Guatemala amnesty bill stirs fears of impunity and revenge of ex-military

- Share via

Legislation that would grant amnesty to anyone convicted or accused of human rights violations during Guatemala’s long-running civil war has raised fears that dozens of perpetrators of forced disappearance, torture and sexual violence could soon walk free.

Backed by military elites and their allies, including members of the party of President Jimmy Morales, the proposed law passed the first of three congressional readings in January. A second discussion was scheduled for Wednesday.

If enacted, the bill would mandate the release within 24 hours of dozens of officials and military officers convicted of crimes related to the 36-year armed conflict and a halt to ongoing or new investigations of internationally recognized rights violations connected to the civil war.

During the fighting that lasted from 1960 to 1996 between leftists and the government, about 200,000 people were killed. Among the bloody actions was a military campaign against indigenous communities considered allies of Marxist guerrillas fighting the government.

A United Nations-backed truth commission in 1999 found security forces guilty of “multiple acts of savagery” and genocide against Maya communities, and held the government accountable for more than 90% of the killings, disappearances and other human rights violations.

For more than a decade, the United Nations-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala has helped strengthen the capacity and autonomy of the attorney general’s office and the judiciary in Guatemala, which was critical to the progress made in war crimes prosecutions in recent years, wrote Jo-Marie Burt, a Latin American Studies expert at George Mason University, in an email.

Verdicts between 2008 and 2018 resulted in more than 30 convictions of military officials and state actors, as well as one of a guerrilla fighter, according to Burt. That included the 2013 sentencing of former dictator Gen. Efrain Rios Montt for genocide and crimes against humanity. (His conviction was later overturned and he died while he was being retried last year.)

But those backing this bill have found support in the party of Morales, who was elected in 2015. They have recently stood by Morales in his clashes with institutions tasked with investigating crime and corruption.

“It’s an attempt to undermine that,” Eric Olson, an expert on Central America at the Seattle International Foundation, said of the bill’s supporters. “They’re under threat by the justice system in Guatemala.”

In January, the government said it was expelling the U.N.-backed commission, known by its Spanish acronym as CICIG, despite rulings from the country’s highest court to allow commission members to enter the country. The CICIG had brought fraud charges against Morales’ brother and his son, and had also opened an investigation into Morales related to illegal campaign donations.

“The sectors that have been hurt by the justice system are pushing back,” said Viviana Krsticevic, the executive director of the Center for Justice and International Law, a Latin American human rights organization. “The government has been willing to protect its social and economic base even at the cost of challenging international agreements and principles.”

Claudia Paz y Paz, a former attorney general of Guatemala during the prosecution of Rios Montt, said that previous attempts to gain amnesty have never advanced this far. The president, however, she said, has many supporters who have been implicated in human rights crimes who favor the legislation.

“They are committed to returning to the past and guaranteeing impunity, whether it’s for crimes from the war or cases of corruption,” she said.

Olson, who works at the Washington office of Seattle International, said that legislators may be empowered by what they see as support from the Trump administration. Although the U.S. released a statement expressing concern about the law, it did not strongly defend the CICIG against attacks from Morales’ government, which last May moved its embassy to Jerusalem shortly following the U.S.

After Morales announced his plan to shut down the commission, U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo sent a tweet praising Guatemala’s relationship with Washington and thanking it for its “efforts in counter-narcotics and security.”

“I think there’s this perception among these circles in Guatemala that they won’t have a heavy price to pay if they move in this direction,” said Olson. “There’s a perception that they have succeeded in weakening the CICIG, and there’s a perception that the U.S. has been less than vigorous and hard on them.”

Juan Francisco Soto, the executive director of the Center for Human Rights Legal Action in Guatemala, said that reconciliation after the war means “understanding that justice guarantees that these things won’t happen again in Guatemala.”

“These are processes that have taken years, and victims have pushed them forward,” he said. “It mocks victims after so much fight.”

Ana Lucrecia Molina Theissen spent decades trying to obtain justice for her sister’s torture and her 14-year-old brother’s forced disappearance in 1981. Marco Antonio was abducted after his sister, an activist, escaped from a military base where she had been sexually assaulted and tortured. In 2004, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that Guatemala was responsible for the forced disappearance, and last May, Guatemala convicted four military officers involved in either or both cases.

“In many ways, this was a situation that we expected because the people and sectors that support [the bill] aren’t passive — they have a lot of power,” she said. “This is a return to the fight, as well as the realization that justice in Guatemala is still very fragile…. We’ve spent 36 years suffering, and seeing it [justice] fall in an illegitimate way turns us into victims again.”

The bill, introduced in November 2017, needs 80 votes from Congress’ 158 legislators to pass. On Feb. 20, those in opposition walked out of the session so that its supporters fell short of the quorum needed to discuss the bill.

