Home to Europe’s biggest monkeypox outbreak, Spain struggles to curb its spread

- Share via

BARCELONA, Spain — As a sex worker and adult film actor, Roc was relieved when he was among the first Spaniards to get a monkeypox vaccine. He knew of several cases among men who have sex with men, which is the leading demographic for the disease, and feared he could be next.

“I went home and thought, ‘Phew, my God, I’m saved,’” the 29-year-old told the Associated Press.

But it was already too late. Roc, the name he uses for work, had been infected by a client a few days before. He joined Spain’s steadily increasing count of monkeypox cases — the highest in Europe since the disease spread a few months ago beyond Africa, where it has been endemic for years.

He began showing symptoms: pustules, fever, conjunctivitis and tiredness. Roc was hospitalized for treatment before getting well enough to be released.

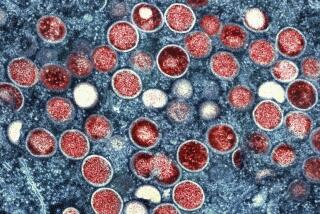

Spanish health authorities and community groups are struggling to check an outbreak that has already claimed the lives of two young men. They reportedly died of encephalitis, or swelling of the brain, which can be caused by some viruses. Most monkeypox infections cause only mild symptoms.

Spain has had 4,942 confirmed cases in the three months since the start of the outbreak, which has been linked to two raves in Europe, where experts say the virus was probably spread through sex.

The move aims to fast-track potential new treatments and vaccines for the disease, which about 1.6 million Americans are at high risk of contracting.

The only country with more infections than Spain is the United States, which has reported 7,100 cases.

In all, the global monkeypox outbreak has seen more than 26,000 cases in nearly 90 countries since May. There have been 103 suspected deaths in Africa, mostly in Nigeria and Congo, where a more lethal form of monkeypox is spreading than in the West.

Health experts stress that this is not technically a sexually transmitted infection, even though it has been mainly spreading among gay and bisexual men, who account for 98% of cases beyond Africa. The virus can be spread to anyone who has close physical contact with an infected person, their clothing or bedsheets.

So part of the complexity of fighting monkeypox is striking a balance between not stigmatizing men who have sex with men while also ensuring that vaccines and pleas for greater caution reach those currently in the greatest danger.

Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency in California over the spread of the monkeypox virus in order to “bolster the state’s vaccination efforts.”

