Great Read: A brotherhood born of heroes in Normandy D-day landings

- Share via

CLEETHORPES, England — Some brothers you’re born with; others you choose.

War took one from Eric Gower, but it gave him dozens of others, bonded by a singular experience 70 years ago.

Patriotic and dutiful young men, they took part in the largest amphibious assault in history, against an enemy that held Europe in its grip. On June 6, 1944, wave after wave of Allied soldiers and equipment crashed onto the shores of Normandy, France, launching a massive operation that lasted more than two months and precipitated the defeat of Nazi Germany.

When the war was over, many of the fighters returned to “civvy street” here in Britain, to wives and kids and work, and a country eager to put the war behind it. Memories of the “Longest Day” receded, at least for those not involved.

“It was never brought up in conversation,” recalled Gower, 90. “If you said to somebody, ‘I did this in the war,’ they said, ‘I did this, and the sooner I forget about it, the better.’”

But some old soldiers, yearning for the comradeship they shared in the military campaign, decided to band together again. Thirty-six years after the end of World War II, four men gathered in this wind-swept corner of northern England to revive the spirit of D-day — and to keep alive the memory of those who didn’t make it back.

That seed grew into the Normandy Veterans Assn., which at its height had more than 100 branches across Britain and 15,000 members.

But unlike the enemy they battled on the beaches of northern France, time is a foe that cannot be vanquished.

With only a few hundred members still alive, the association has decided to dissolve. This fall, the group will hang up its banner for good, in a ceremony next to Westminster Abbey.

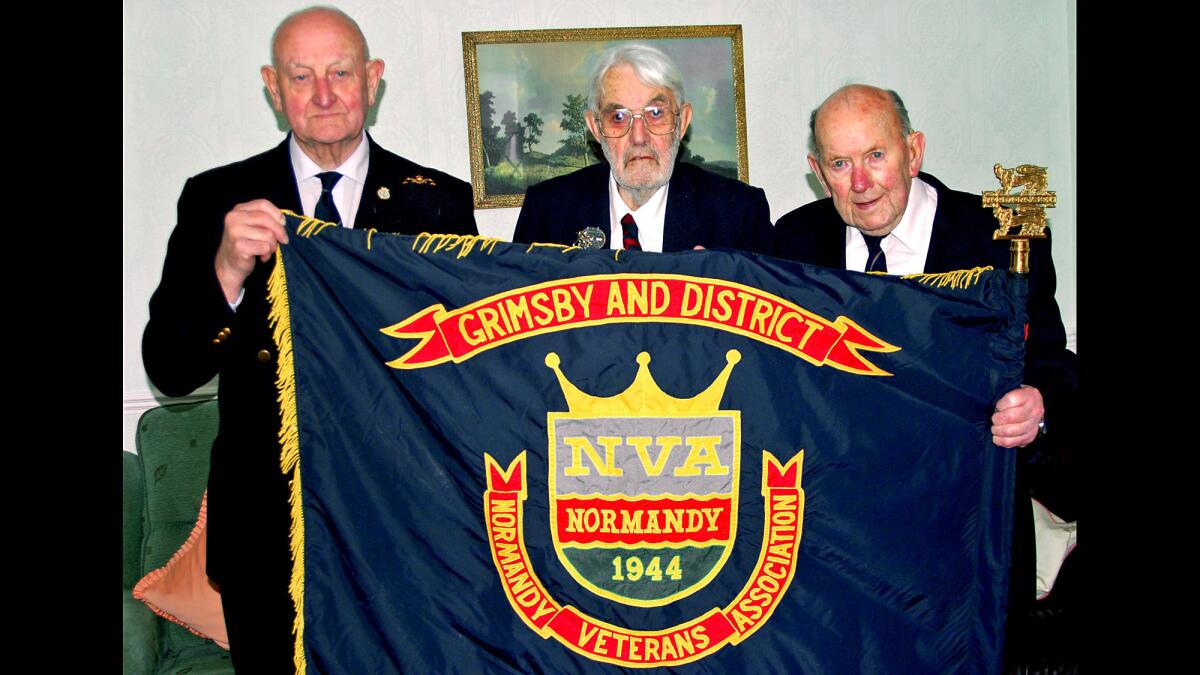

Gower and his “band of brothers” from Grimsby and District, No. 1 Branch — the founding chapter — will be there. The branch once boasted more than 400 members.

Five are left.

“It’s rather upsetting.... We’ve been together all these years, since 1981,” said Walter Marshall, who at 89 is almost as straight-backed as the young seaman he once was. “When they lay the national standard up in London, in Westminster, that will be it. It’ll all be finished.”

::

Marshall’s D-day service began before the invasion itself. In fact, he helped make it work.

Just 19, he was assigned to naval intelligence, which dropped him in Nazi-occupied, heavily fortified Normandy to reconnoiter enemy positions, minefields and potential obstacles a few days before the beach landings.

Dangers and discoveries lay everywhere. Once, a German convoy suddenly rumbled around a bend, forcing Marshall and his fellow spies to jump into a watery ditch to avoid detection.

A lake on their map turned out to be a flooded field in which the Germans had erected long poles with mines on top, to blow up the noiseless wooden gliders that the Allies used to deliver troops behind enemy lines.