The proposal would reform Guatemala’s 1996 National Reconciliation Law, which permits amnesty for crimes that could be considered political but excludes amnesty for international abuses like genocide, torture and other crimes against humanity. The proposal claims that the greater number of charges against military officials and state agents compared with guerrillas points toward “judicial harassment of only one side of the conflict, the military,” and says there was no genocide during the war.

Fernando Linares Beltranena, the congressman who introduced the bill, holds that people cannot be convicted for crimes that were not stipulated in Guatemala’s penal code at the time.

“All this law is doing is giving life to what was approved but not implemented 23 years ago,” said Beltranena. “It was better to have an amnesty than to have bloodshed. But we got an unequal, one-sided prosecution by judges and prosecuting attorneys who sided with one faction of the conflict and mostly those who are being prosecuted are military.”

The bill has received pushback from the U.N., the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and other human rights groups that say it violates Guatemala’s international obligations to investigate human rights violations.

The Inter-American Court has previously considered amnesty laws passed by Latin American countries invalid, and if the law passes, Krsticevic said, she expects the court to declare it void. Its decisions are considered legally binding by countries that have accepted its jurisdiction, such as Guatemala. In 2001, for example, it determined that the amnesty legislation Peru adopted in 1995 to shield those implicated in human rights violations did not have legal effect.

Congresswoman Sandra Moran, who opposes the bill, has expressed concern that “it’s only a matter of time” until it passes. Many worry those convicted would seek retaliation if released.

“There is a lot of fear about the risk to the victims, the prosecutors, and the people that gave testimony or declarations to help shine light on the truth during the trials,” she said.

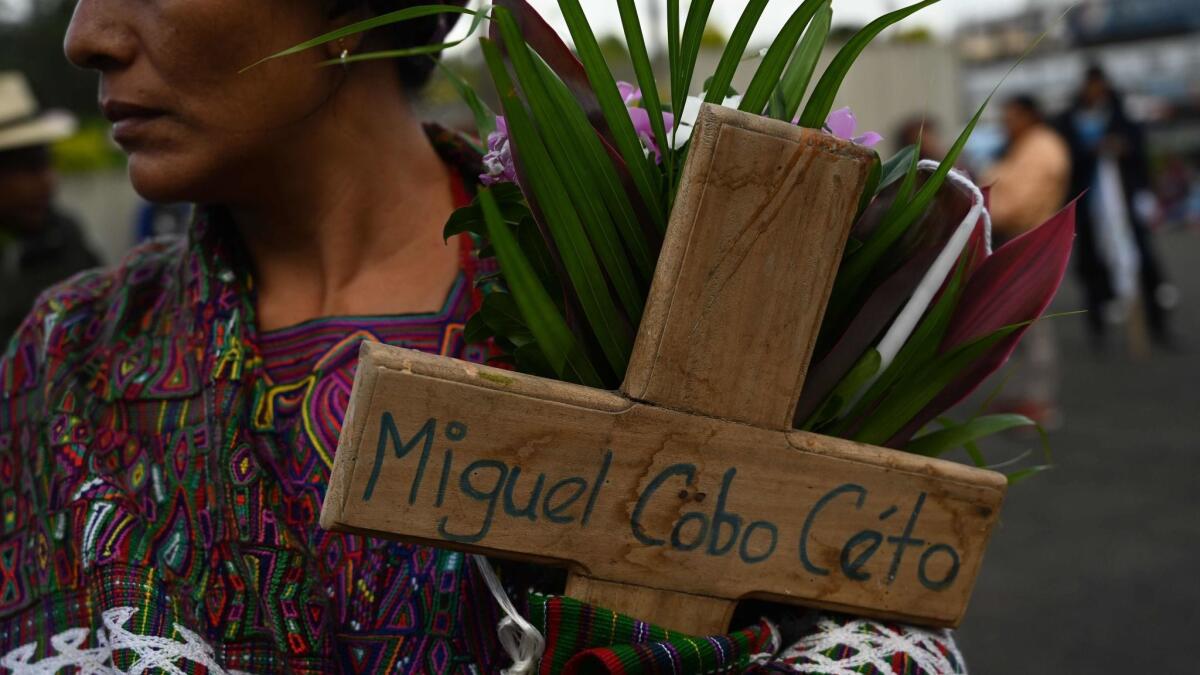

The mounting tension coincided with Monday’s “Day of Dignity” for the victims of the internal armed conflict — the anniversary of the 1999 U.N.-commissioned report on the war. This year, the amnesty bill was at the forefront of protests by human rights and victims groups.

Edwin Canil, the leader of a victims group, joined hundreds of people who marched from the Supreme Court to the Congress. Many, he said, came from communities that bore the brunt of the violence during the war, and held handmade signs with photos of the disappeared.

Canil was 6 years old when he survived a massacre in Guatemala’s Ixcan region that killed members of his family.

“There’s been an enormous setback to democracy in the country,” he said. “It’s outrageous. Once again, we feel completely unprotected — as we felt during the armed conflict.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.