’t just study but rise up against power.”

In South Korea, many of those who previously took part in student uprisings are now in charge of running the country, many of them prominent lawmakers, scholars and government officials. In fact, President Moon Jae-in had been expelled from school and repeatedly jailed for taking part in protests against the dictatorship.

Even so, they have largely remained mum on protests in Hong Kong, wary of incurring the wrath of Beijing, by far South Korea’s most important trading partner.

Lee Kyung-lan, the onetime college student protester, is now a 53-year-old mother of two.

The events in Hong Kong, for her, are a poignant reminder of her college days. Student activists of her generation knew full well they were risking their lives in the fight, she said. Just a few years earlier, in 1980, troops had laid siege to and opened fire on protesters in the southern city of Gwangju, killing hundreds.

On June 9, 1987, she was taking part in protests outside the gates of her university in central Seoul. Rather than shoot the tear gas into the air as was typical, riot police appeared to aim low, directly at the students, she recalled. Her classmate, Lee Han-yeol, was struck in the head, fell into a coma and later died.

His death became a rallying cry. By late June, authorities announced they would reinstate direct elections as demanded by protesters.

During the protests of 2016 and 2017, Lee took part in the peaceful candlelight protests with her adult son and daughter, who were in their early 20s, around the same age she’d been during that restive period in 1987.

It hit home to her that she and her children were now exercising the same rights she and her classmates had fought so dearly for decades earlier, she said.

“Back then, we’d get rained on with tear gas immediately,” she said. “Now, I can voice what it is I want without any of that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.