Tibet’s fiery, tragic trend

- Share via

Reporting from Beijing — During the winter break from high school, Tsering Kyi would spend her days tending the yak and sheep, always taking a book with her out to pasture. One of the few literate members of her family, bilingual in Chinese and Tibetan, her ambitions went far beyond those of her nomad parents.

“I want to do something for the Tibetan people,” the 20-year-old student from Maqu, in Gansu province, confided to an aunt last month.

A week ago, Tsering Kyi went into a public toilet at the vegetable market near her high school. She took off her chuba, a traditional Tibetan coat, and wrapped herself in a quilt and tied it on tightly with wire. Then she doused herself with gasoline and emerged in flames before the shocked vendors.

Tsering Kyi was the 24th Tibetan to die by self-immolation in the last year, a trend that has unnerved the Chinese government and infused the Tibetan independence movement with fresh energy.

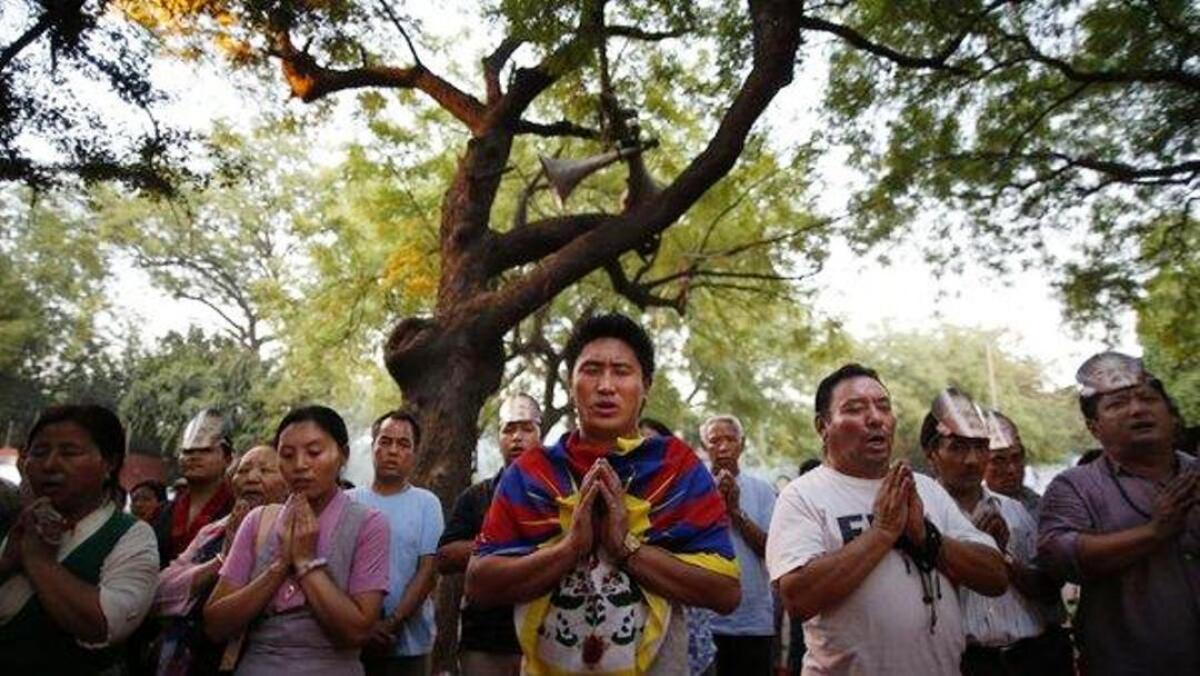

With emotions high as Tibetans on Saturday commemorate the 1959 failed uprising against Chinese repression that sent the Dalai Lama into exile, few expect the immolations to stop.

Most of the people who have immolated themselves were in their teens or 20s, a better-educated generation of Tibetans growing up in an age of rising expectations and heightened government pressure.

But the dead defy pigeonholing: a 32-year-old mother who left her four children sleeping at her in-laws’ house before she burned herself at dawn Sunday in front of the Kirti Monastery in the hotbed city of Aba. A young man who raised birds at a monastery in Sichuan province and was engaged to be married. An activist who was trying to banish Chinese words from the Tibetan language.

The oldest, a senior lama in his 40s from Qinghai province, left behind a nine-minute recording saying, “I am giving away my body as an offering of light to chase away the darkness.”

The Chinese government has tried to depict the immolations as copycat suicides by people they have variously described as criminals, terrorists and the mentally ill.

“They all have criminal records or suspicious activities. They have a very bad reputation in society,” Wu Zegang, a government official from Sichuan province, told reporters Wednesday on the sidelines of the National People’s Congress in Beijing.

In an effort to instill Chinese values, authorities have in recent years stepped up what they call “patriotic education” in schools and monasteries, forcing Tibetans to renounce the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet, and to study communist theory. Such efforts have backfired.