On their last night of spying, weary and hungry, “we found a little copse of trees and we got in there, catnapping,” Marshall said. “I woke up in the morning, and I could smell coffee. Oooh, coffee! Only about 30 yards away was a German tank, and they were having breakfast.”

Marshall made it back to base in England, and filed his report on June 5, 1944.

That same night, he was sent off again, on an American destroyer full of British troops, cruising toward one of the Normandy landing spots.

By then, Gower, too, was steaming across the English Channel.

A former butcher’s apprentice who had been drafted two years before, he knew he was to be part of an invasion force to help liberate continental Europe. But neither he nor his fellow recruits had any idea when or where it would occur.

A few weeks before the force shipped out, King George VI made a royal inspection of Gower’s brigade, in southern England. Afterward, officers put the camp in lockdown, to prevent any information from leaking from the soldiers’ briefings.

Aboard his boat, anchored in the darkness off the Normandy coast, Gower still had no sense of the scale of what they were about to attempt.

“It wasn’t until daylight of the morning of June 6, maybe half past 5 in the morning, we looked around, and by then, the vessels … had come from all directions,” he recalled. “It wasn’t until then you realized how big it was. It was just unbelievable.”

::

Allied forces landed 156,000 troops that day, most of them by sea but some by air. More than 5,000 ships and 11,000 aircraft were deployed. The United States contributed 73,000 troops, Britain 62,000 and Canada 21,000.

Though meticulously planned, the operation inevitably ran into problems. In weather so blustery it had threatened to delay the assault, troops and materiel pouring ashore couldn’t clear off as fast as expected to make way for the next batch. Gower, in the second wave to hit Sword Beach, stormed ashore about 10 a.m. but couldn’t punch farther inland until early afternoon.

All the while, gunfire whizzed past and artillery keened overhead, in a thunderous, unrelenting roar that Gower says was the beginning of the hearing loss he suffers from today. Tanks lumbered everywhere around them.

“I didn’t expect it to be easy. Nobody did,” said Marshall, who remained on board ship off Gold Beach, helping to coordinate the landings. “But it was more chaotic than I thought it would be.”

Then there were the corpses, thick in the sea and on the sand. Comrades who had stood shoulder to shoulder hours earlier now lay dead, blocking the way of the men who came behind them.

“All I remember was how many bodies I saw in the water. It was terrible,” Marshall said. “When I saw these lads going ashore, after lunchtime, pushing their way through the bodies, it was heartbreaking. The landing craft were trying to get as many of the bodies out of the water as possible, but they couldn’t.”

By day’s end, Allied dead exceeded 4,000, according to recent research that puts the figure higher than the long-standing estimate of 2,500. The number of German casualties is unknown.

The Battle of Normandy, which D-day inaugurated, raged for more than two months. Gower fought his way inland and, while still in France, learned in a letter from his mother that his brother had been killed in action in the Netherlands.

::

Henry Draper joined the battle in July, landing on Juno Beach, which was securely in Allied hands. Although he saw action throughout Normandy, on artillery duty, he credits men like Gower and Marshall with clearing the path before him, at great cost, on June 6.

“If these lads hadn’t done what they did and thousands of people got killed, I wouldn’t be here today,” Draper said.

Draper served for many years as auditor of the Grimsby and District, No. 1 Branch. For years, the branch has held meetings once a month here in Cleethorpes, next to Grimsby, and thrown occasional dinner and dance parties where the wine and memories flowed.

When one member’s home was flooded, fellow vets sprang to his aid. And when Ken Collins, of the original gang of four who convened the very first meeting in 1981, journeyed to London for eye surgery, a quick phone call to the branch down there brought visitors to his hospital bedside within hours.

The association has helped veterans attend the 40th, 50th and 60th anniversary commemorations in Normandy. In 2004, for the 60th, a sizable contingent of D-day participants was still alive, including about 10,000 members of the association, said George Batts, the group’s national secretary.

But the last 10 years have decimated the ranks as stalwarts neared or entered their 90s. The number is now down to about 600, fewer than half of whom will attend the 70th anniversary events on Sword Beach this Friday, alongside such dignitaries as President Obama and Queen Elizabeth II. (Some D-day vets who aren’t members of the association will also attend.)

For those left, eyesight, hearing, joints and memories have all begun to fail. Even Draper, who attended the three previous decennial celebrations, has decided to skip the 70th anniversary, confessing that earlier this year, at 93, “I began to feel me age.

“I shall be there in spirit,” Draper declared.

On Sunday, Draper’s 94th birthday, the Grimsby chapter will hang up its banner in the local church. On Nov. 5, the Grimsby and District veterans will gather for their last formal meeting, perhaps with eyes misted over not just by age.

But Draper, Gower and Marshall are sure they’ll continue to see one another and the two other remaining members, George Artis and Alf Duncan. There’s no one else in Grimsby who knows what they went through. No one who can honor, in quite the same way, the comrades who weren’t as lucky as they were.

“All those lads going up the beaches — I’ll never forget the courage of those lads,” Marshall said. “There was a hell of a lot of heroism that will never be known. Every beachhead gave their all.

“I wouldn’t have missed it,” he said. “To go through that experience and to come through the other side, it’s a thing that you can look back on and think, ‘I’ve come through it all.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.