- Share via

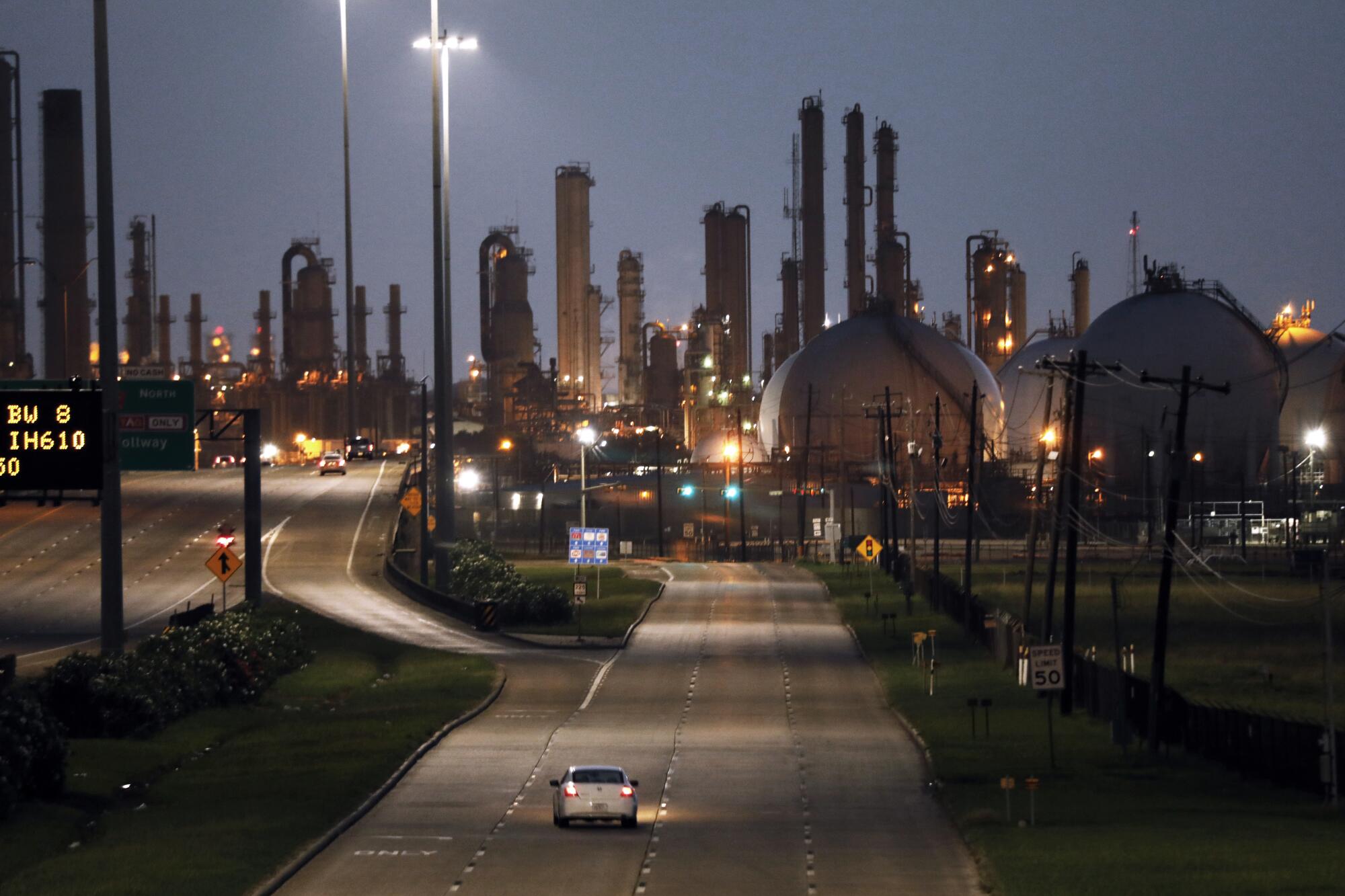

Baytown, Texas — In the shadow of oil refinery towers that have risen over this Gulf Coast town for generations, Effie Williams, an out of work pipe-fitter and single mother, watched a man mow the grass and wondered how much longer she could pay the bills.

Williams, 29, was furloughed in April, when the coronavirus spread across the state. For now, she has enough savings to get by on and cover the $1,298 rent for her three-bedroom brick ranch house, but she’s not sure how long this historic slowdown will last or what will happen to her and her children.

“They say we’re not starting back up until January 2021,” Williams said.

Little is guaranteed. These are uncertain days of long lines at food banks, extra prayers at church, nose swabs in parking lots, a time when the owner of a pawn shop down the road reaches for his gun if too many people come in at once.

Coronavirus has stunned Baytown’s oil-based boom/bust economy: Nearly a quarter of residents were unemployed, nearly twice the state average and 10% more than in neighboring Houston, according to the latest report in May. As of this week, the Gulf Coast region led the state with the most unemployment claims filed, nearly 114,000, many of them oil and gas workers, according to the Texas Workforce Commission.

Last week, Gov. Greg Abbott slowed Texas’ reopening due to a spike in infections and hospitalizations, particularly in Houston, center of the state’s oil and gas industry. He closed bars, reduced restaurant capacity, limited gatherings and for the first time required people to wear masks in public in areas with 20 or more COVID cases, including Baytown.

Baytown — a city of 90,000 about 30 miles east of Houston on Galveston Bay — has had about 400 COVID-19 cases and eight deaths. The mayor announced that police, already strapped during the pandemic, would not enforce the mask order or fines. A bar owner in a neighboring refinery town joined two dozen other owners and residents suing the governor over the closures. Many Baytown residents said they worried about COVID-19 but were equally concerned about the economy, which has long ensured high school graduates a middle class lifestyle.

