- Share via

NEW YORK — Kristina Peterson anxiously tapped the heels of her boots on the tile floor inside the brightly lit lobby. Moments earlier, she had given her date of birth to an intake coordinator and answered an inquiry about the drug she planned to use.

“Heroin,” she said, referring to the tiny glassine envelope stamped “Off White” tucked inside her black purse.

For much of the last decade, Peterson has been hooked on heroin, her addiction becoming increasingly severe and public. Occasionally, she has shot up in quiet corners of subway stations as she waited for the E train back to the apartment where she lived in Queens. She sought to battle her addiction by taking methadone, but soon relapsed and was rushed to an emergency room after she overdosed in a park a few blocks from an elementary school.

“This is nothing I’m proud of,” she said on a recent afternoon while sitting inside an overdose prevention center, one of two in New York City that are the first authorized by a local government in the U.S. But “if I’m getting high, I want to do it here.”

Last year, a record 100,000 Americans died of drug overdoses. Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say the grim milestone stemmed from the stresses of the COVID-19 pandemic and an increasingly dangerous drug supply. In reaction, some elected officials and activists have ramped up efforts to open centers where drug users can be monitored as they shoot up and immediately receive treatment if they begin to overdose.

The pair of sites in New York City, privately funded and run by a nonprofit called OnPoint NYC, have been supported by former Mayor Bill de Blasio and his successor, Eric Adams, and are similar to centers long open in Canada, Europe and Australia.

Although they remain illegal under federal law, in recent days the U.S. Department of Justice has hinted that it intends to green light such sites — a drastic pivot from the Trump administration’s stance.

In the final days of the Trump administration, federal prosecutors prevailed in preventing a similar site in Philadelphia when a court ruled it would violate a 1980s-era law written to target drug use at “crack houses.” The U.S. Supreme Court declined to take up the case last year.