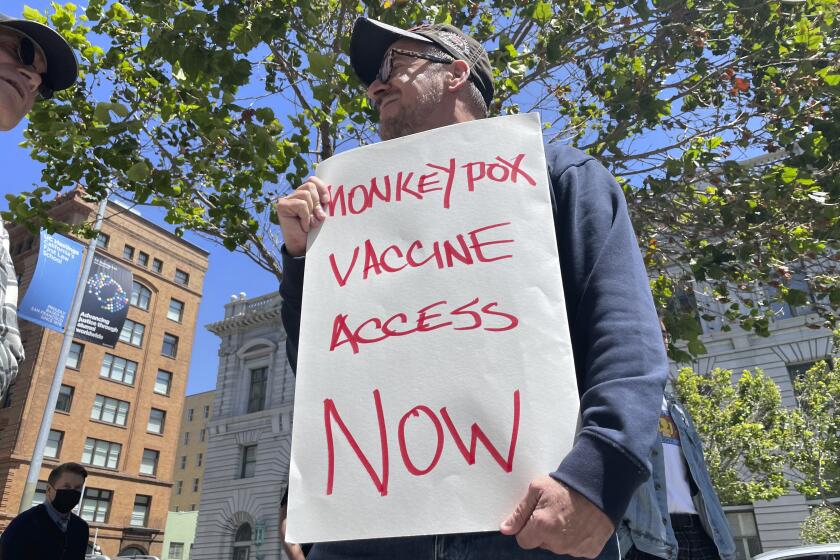

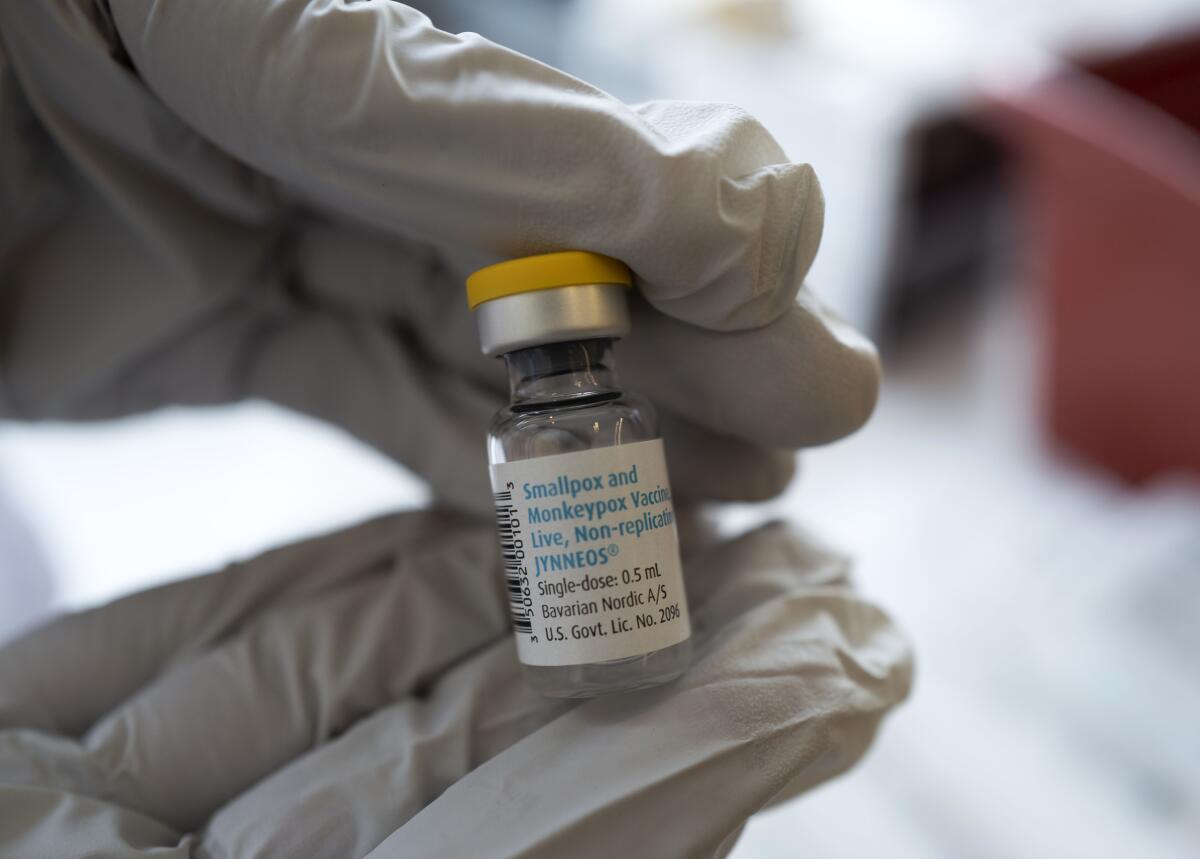

Spain has distributed 5,000 shots of the two-shot vaccine to health clinics and expects to receive 7,000 more from the European Union in the coming days, its health ministry said. The 27-nation EU has bought 160,000 doses and is donating them to member states based on need. The bloc is expecting 70,000 more shots to be available next week.

To ensure that those shots get administered wisely, community groups and sexual health associations targeting gay men, bisexual people and trans women are taking the lead.

In Barcelona, BCN Checkpoint, which focuses on AIDS/HIV prevention in gay and trans communities, is now contacting at-risk people to offer them one of the precious vaccines.

Pep Coll, medical director of BCN Checkpoint, said the vaccine rollout is focused on people who are already at risk of contracting HIV and are on preemptive treatment, men with a high number of sexual partners and those who participate in “chemsex” (sex with the use of drugs), as well as people with suppressed immune responses.

Although the monkeypox virus can affect anyone, some gay and bisexual men are worried about being once again branded as carriers of an exotic disease.

But there are many more people who fit those categories than vaccine doses.

“If we just consider the number of people [on prophylactic HIV treatment] plus the number of people with HIV, we are talking about some 15,000 people” just in Barcelona, Coll said.

The lack of vaccines, which is far more severe in Africa than in Europe and the U.S., makes social public health policies key, experts say.

As with the COVID-19 pandemic, contact tracing to identify people who could have been infected is critical. But while the coronavirus can spread simply through the air, the close bodily contact that serves as the leading vehicle for monkeypox makes some people hesitant to share information.

Top U.S. health officials say the country’s monkeypox outbreak can still be stopped despite rising case numbers and limited vaccine supplies.

“We are having a steady stream of new cases, and it is possible that we will have more deaths. Why? Because contact tracing is very complicated because it can be a very sensitive issue for someone to identify their sexual partners,” said Amós García, epidemiologist and president of the Spanish Assn. of Vaccinology.

Spain says that most of its cases are among men who have sex with men, and only 5% are women. But García said that that would even out unless the entire public, regardless of gender or sexual orientation, grasps that having various sexual partners creates greater risk.

“The same thing happened with AIDS/HIV, when at one moment the group of men who had sex with men was the most affected [before the disease spread to other groups], and that can become the path that this takes if we are not able to send a strong message to society,” García said.

Given the dearth of vaccines and the trouble with contact tracing, more pressure is being put on encouraging prevention.

Some are asking: ‘Would monkeypox have received a stronger response if it were not primarily affecting queer folks?’

From the start, government officials ceded the leading role in the get-out-the-word campaign to community groups.

Sebastian Meyer, president of the STOP SIDA association dedicated to AIDS/HIV care in Barcelona’s LGBTQ community, said the logic was that his group and others like it would be trusted message-bearers with person-by-person knowledge of how to drive the health warning home.

While community associations that represent gay and bisexual men have bombarded social media, websites and blogs with information on monkeypox safety, Meyer says there is still a lot to be done.

Meyer, who is on the monkeypox advisory boards for Spain’s national government and for regional authorities covering Barce- lona, believes fatigue from the COVID-19 pandemic has played a part.

Doctors advise people with monkeypox lesions to isolate until they have fully healed, which can take up to three weeks.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“When people read that they must self-isolate, they close the web page and forget what they have read,” Meyer said. “We are just coming out of COVID, when you couldn’t do this or that, and now, here we go again. ... People just hate it and put their heads in the sand.”

Meyer said that his group is currently brainstorming ways to revamp and relaunch their message.

“If you haven’t been selected for a vaccine, the answer is not to desperately hope that you’ll get one,” he said. “The answer is to be more careful. That is much better than any vaccine.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.