Taiwan’s Kinmen island seeks to cash in on its past

- Share via

Reporting from Jinsha Township, Taiwan — Yang Yuan-tan dangled a fishing rod off the end of a narrow concrete pier that was once on the front lines of China’s efforts to take Taiwan.

The Chinese shoreline, just a mile away, is visible on a clear day from this spot on tiny Kinmen island’s northeastern tip.

For much of Yang’s childhood in a nearby village, the beach was off limits, bombarded almost daily by the Communists.

The retired farmer, 65, recalls picking up the shells, which were stuffed with propaganda leaflets, and taking them to his teacher. Children were instructed to hand them in without reading them, though naturally, some couldn’t resist.

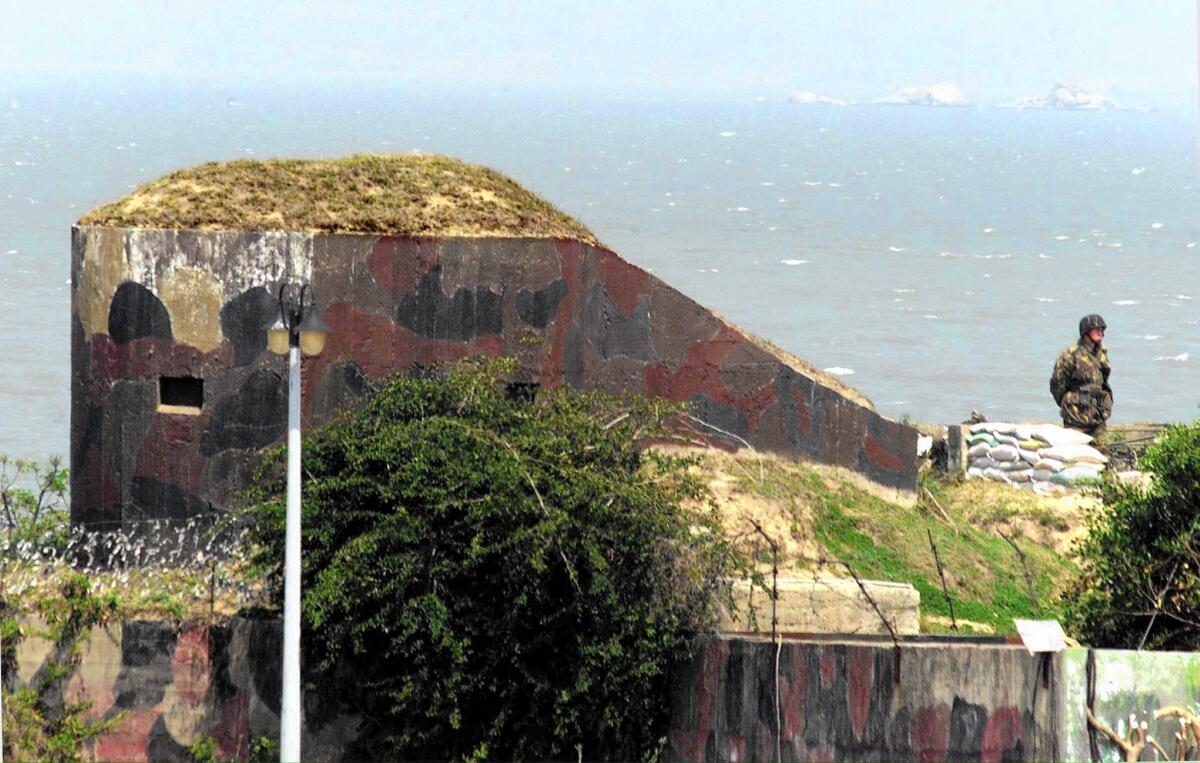

The beach at Mashan is lined with decaying concrete bunkers installed decades ago to repel a naval attack. Near Yang’s fishing spot, soldiers once slept in dank tunnels, ready to spring into action against mainland invaders. Separated from Taiwan’s main island by 120 miles of ocean, Kinmen was the first line of defense.

Now, tourists wander through the empty tunnels and inspect loudspeakers that once blared Nationalist messages to the other shore. China has become a trading partner, not a military adversary, while still insisting on eventual reunification with the democratically governed island.

