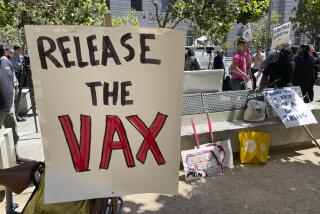

COVID-19 vaccine inequity: Inside the cutthroat race to secure doses

- Share via

PARIS — When the race for COVID-19 vaccines started, health officials knew the competition between rich and poor countries would be lopsided.

But few expected poor countries to be at the mercy of donations from the rich, or that the inequity would be this bad for so long. Poor countries have vaccinated 1% of their population, compared with 55% in the United States and about 25% globally.

The reasons for that gap return to decisions early on, in the initial bankrolling and distributing of the vaccines. Officials, primarily from the U.S. and Europe, have told the Associated Press they never thought to handle the situation globally. Instead, they jostled for domestic use.

COVID-19 unexpectedly devastated wealthy countries first, and many were also the places with the capacity and know-how to launch vaccine development.

Flaws built into a global purchase plan for poorer countries meant it couldn’t compete in the cutthroat competition to buy.

Intellectual property rights vied with public health for priority.

Rich countries expanded vaccinations to younger and younger people, even as poor countries went without. It’s like a famine in which “the richest guys grab the baker,” Strive Masiyiwa, the African Union’s envoy for vaccine acquisition, said recently.

The disparity was in some ways inevitable; taxpayers in wealthy nations expected a return on their investment. But the scale of the inequity, the stockpiling and the lack of a viable plan to solve a global problem have shocked health officials.

“This is where we were with the HIV pandemic. Eight years after therapeutics were available in the West, we did not receive them and we lost 10 million people,” Masiyiwa said. “We have no vaccine miracle.”

For years, the World Health Organization assessed pandemic readiness: The United States, European countries and India

ranked near the top. When the coronavirus hit, those assessments would prove horrifically optimistic.

The premise for pandemic vaccine development was that “rich countries would fund it for the developing world,” said Christian Happi, who advises the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovations, known as CEPI.

When the race was on to make and secure vaccines, the U.S. and Britain were leagues ahead — a lead they wouldn’t lose. Still, they and 22 countries in the European Union recorded declines in life expectancy unseen for decades.

But all those countries had a major advantage: They were home to the companies with the most promising vaccine candidates, advanced production facilities, and the money to fund both.

On May 15, 2020, President Trump announced Operation Warp Speed and promised to deliver vaccines by New Year’s.

With unparalleled money and ambition, Warp Speed head Moncef Slaoui was more confident than his counterparts in Europe. He signed contracts almost without regard to price or conditions.

“We were frankly focused on getting this as fast as humanly possible,” Slaoui said.

Operation Warp Speed supercharged the global race as did the U.S. Defense Production Act, which barred exports of raw materials and, eventually, of the vaccines themselves.

Two weeks later, COVAX — the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access program — was officially formed. The Serum Institute of India would be its core supplier.

COVAX had the backing of the WHO, CEPI, vaccines alliance Gavi and the powerful Gates Foundation. What it didn’t have was cash to secure contracts.

A plan from Costa Rica and the WHO for a technology-sharing platform to expand vaccine production foundered. No company agreed to share its blueprints, even for a fee — and no government pushed them, according to people involved in the project.

In the U.S., manufacturing and the trials went on in parallel, which is where the risks from taxpayers and the companies paid off. Europe and Britain also scaled up manufacturing.

This wasn’t an option in Africa, where the WHO’s expert in vaccine development, Richard Mihigo, said the brutal lesson learned was “how dependent we were on imports.”

Doses were stockpiled in Europe and North America and a few countries that paid a premium. COVAX was still getting promises instead of cash.

On Dec. 8, Britain became the first country to start widespread vaccinations. Six days later, the U.S. launched its own campaign. On Dec. 26, the European Union followed suit. China and Russia had been vaccinating even before releasing data from their homegrown inoculations.

COVAX delivered its first vaccines Feb. 24, to Ghana, a load of 600,000 AstraZeneca doses manufactured in India, but supply and distribution were spotty. The gulf with wealthy countries was growing by millions of doses every day.

Making vaccines isn’t a simple process, and pharmaceutical plants started to fall behind.

AstraZeneca announced repeated delivery cuts to Europe. Pfizer’s production briefly slowed. There was a fire at an Indian vaccine plant construction site. Moderna cut supply to Britain and Canada.

In the U.S., officials tossed out millions of corrupted vaccine doses from a Baltimore plant after discovering that workers had inadvertently blended ingredients from two different vaccines.

Then India, amid its own COVID-19 surge, blocked export of its vaccines until at least the end of 2021.

When Moderna and Pfizer created new production lines, it was in the European and American manufacturing networks that had as much stake as anyone in both ensuring the highest standards and keeping promises not to abuse intellectual property related to the messenger RNA vaccine-making process.

For the pharmaceutical industry, mRNA is the ultimate confirmation that hard work and risk-taking is rewarded. And those companies keep tight hold on the keys to their successful vaccines.

Many public health officials have pushed for technology transfer during the pandemic. Initially resistant, the Gates Foundation now favors sharing.

A recent meeting of the WHO’s vaccine allocation group disbanded with nothing accomplished, because there was no vaccine to allocate. “Zero doses of AstraZeneca vaccine, zero doses of Pfizer vaccine, zero doses of J&J vaccine,” said Dr. Bruce Aylward, a senior WHO advisor.

Both Trump and Biden administration officials reject the notion that any country would share vaccines until they’d protected their own, including teenagers.

“We had a responsibility to what I say, ‘Put on our own oxygen masks before helping others,’” said Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky in May.

COVAX now must rely on uncertain donations, with most of the promised doses pushed to 2022.

Dr. Ingrid Katz, a researcher at the Center for Global Health at Massachusetts General Hospital, said the key question is whether vaccines and essential medications are a commodity or a right.

“You have the source of decision-making sitting with very few people who have a lot of wealth and are essentially making life-and-death decisions for the rest of the globe,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.