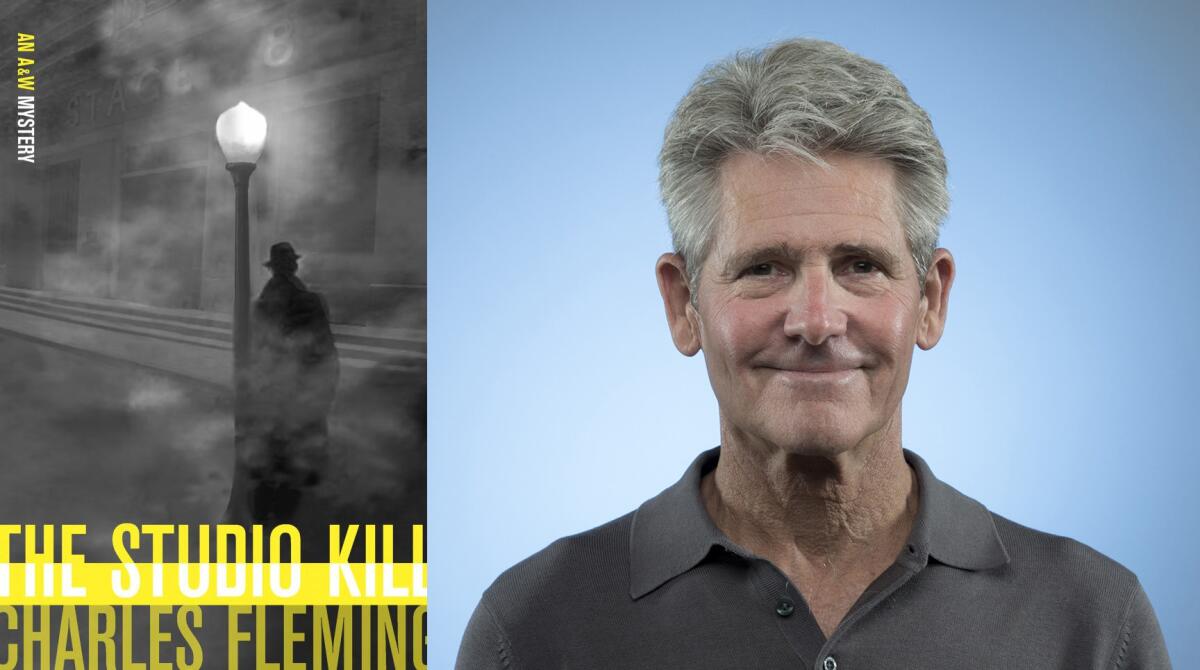

Q&A: Charles Fleming on vintage Hollywood and his novel ‘The Studio Kill’

- Share via

Charles Fleming’s “Secret Stairs: A Walking Guide to the Historic Staircases of Los Angeles” is a perennial bestseller in Los Angeles’ bookstores. The L.A. Times columnist is also a mystery writer who has just published his third hard-boiled novel -- and it’s the first set in Los Angeles.

“The Studio Kill” (Asahina & Wallace: $16) depicts a world of studio fixers, tabloid journalists, and gangsters during Hollywood’s Golden Age. Set during the Red Scare, the story follows John McClellan, a “security officer” for a major film studio as he investigates the murder of a film director’s wife. Along the way, McClellan encounters self-aggrandizing politicians on the hunt for Communists in screenland, thuggish gamblers, and lethal studio politics.

Fleming fills the book with historic details and snappy dialogue, making it a delightful read. The story plays like a noir movie in your head: It’s “Laura” crossed with “The Last Tycoon.” We reached him via e-mail to talk about the book.

What does a murder mystery, set during Hollywood’s red-baiting postwar years, have to teach us now?

I had been eager for some time to return to the series of West Coast noir books that I began with the novels “The Ivory Coast” and “After Havana,” and I’d long been intrigued by how Hollywood people handled the Red Scare of the late 40s and early 50s -- some so bravely, and others with such craven cowardice. American citizens were terrified of an enemy they didn’t know and couldn’t see, and in their fear became willing to forfeit their civil and human rights, much as we, since the events of September 11, in our fear of terrorism, have been willing to forfeit many of ours.

What attracted you to the story of a studio fixer? Is John McClellan based on a real figure in Hollywood history?

The major Hollywood movie studios all employed private police forces, many until the late 1950s, who stepped in -- and usually got there before the Los Angeles, Beverly Hills or other police forces did -- when a star got drunk, got in a fight, crashed a car or attempted suicide. So, there are many individual precedents for a studio cop of this kind, some of whom, working for MGM or Paramount, were legendary in their time. In “After Havana” I invented the specific character of John McClellan for a specific and relatively unimportant scene. He came on, did his job, and went away. But I found that, having invented and then dispensed with him, I could not forget him. I decided to make him the central figure in his own Hollywood story with “The Studio Kill.” And, I hope, several sequels.

One character lives in the Art Deco treasure the Montecito on Franklin Avenue in Hollywood. Have you been inside? Was it really a residence hotel with just one phone for its tenants?

I moved to Hollywood in 1978 and lived in a beat old building a couple of blocks away from the faded but still glamorous Montecito, which stands to this day as a beacon to those bygone days. I’m not certain that it had a phone in the lobby, but a lot of Hollywood apartments in the 1940s didn’t have phones in all the rooms.

The story is filled with detail like “A dresser drawer was filled with lingerie from Jewel Park and Bullock’s Wilshire. A second drawer held gossamer blouses from I. Magnin and Lanz of Salzburg.” How much research did you do and where did you get your info? What is Jewel Park and what does it say about the character, Claire Korman, who possessed the lingerie?

I did an enormous amount of research, as you must for a book of historical fiction, to create a heightened sense of reality for “The Studio Kill,” trying to be as accurate as possible about the clothes that Hollywood men and women were wearing, the cars they were driving, the cigarette brands they were smoking, the booze they were drinking, and the restaurants and nightclubs they were patronizing. For a woman like Claire Korman, drawers full of clothing made by Lanz of Salzburg, and purchased at Jewel Park, connote a woman of means, wealth and taste. Which, given the circumstances in which McClellan finds them, did not prevent her from coming to a very unhappy end.

The character of Danny Vine is fascinating. Is he an accurate portrait of a columnist for a newspaper of the era? How do you compare journalistic coverage of Hollywood in 1947 and now?

Danny Vine deserves his own book, and may get one. He’s cocky, and clever, and just barely this side of being completely corrupt and he took me by surprise. He sprang to life and became irrepressible, and got a lot more ink in “The Studio Kill” than I’d originally intended. In terms of his work as a reporter, he’s fashioned on a pool of highly competitive Hollywood columnists who were fighting for Hollywood stories at the time -- fighting the studios, fighting the cops and fighting each other. The dirt-digging and mud-slinging were shocking, and the competition was merciless, much as it is today with TMZ, the marauding paparazzi, and the trench warfare being waged by Deadline Hollywood, The Wrap, The Hollywood Reporter and Variety. Having covered the entertainment industry for as long as I did, though, I can say with some confidence that today’s reporters are at least trying to get the facts straight. I’m not sure that was always true with the columnists of Hollywood in the 1940s, who were willing to print almost anything -- negative or positive -- to boost their circulations and improve their standings with the studio bosses.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.