Daniel Herrera, 26, was mowing his family’s lawn this week after losing contract jobs as an electrician’s helper at nearby plants. Two of his four brothers were also electricians at the refineries. One just found work and had his own house across town. The other was jobless and lived with Herrera and their parents.

Part-time refinery work helped put Herrera through the University of Houston, where he was studying electrical engineering.

“There’s always a lot of jobs here,” he said.

The coronavirus may alter such prospects. The nature of this region — the 1980s roughneck film “Urban Cowboy” was shot not far from here in Pasadena — is cycles of good times followed by hard truths in a frontier mix of swagger and ingrained promise that the fortune beneath the ground will take care of those who live above it.

“We’re an oil town. We depend on it. That’s Exxon across the street,” said Ronnie Hill, 75, pointing from his pawn shop, where he said business has fallen 85% since the pandemic because, “people who ain’t working can’t spend money.”

Hill also rents out several houses but said about 40% of his tenants -- including unemployed oil and gas workers -- can’t pay. Downturns breed desperation, he said. These days, when several people enter his store to peruse watches, gold chains and other jewelry, Hill straps his .357 Sig Sauer pistol to his hip.

“We’re stressed out,” he said.

Recent studies have shown the economic downturn wrought by the pandemic in Texas has been felt more acutely among working class communities, where many are people of color who work in industrial plants, restaurants, hotels and other front line jobs.

“Our cities have been divided into people who have to go to work and people who can work from home,” said Bill Fulton, director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Houston’s Rice University.

Blue collar suburbs like Baytown were “suffering significantly,” he said, while gentrifying urban neighborhoods in Houston and other large cities were faring better even as COVID-19 cases spiked. Houston received millions in federal coronavirus relief, but smaller cities didn’t, Fulton noted, even as they lost jobs and tax revenue.

“Some of the smaller cities, especially those dependent on the hotel and sales tax, will be really suffering in coming years,” Fulton said, noting West Texas oilfield towns like Midland and Odessa have seen business slow to a standstill in recent months as producers plugged oil wells.

“The refineries in Baytown are still going, but how long is that going to last?” he said.

Texas cities were furloughing and firing employees this month, and state officials have ordered agencies to cut budgets. About 35% of Texas cities saw tax revenue decrease this year compared with last, according to a survey last month of about half of the 1,150 member cities in the Texas Municipal League.

“That’s much higher than we’ve ever seen,” said Bennett Sandlin, the league’s executive director.

Baytown Mayor Brandon Capetillo said more than half of the town’s $207-million budget comes from payments by 80 industrial districts, including oil companies, which have remained steady. So has sales tax revenue, although there’s a two-month lag in reporting, he said. While many oil and gas contractors have been laid off, Capetillo expects hiring to rebound, “once the virus is managed and under control.”

The city hasn’t laid off any of its 900 employees, he said, although they had to eliminate 300 part-time employees when they closed the city water park after a staff member tested positive for COVID-19 two weeks ago. Baytown hotels that were close to capacity with oil workers before the pandemic had slowly started to fill again before the governor paused reopening last week.

“It’s kind of a wait and see what happens over the next few months before things can ramp up again,” he said. “... My concern would be more so for the mom and pop small businesses in Baytown. They don’t have the type of operating reserves for months on end to maintain payroll.”

He talks to mayors in neighboring refinery towns along the Houston Ship Channel who say the same thing is happening in Deer Park, La Porte, Morgan’s Point and Pasadena. Their small businesses now reflect changing demographics. Most honky tonks have vanished, replaced by carnicerias, washaterias and quinceañera dress shops. Baytown’s Robert E. Lee High School is now accompanied by Lorenzo De Zavala Elementary, named after a Tejano pioneer.

Baytown Chamber of Commerce President Tracey Wheeler said she worried about locally owned restaurants like El Toro and Pipeline Grill, which closed two of their three locations during the pandemic.

“People we’re talking to at small businesses really had a hard time when we shut down,” she said. “I see some of them that are really struggling.”

Baytown workers are used to weathering oil busts and natural disasters like hurricanes, she said, but with the coronavirus downturn, “It all came at the same time. That’s the hard part of it.”

Recent drive-through food distributions have drawn long lines. Hearts and Hands of Baytown, a ministry of Iglesia Cristo Viene, has been distributing 60,000 pounds of food to 900 local families weekly, said Executive Director Nikki Rincon.

“The unemployed continues to rise. Many who were furloughed have lost their jobs,” said Rincon. “I think this will be a marathon, and it is hard to predict when we will see an upturn.”

After welder Victor Alvarez, a legal resident, was laid off two months ago, his wife — a U.S. citizen — left Baytown with their 10 year-old and 10 month-old sons to join family in Michoacan, Mexico. His older brother, also laid off, lined up work at Exxon last week only to see it canceled at the last minute.

Alvarez said some of his co-workers have tested positive for COVID-19 and survived. He worried more about the economy than the virus. He wasn’t sure whether to wait out the downturn, join his family in Mexico or travel somewhere else in the U.S. for work.

“My friends are going to other states because it’s closing in Texas,” he said.

But fellow unemployed oil worker Manuel Resendez wasn’t leaving Baytown.

“Oil and gas is what keeps Texas alive,” he said, fishing off a pier this week.

Resendez, 54, an industry safety manager, moved to Baytown from Houston two years ago and built a new home before he lost his job during the pandemic. So did his wife, who works in construction.

He hasn’t earned less than $70,000 annually for the past 15 years and can’t imagine where he could maintain a similar standard of living without a college degree.

“We’re just waiting on it to bounce back,” Resendez said. “For me, it’s Texas or nothing.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.