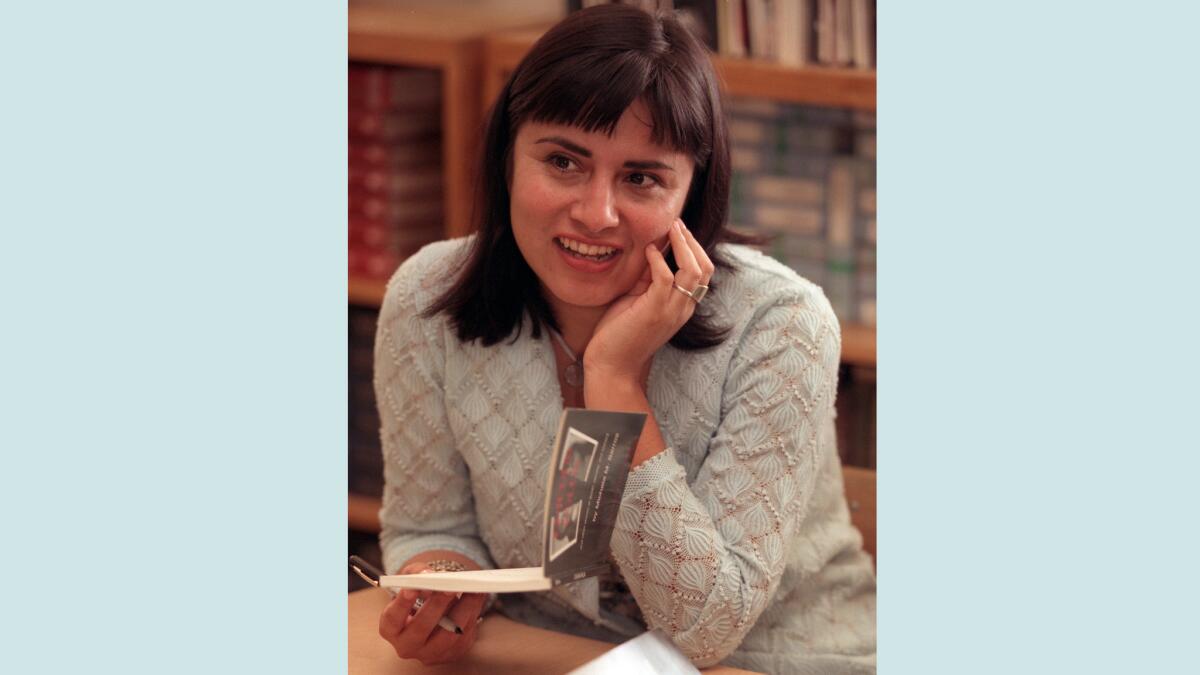

Writer Michele Serros dies at 48

Author Michele Serros, known for her poetry and the books “Chicana Falsa and Other Stories of Death, Identity and Oxnard” and “How to Be a Chicana Role Model” died Jan 4 at 48 from cancer.

- Share via

I used to know Michele Serros — who died of cancer Sunday at her home in Berkeley at the age of 48 — a little bit. In the mid-1990s she and I, along with a bunch of other people, helped launch PEN in the Classroom, a program to put writers together with under-served students in Los Angeles-area high schools.

For Serros this was an unlikely homecoming. Growing up in Oxnard, she found herself on the outside looking in. “We never said we lived in Oxnard,” she once explained of her family. “We always said we lived between Malibu and Santa Barbara.”

What makes such a line so telling is that it sets up the tensions and the oppositions, as well as the sharp sense of humor, that occupied the center of Serros’ work. There’s a reason, after all, that her first book — published in 1994, while she was a UCLA undergraduate — was called “Chicana Falsa and Other Stories of Death, Identity and Oxnard,” a titled inspired by a high school classmate called La Letty, who “had a strong definition of what a Chicana was.”

In a 1997 Los Angeles Times profile, Serros explained the conflict: “Here I was in school thinking maybe I’d go to college and become a writer. My Spanish was horrible, I wore Vans to school and La Letty was like ‘What a Chicana falsa you are.’ ”

More to the point, Serros was writing about a different kind of Chicana experience. She was a pure product of Southern California, not unlike poets such as David Trinidad or Michele T. Clinton, influenced by pop culture as much as by a more traditional sense of heritage. “I grew up fourth-generation Californian,” she once explained. “To me, all my experiences — the beach, the malls, avocados — very Californian. I happen to be Chicana.”

Indeed, it was Judy Blume who inspired her to be a writer, after Serros, then 11, wrote to the author about the emotions stirred up by her parents’ divorce. Blume wrote back, in a letter Serros kept near her computer throughout her writing life. “Divorce can be painful,” the YA author acknowledged. “You may want to keep a journal and write down what you are thinking and feeling.”

Throughout the 1990s Serros was a staple on the Los Angeles spoken word scene. She once organized a publication party in the form of a quinceañera, all the writers performing in festive gowns, and in 1994 she was chosen as one of 12 poets to tour with Lollapalooza.

Two years later “Chicana Falsa,” which had fallen out of print, appeared on CD. It would later be reissued by Riverhead, along with a follow-up, “How to Be a Chicana Role Model,” which came out in 2000. She also spent a year as a staff writer on “The George Lopez Show.”

Most recently, Serros published two YA novels, “Honey Blonde Chica” and “¡Scandalosa!”; these books zeroed in on upper-middle-class Latina life.

“I grew up reading a lot of young adult novels,” she told NPR in 2006.” And being an author and speaker and going into middle schools and high schools, I was seeing a lot of the same books that I read and they followed a similar theme. That’s a theme I call the three Bs. It was always about barrios, borders and bodegas, and I wanted to present a different type of life, a life that truly goes on that we don’t always see in the mainstream media.”

Serros did that. She wrote out of her own experience, her own identity, shying away from none of it, revealing all. She was funny and discomforting — often in the space of the same piece.

“My cancer?” she wrote in an essay last July on the Huffington Post. “I didn’t recall co-signing for such ownership. Once receiving the news that my status had advanced to Stage 4, I woke up every morning to a day consisting of nonstop fear and crying. I would have pulled out my hair completely from all the panic-riddled anxiety I endured, but I needed to keep any and all of it — for as long as I could. Suddenly, losing my hair seemed more traumatic than having cancer.”

That’s some gutsy writing, work that looks into the maw of the abyss and yet retains a sense of humor. It’s not dying that’s important, such a passage tells us, but rather how we live.

“Losing an artist is losing language and the unique way in which we hear stories and see ourselves in the world,” playwright and performance artist Luis Alfaro wrote in a moving tribute to Serros on his Facebook page. “The immensity of such silence is what I am reeling with right now.”

Twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.