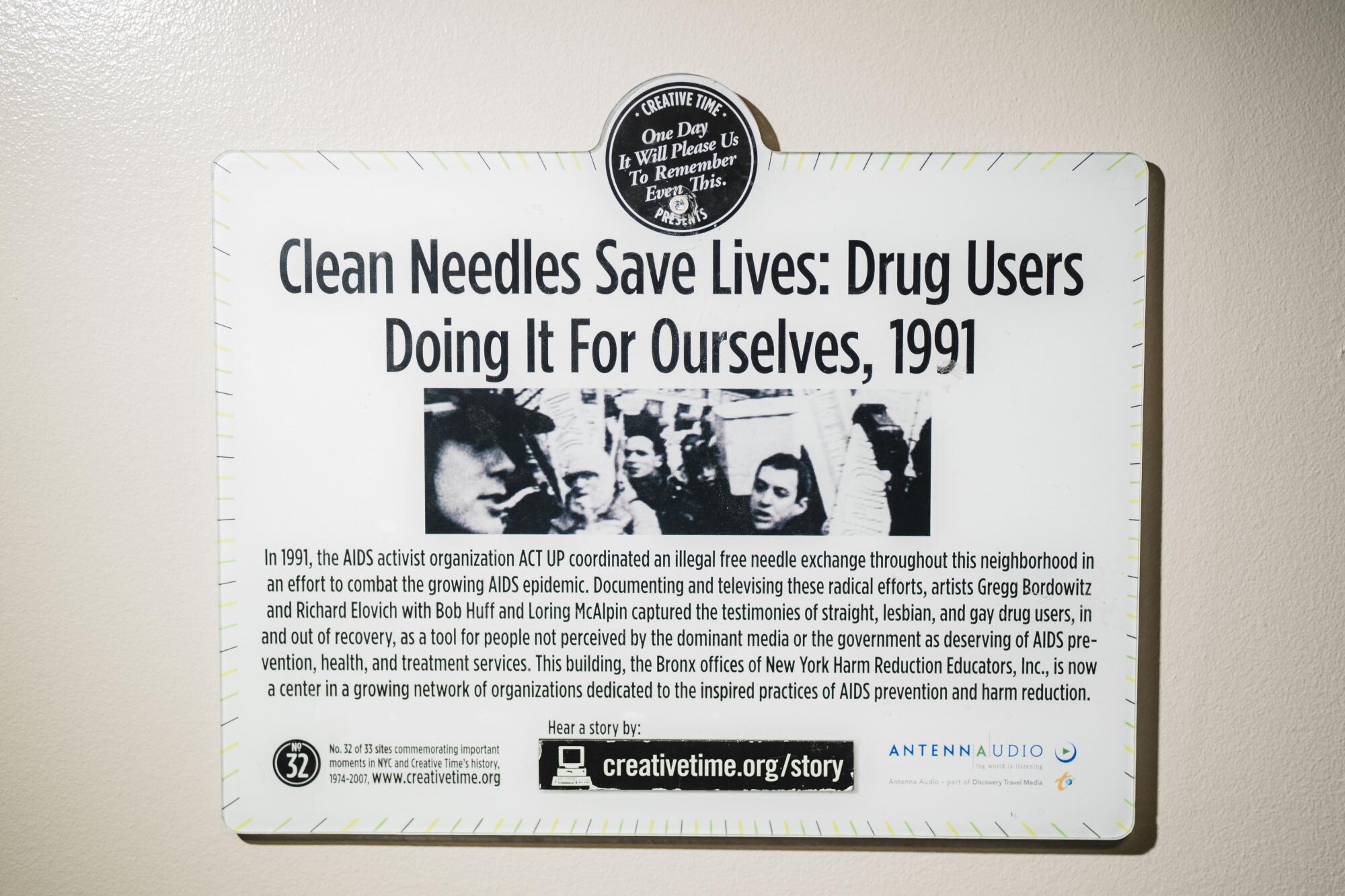

The concept of supervised injection centers has been discussed for years by activists who work in harm reduction in New York, San Francisco and several other major U.S. cities.

In California, the idea was struck down in 2018 by Gov. Jerry Brown, who vetoed a measure to try out such sites in San Francisco, saying that “enabling illegal and destructive drug use will never work.” Lawmakers in Sacramento this year are pushing to allow several Bay Area cities and the city and county of Los Angeles to approve entities to run such programs.

Though a few unauthorized facilities have operated under the radar, at least for short stints, in recent years the two centers here in New York are the first to be officially backed by city officials.

Besides the mayor, four of New York City’s five district attorneys support supervised drug sites.

Since OnPoint NYC’s headquarters opened in November on a quiet block in East Harlem, hundreds of drug users have begun to arrive daily at the four-story brick building. After offering details about what drug they plan to use, participants are provided with clean syringes, pipes or sterile cookers — tiny tea candle-like holders — to heat heroin.

Meanwhile, harm reduction counselors and fellow drug users keep an eye on one another, checking for dilated pupils or labored breathing.

When users begin to overdose, the harm reduction team is trained to treat them with naloxone, a drug sold under the name Narcan, which rapidly reverses an opioid overdose.

To date, OnPoint NYC’s two overdose prevention centers — the second of which is located in Washington Heights — have served 678 people and intervened in 134 overdoses, according to the New York City Department of Health.

“The simple truth is that overdose prevention centers save lives — the lives of our neighbors, family and loved ones,” said Health Commissioner Dr. Dave A. Chokshi in a statement.

Detractors argue that government entities and even private groups should be barred from taking any step that could enable dangerous, illegal behavior.

But that’s been the status quo for years, said Sam Rivera, executive director of OnPoint NYC, and tens of thousands of Americans die every year, many of them due to overdoses or infections that spread through sharing or reusing dirty needles.

“We are addressing a crisis,” Rivera said. “We must be proactive and meet those struggling with addiction where they are.”

Rivera’s group also provides medical and mental health care services to drug users in the New York area. In recent months, health officials from Los Angeles and San Francisco have visited to tour the facilities, Rivera said, adding that he’s hopeful that similar centers will eventually open in California and elsewhere.

“There must be a strong, comprehensive effort to combat overdose deaths,” he said.

The 59-year-old, who grew up on the Lower East Side and has worked in harm reduction for 30 years, said he has had several friends and family members battle drug addiction. Growing up, Rivera said, he recalls walking into his cousin’s apartment bathroom and finding him slumped with a needle in his arm.

