A Russian tactic for subduing Ukrainian towns: Kill or capture their mayors

- Share via

KYIV, Ukraine — Not long after Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine, soldiers broke down the office door of Melitopol Mayor Ivan Fedorov. They put a bag over his head, bundled him into a car and drove him around the southern city for hours, threatening to kill him.

Fedorov, 34, is one of more than 50 local leaders who have been held in Russian captivity since the war began Feb. 24 in an attempt to subdue cities and towns coming under Moscow’s control. Like many others, he said he was pressured to collaborate with the invaders.

“The bullying and threats did not stop for a minute. They tried to force me to continue leading the city under the Russian flag, but I refused,” Fedorov told the Associated Press by phone last month in Kyiv. “They didn’t beat me, but day and night, wild screams from the next cell would tell me what was waiting for me.”

As Russians seized parts of eastern and southern Ukraine, civilian administrators and others, including nuclear power plant workers, say they have been abducted, threatened or beaten to force their cooperation — something that legal and human rights experts say may constitute a war crime.

Ukrainian and Western historians say the tactic is used when invading forces are unable to subjugate the population.

This year, as Russian forces sought to tighten their hold on Melitopol, hundreds of residents took to the streets to demand Fedorov’s release. After six days in detention and an intervention from President Volodymyr Zelensky, he was exchanged for nine Russian prisoners of war and expelled from the occupied city. A pro-Kremlin figure was installed.

In Ukraine, rooting out those who aid Russia is a tangled, painful process. Hundreds of collaboration cases are being scrutinized.

“The Russians cannot govern the captured cities. They have neither the personnel nor the experience,” Fedorov said. They want to force public officials to work for them because they realize that someone has to “clean the streets and fix up the destroyed houses.”

The Assn. of Ukrainian Cities, or AUC, a group of local leaders from across Ukraine, said that of the more than 50 abducted officials, including 34 mayors, at least 10 remain captive.

Russian officials haven’t commented on the allegations. Moscow-backed authorities in eastern Ukraine even launched a criminal investigation into Fedorov on charges of involvement in terrorist activities.

“Kidnapping the heads of villages, towns and cities, especially in wartime, endangers all residents of a community, because all critical management, provision of basic amenities and important decisions on which the fate of thousands of residents depends are entrusted to the community’s head,” said Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko, head of the AUC.

Rights groups say Moscow’s practice of transporting captured Ukrainian civilians to Russia is illegal under international law. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, have vanished from Russian-occupied areas.

In the southern city of Kherson, one of the first seized by Russia and a key target of an unfolding counteroffensive, Mayor Ihor Kolykhaiev tried to stand his ground. He said in April that he would refuse to cooperate with the city’s new Kremlin-backed overseer.

Kirill Stremousov, deputy head of the Russian-installed regional administration, repeatedly denounced Kolykhaiev as a “Nazi,” echoing the false Kremlin narrative that its attack on Ukraine was an attempt to “de-Nazify” the country.

Kolykhaiev continued to supervise Kherson’s public utilities until his arrest June 28. His whereabouts remain unknown.

According to the United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, 407 forced disappearances and arbitrary arrests of civilians were recorded in areas seized by Russia in the first six months of the war. Most were civil servants, local councilors, civil society activists and journalists.

Moscow had suspended its participation in an agreement that allowed the shipment of millions of tons of Ukrainian grain through the Black Sea.

Yulia Gorbunova, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch, said the abuse “violates international law and may constitute a war crime,” adding that Russian forces’ actions appeared to be aimed at “obtaining information and instilling fear.”

The U.N. human rights office has warned repeatedly that arbitrary detentions and forced disappearances are among possible war crimes committed in Ukraine.

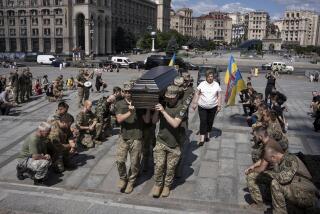

Several mayors have been killed, shocking Ukrainian society. Following the discovery of mass burials in areas recaptured by Kyiv, Ukrainian and foreign investigators continue to uncover details of extrajudicial killings of mayors.

