As Mexico debates giving the military more power, a judge asks why soldiers gunned down 22 people

- Share via

Reporting from Mexico City — As Mexican lawmakers debate expanding the role of the military in the country’s drug war, a judge has ordered a new probe into whether army commanders ordered soldiers to shoot 22 people in a 2014 incident described by human rights advocates as an extrajudicial massacre.

The federal judge, whose July 31 ruling became public this week, said the federal attorney general’s office failed to fully investigate a military order issued before the killing that instructed soldiers to “shoot down criminals in hours of darkness.”

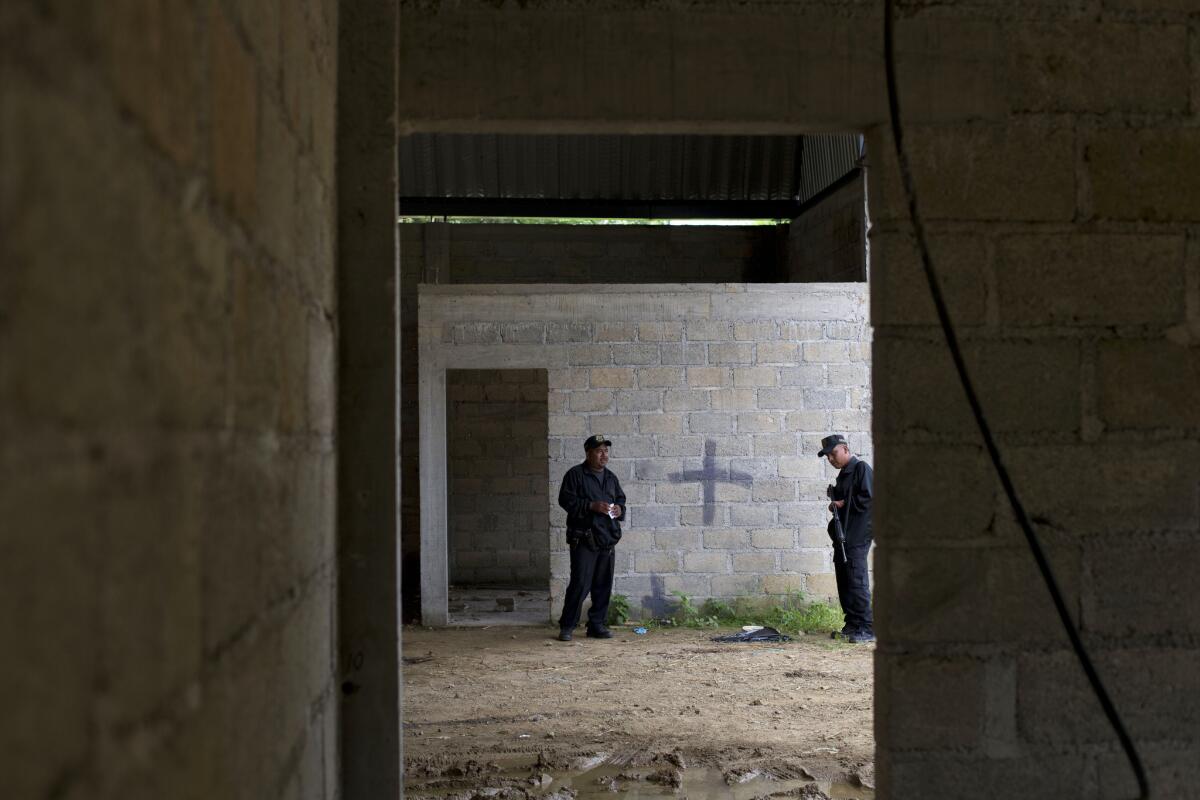

Initially, the army described the shooting deaths at a warehouse in Tlatlaya, about 100 miles southwest of Mexico City, as the result of a fierce gun battle with an armed gang. But news reports and the testimony of survivors later suggested that the army had executed at least a dozen people at point blank range, including several who had already surrendered to an army patrol or who lay wounded.

After the government’s own human rights agency charged that as many as 15 of the suspects were executed, seven soldiers were charged with homicide in connection to the case. They were acquitted by a military court, and a judge in a civilian court threw out the charges against all of them, citing insufficient evidence.

This month’s ruling was made in a complaint filed by one of three women who survived the incident and later claimed that agents from the state prosecutor’s office had tortured them into corroborating the army’s version of events.

The judge said the attorney general’s office has failed to diligently conduct an “investigation into the facts or the orders issued to military elements through the chain of command.”

In a statement, the human rights organization Centro Prodh said the ruling highlighted the ineffectiveness of Mexico’s justice system.

“The impunity… shows the structural flaws in the administration of justice in Mexico, especially when public servants are involved,” the statement said. It urged Mexico’s members of congress to vote against proposed legislation, called the Law on Internal Security, that seeks to expand the military’s presence in public security.

For a decade now, tens of thousands of Mexican soldiers and naval officers have been embedded in local communities as part of the government’s strategy to fight drug cartels, in part because military officers tend to be regarded as less corrupt than local and state police forces, some of whom collaborate with the cartels.

Human rights advocates say that instead of solidifying the presence of the armed forces in Mexican communities, lawmakers should instead focus on initiatives to strengthen and professionalize Mexico’s civilian police forces. They point to the military’s role in grave rights violations, including documented cases of soldiers engaging in torture and carrying out execution-style killings.

Between January 2012 and August 2016, there were 5,541 complaints of human rights violations against the armed forces registered with the National Human Rights Commission. Only about 6% of those complaints, which included allegations of homicide, torture and rape, resulted in criminal trials.

Beyond accusations of rights abuses, rights advocates and some members of Mexico’s political opposition point out that the military has failed to effectively reduce violence and organized criminal activity.

The federal forces have executed a “kingpin strategy” that targets cartel leaders. One by one, powerful drug lords, including Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, have been taken into custody or killed. Although some security analysts say federal forces helped stop Mexico from becoming a narco state, the strategy also unleashed a wave of violence as would-be kingpins fought for control of the cartels.

Mexico is now on track to record more homicides in 2017 than in any year since authorities began publishing murder statistics 20 years ago.

Cecilia Sanchez in the Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

Twitter: @katelinthicum

ALSO

Mexico enters new NAFTA negotiations with delicate task: give President Trump a ‘win’ but do no harm

What does it take to secure a border? Lessons from the wall dividing San Diego and Tijuana

What it’s like to report in one of the world’s deadliest places for journalists

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.