In Taiwan, the public discussion lately has centered on a proposed trade agreement with China that sparked a populist takeover of the national legislative building amid fears of growing too close to a former enemy.

“Ordinary people, we don’t ask for much — just peace, no war,” said Yang.

After retreating from the mainland in 1949, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists held on to Kinmen, surrounded by Communist Chinese territory on three sides. Formerly called Quemoy in English and also spelled Chinmen or Jinmen, the small island went from an agricultural backwater to a military base that for decades was the epicenter of cross-strait tensions.

It featured prominently in the 1960 presidential debates, with Richard Nixon arguing that the U.S. should come to Quemoy’s defense and John F. Kennedy asserting that only the main island was covered by a 1955 treaty.

Living in a war zone exacted a high toll on the local population, which today numbers about 120,000. Hundreds of civilians were killed in two major battles in 1949 and 1958, but residents on the main island were removed from the fighting.

At the height of the hostilities, soldiers jammed the streets of Jincheng and Shanwai, shopping at local businesses and generating extra cash for families who washed their laundry and heated water for their baths. Generations of young Taiwanese men did their compulsory military service on Kinmen, living amid rats and roaches in the maze of tunnels blasted into the island’s bedrock. Kinmen at one time had twice as many soldiers as locals.

As relations between Beijing and Taipei thawed, the Taiwanese military pulled back from Kinmen, which is about 10 miles across at its widest point. From a peak of nearly 100,000 soldiers in the 1950s, only about 3,000 are stationed here today. Many of the military tunnels have been abandoned or turned into tourist attractions.

Kinmen officials are scrambling to reinvent the island’s economy, seeking to increase exports of its famously strong kaoliang liquor. And they hope the former military installations will prove a draw for visitors, including mainland Chinese, interested in the contrast between then and now.

Li Wo-shih, Kinmen’s magistrate, makes the short hop to China a dozen times a year to talk trade and tourism. A deal is in the works for Kinmen to purchase some of its drinking water from the mainland.

Kinmen’s economic future lies with China and its vast supply of tourists and kaoliang customers, Li believes. Xiamen, a mainland city of 3.5 million, is a ferry ride away.

“We’ve been through war, but we don’t have any sadness or hate,” Li said. “The positive feelings between people come back really fast. We want to let the world understand that we no longer have war, and we also hope that the rest of the world can achieve that.”

In Kinmen’s farming villages, old cottages have been restored and turned into bed-and-breakfasts for visitors to experience traditional architecture and the rhythms of rural life. Crowds are sparse in the off-season, but tourism is the best hope to supplement agricultural incomes now that the soldiers are gone.

Chen Kun-chi, a retired schoolteacher, serves oyster omelets and oyster noodle soup from a stall in one of the refurbished villages in Kinmen’s northeast. Busloads of tourists arrive to admire the colorful wooden carvings on the red-tile-roofed houses.

“We didn’t know what day we might die. We’d eat a few bites of dinner, the bombs would come, and we’d have to hide,” Chen, 76, recalled of his childhood, when shells would rain down from China on odd-numbered days so civilians knew roughly when to find cover.

Having experienced warfare firsthand, older Kinmen residents want to avoid it at all costs. Kinmen’s proximity to Fujian province in China, along with a shared dialect and customs, means many residents feel an affinity for the mainland, intensified by the fact that they can now travel there freely. Some say they are not opposed to someday reunifying.

“I hope we can work together and not have war again,” Chen said. “We’re the same race. We can be like brothers.”

On the outskirts of Jincheng, the small town that is Kinmen’s capital, Tseng-dong Wu’s workshop blends the old and the new Kinmen.

As a group of tourists from Beijing looked on, Wu — known as Maestro Wu — picked up an artillery shell and began shaving it into a chef’s knife.

He is in no danger of running out of raw material. Decades of near-daily bombardments left hundreds of thousands of shells scattered across the countryside. The military steel, denser than most commercial steel, is perfect for making high-quality knives.

There are no restrictions on bringing kitchen knives into China in checked baggage, said a Chinese government spokesman in Los Angeles, and the visitors to Wu’s workshop return home with plenty of them.

“The Chinese tourists, they like the knives a lot,” Wu, 56, said. “It shows that the two sides have gone from war to peaceful cooperation.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.