“It’s a sight I can never unsee,” Rivera said. “This is an issue a lot of families are dealing with.”

Moreover, the drug supply has become exponentially more dangerous since then, Rivera said, as heroin is now cut with fentanyl, which can prove fatal even in infinitesimal doses.

In 2020, nearly 2,000 people died of a drug overdose in New York City, the highest number since reporting began in 2000. Last year, actor Michael K. Williams of “The Wire” fame died inside his Brooklyn apartment of an overdose of heroin laced with fentanyl. Recently, four men were charged in connection with his death.

Kailin See, who works alongside Rivera, helped open some of the first supervised injection centers in North America, in Vancouver, Canada. She battled addiction and has worked in harm reduction for years.

“These are more than numbers,” she said, tearing up. “These are human souls, these are lives who have been given another chance ... another day to live. There should be no judgment, just the realization that lives are being saved.”

Not everyone agrees.

U.S. Rep. Nicole Malliotakis, a New York City Republican, has urged the federal Justice Department to shut down the newly opened centers.

“Crime and fentanyl use are at record highs,” she said in a statement when the sites opened. “These centers not only encourage drug use, but they will further deteriorate our quality of life.”

Other critics have noted that both centers are located in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods, the same places where people have long been prosecuted at disproportionately high rates for drug possession or use. They argue that increased drug use is being encouraged in these neighborhoods, possibly leading to spikes in violence, and not in other parts of the city.

Backers of the centers, including Rivera, noted that a systematic review of overdose prevention sites concentrated in Vancouver found that whereas overdose deaths went down, there was no evidence of an increase in crime in the surrounding and nearby neighborhoods.

::

Peterson’s addiction traces back to a Vicodin prescription she got in 2008 to cope with excruciating pain from scoliosis.

“Sadly, I got hooked,” said Peterson, 39, who is from upstate New York. “I never wanted this.”

For several years, she shot up three times a day. Then she met her eventual husband, Ed, who also was addicted. They sought out methadone treatment together and eventually got clean.

Peterson said she bounced between waitressing jobs at restaurants in Manhattan and Queens. “Slowly, I was getting things together,” she said.

But in recent years, they both relapsed, the ills of addiction too much for them to overcome, she said. Fearful that they would die if they overdosed alone, the couple decided to only use together. Since 2019, she has overdosed three times. Once, Ed saved her life by administering Narcan that a fellow user had on hand.

Peterson currently uses methadone but also injects heroin once or twice a week. She’s sought counseling and has, at times, gone several weeks without using. Still, addiction pulls her back into its grasp. After hearing about the overdose prevention center from other users, she tries to come whenever she feels the need to shoot up.

“None of us wants to be here,” she said. “But since we are addicted and using, it’s best to be safe.”

On a recent afternoon, the roar of the Harlem Metro-North Railroad station could be heard from inside the lobby as Peterson entered the supervised injection room. It has eight stalls that look like computer terminals in a library. The stalls, sterilized between each use, are situated near a table with clean syringes, cookers, fentanyl test strips and tourniquets.

As she walked into the room, Peterson spotted a familiar face and smiled.

“Hey, Rayce, my angel, great to see you,” she said.

Rayce Samuelson, a recent college graduate who grew up in Los Angeles, lost a friend to an overdose a few years ago. It’s what led the 23-year-old to a career in harm reduction. Since starting at the center, he’s helped reverse dozens of overdoses, he said.

“Great to see you,” he told Peterson. “Anything I can help with?”

“I need a lighter.”

“I got you,” he replied, handing her one.

Peterson pulled out the small envelope from her purse. The “Off White” stamp signified one of many names sellers use to differentiate batches of the drug.

Peterson took off her heavy winter jacket and rolled up her right sleeve and began scanning her arm for a vein. She spread the white substance onto the counter and slowly placed it into the cooker. She hovered the lighter underneath until it began to bubble. She had a clinically focused expression on her face — these days, Peterson said, she was primarily using only to escape from the sickness of withdrawals methadone doesn’t completely ease.

“I’m trying to keep my life together as much as possible,” she said.

There were four other users in the room, and Samuelson paced slowly from stall to stall, scanning for warning signs. In that moment, they all looked safe.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.