“There is an escalation of control and restrictions in daily life, and that burst out in frustration,” said Lobsang Jinpa, a 29-year-old former monk from Nyitso Monastery in Dawu, Sichuan province, which, like Gansu and Qinghai, has a large Tibetan population. He knew two people who died by self-immolation. He left China last year and now lives in Dharamsala, India.

The government has tried to downplay such motivations. China’s New China News Agency reported Wednesday that Tsering Kyi had been suffering from fainting spells after hitting her head on a radiator while playing in a classroom. “The medical treatment held up her studies and her school scores began to decline, which put a lot of pressure on her and made her lose courage in life,” the agency reported.

But a relative scoffed at that characterization. “She was normal, she was healthy,” said the relative, a woman in her 30s who asked that her name and location not be identified because of pressure from Chinese authorities. “She made a glorious sacrifice for her nation.”

Tsering Kyi was the third of four children of nomads. A photograph shows a girl with a cropped haircut and a pinched-cheek rosy complexion typical of young people on the windy Tibetan plateau.

“She was short and cute. She had a good singing voice. During celebrations or gatherings in the village, everybody would ask her to sing Tibetan folks songs,” the relative said. “She wasn’t shy.”

Because the family lived more than 20 miles from the county seat, Tsering Kyi didn’t go to school until she was 10, when her parents enrolled her and a younger brother and rented an apartment in town.

In the last decade, Tsering Kyi’s parents acquired the trappings of a more modern, middle-class life: electricity from solar panels, a motorbike and cellphones. At the same time, their income was squeezed by Chinese restrictions on where they could graze their animals, the relative said.

Her political activism began in 2008, when an uprising that broke out in the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, spread into Sichuan, Qinghai and Gansu provinces. Public schools began to restrict the teaching of Tibetan.

The next year, a popular Tibetan headmaster at Maqu Middle School, where Tsering Kyi was one of 1,500 students, was dismissed, sending dozens of students out to demonstrate in the streets. The teenage leaders were expelled and given stiff prison terms.

“She was very angry about what happened at her school,” her relative said. She had warned a few days before she died that she would immolate herself, but the relative said, “Everybody thought she was joking.”

After her death, the relative said, Chinese police locked the gates to the market and inspected vendors’ cellphones to make sure nobody had taken photographs that could be distributed on the Internet.

To Beijing’s dismay, the younger generation of better assimilated, Chinese-speaking Tibetans is often more radical than their parents or the Dalai Lama, who has called for Tibetan rights but not secession from China.

Lobsang Jamyang, who died by self-immolation Jan. 14 in Sichuan province, was the oldest son of farmers.

When he was young, his parents kept portraits of Mao Tse-tung and the Dalai Lama side by side. But their children weren’t as accepting of Chinese rule, said a cousin, Tashi, who is studying business in India.

Lobsang Jamyang became active in a group called the Tibetan Pure Language Assn., which would levy small fines against Tibetans who used Chinese words such as diannao (computer) or shouji (cellphone) instead of newly minted Tibetan words.

“He didn’t believe you could fight for more freedom within China. He wanted pure independence from China,” the cousin said.

Until last year, self-immolation was almost unheard of among Tibetans, unlike with Vietnamese Buddhists. One case was reported in 2009, and then none until March 16 last year, when a 20-year-old monk set himself on fire at the Kirti Monastery.

Although Chinese authorities swamped the monastery with riot police, building a barracks outside the front gate and posting 24-hour guards inside, the self-immolations continued. By October, they had spread to other monasteries and nuns began joining in.

“Now it is moving from the clergy to the lay people, and at that point it gets hard to stop,” said Robbie Barnett, a Tibet scholar at Columbia University.

Tibetans were stunned by the suicide of Rinchen, 32, whose four children ranged in age from a few months to 13 and whose husband had died a few months earlier. She was a nomad from a village about 35 miles away and had come to the Kirti Monastery to bring an offering of a meal for the monks, a Tibetan tradition, said Kangyang Tsering, a 32-year-old monk from Kirti who is living in India.

“For a mother to decide to leave her kids without any care in the world, it takes much more determination to commit such a desperate act,” Kangyang Tsering said in a telephone interview.

On Thursday, the respected poet Tsering Woeser, who is under house arrest in Beijing, released a public appeal for the immolations to stop.

“Regardless of the magnitude of oppression, our life is important, and we have to cherish it. Self-immolation in itself cannot change our reality,” she wrote in a statement also signed by two other prominent Tibetan intellectuals. “Only by staying alive can the will become a reality.”

Woeser said she doubted the appeal would be heeded.

“There is basically military rule right now,” she said. “It heightened the pressure, and if it continues, there will be more self-immolations to come.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.