The body of Olga Sukhenko, who headed the village of Motyzhyn, near Kyiv, was found in a mass grave next to those of her husband and son after Russian forces retreated. The village, with a prewar population of about 1,000, is a short drive from Bucha, which saw hundreds of civilians killed under Russian occupation.

Weeks after Russian occupation, rural areas outside Ukraine’s capital still yield forest graves. Exhumations remain a near-daily task for police.

Residents said Sukhenko had refused to cooperate with the Russians. When her body was unearthed on the outskirts of Motyzhyn, her hands were found tied behind her back.

Mayor Yurii Prylypko of nearby Hostomel was gunned down in March while handing out food and medicine. The prosecutor general’s office later said his body was found rigged with explosives.

Ukraine’s government has tried to swap captive officials for Russian POWs, but officials complain that Moscow sometimes demands Kyiv release hundreds of Russians for each Ukrainian in a position of authority, prolonging negotiations.

“It’s such a difficult job that any superfluous word can get in the way of our exchange,” said Dmytro Lubinets, Ukraine’s human rights commissioner. “We know the places where prisoners are kept, as well as the appalling conditions in which they are kept.”

When Russian troops crossed from Belarus into Ukraine in late February, pressing toward Kyiv, they were ordered to block and destroy ‘nationalist resistance.’

There has been no news about the fate of Ivan Samoydyuk, the deputy mayor of Enerhodar, site of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. Samoydyuk, abducted in March, has repeatedly been considered for a prisoner swap, but his name was struck off the list each time, Mayor Dmytro Orlov told the AP.

The 58-year-old deputy mayor was seriously ill when seized, Orlov said, and “we don’t even know if he’s alive.” At best, Samoydyuk is sitting in a basement somewhere, “and his life depends on the whim of people with guns,” he added.

More than 1,000 Enerhodar residents, including dozens of workers at Zaporizhzhia, Europe’s largest nuclear plant, were detained by the Russians at one time or another.

“The vast majority of those who came out of the Russian cellars speak of brutal beatings and electric shocks,” he said.

News Alerts

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Gorbunova, the HRW senior researcher, said torture “is prohibited under all circumstances under international law, and, when connected to an armed conflict, constitutes a war crime and may also constitute a crime against humanity.”

Each week brings reports of abductions of officials, engineers, doctors and teachers who won’t cooperate with the Russians.

Viktor Marunyak, head of the village of Stara Zburivka in the southern Kherson region, is famous for appearing in Roman Bondarchuk’s 2015 documentary “Ukrainian Sheriffs,” an Academy Award contender. The film explores the separatist conflict in eastern Ukraine that began in 2014. Although the film didn’t win an Oscar, it cemented Marunyak’s salt-of-the-earth reputation.

After Russian troops seized Stara Zburivka in spring, Marunyak held pro-Ukrainian rallies and hid some activists in his home. He was eventually taken prisoner.

Afghan special forces soldiers who were trained by the U.S. and fled after the U.S. withdrawal are being recruited by Russia to fight in Ukraine.

“At first, they put [electrical] wires on my thumbs. Then it seemed not enough for them, and they put them on my big toes. And they poured water on my head so it would flow down my back,” he told the AP. “Honestly, I was so beaten up that I didn’t have any impressions from the electric current.”

After 23 days, Marunyak was “released to die,” he said. Hospitalized for 10 days with pneumonia and nine broken ribs, he finally left for territory controlled by Kyiv.

Hubertus Jahn, a history professor at Cambridge University, said that from the time of Peter the Great onward, the tactic of imperialist Russia of co-opting locals targeted elites and nobility, with resistance often bringing Siberian exile.

During World War II, he said, “German SS units operated in a similar way,” by targeting local administrators in order to pressure residents into submission. Jahn called it an obvious strategy “if you don’t have the strength to subordinate a region outright.”

Historian Ivan Patryliuk of Kyiv’s Taras Shevchenko National University said municipal authorities in Soviet Ukraine often fled before Nazi occupation forces arrived, which “helped avoid mass executions of officials.”

“The kind of torture and humiliation [of] city leaders that the Russians are now perpetrating ... is one of the darkest and most shameful pages of the current war,” Patryliuk said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.