James Sallis’ noir outlook in ‘The Killer Is Dying’ and ‘Drive’

- Share via

Reporting from Phoenix — James Sallis lives in a place that really shouldn’t exist. The city sits in the middle of “an incredibly forbidding desert,” where on this day the temperature will reach 112 degrees. Like Los Angeles, decades ago it became too big for its local water supply. It’s a place of migrants, and of rootlessness. It feels as permanent as a trailer park.

Which makes Phoenix the perfect setting for Sallis’ dark new novel, “The Killer Is Dying,” (Walker: 233 pp., $23) a sparse, noir tale of a sick and slowly dying hit man, the homicide cop trying to run him to ground and a resourceful teenager carving out an improbable life after both parents abandon him.

“There’s something very intriguing about this place,” says Sallis, an Arkansas native who lived in New York, Boston, London and a handful of other places before settling here in 1995. “The book is really about people who are cut off, either for personal reasons or familial reasons, or social reasons, whatever, they’re cut off from society. This artificial town in this desert, without bringing it up to the surface of the story, really seemed to work for it.”

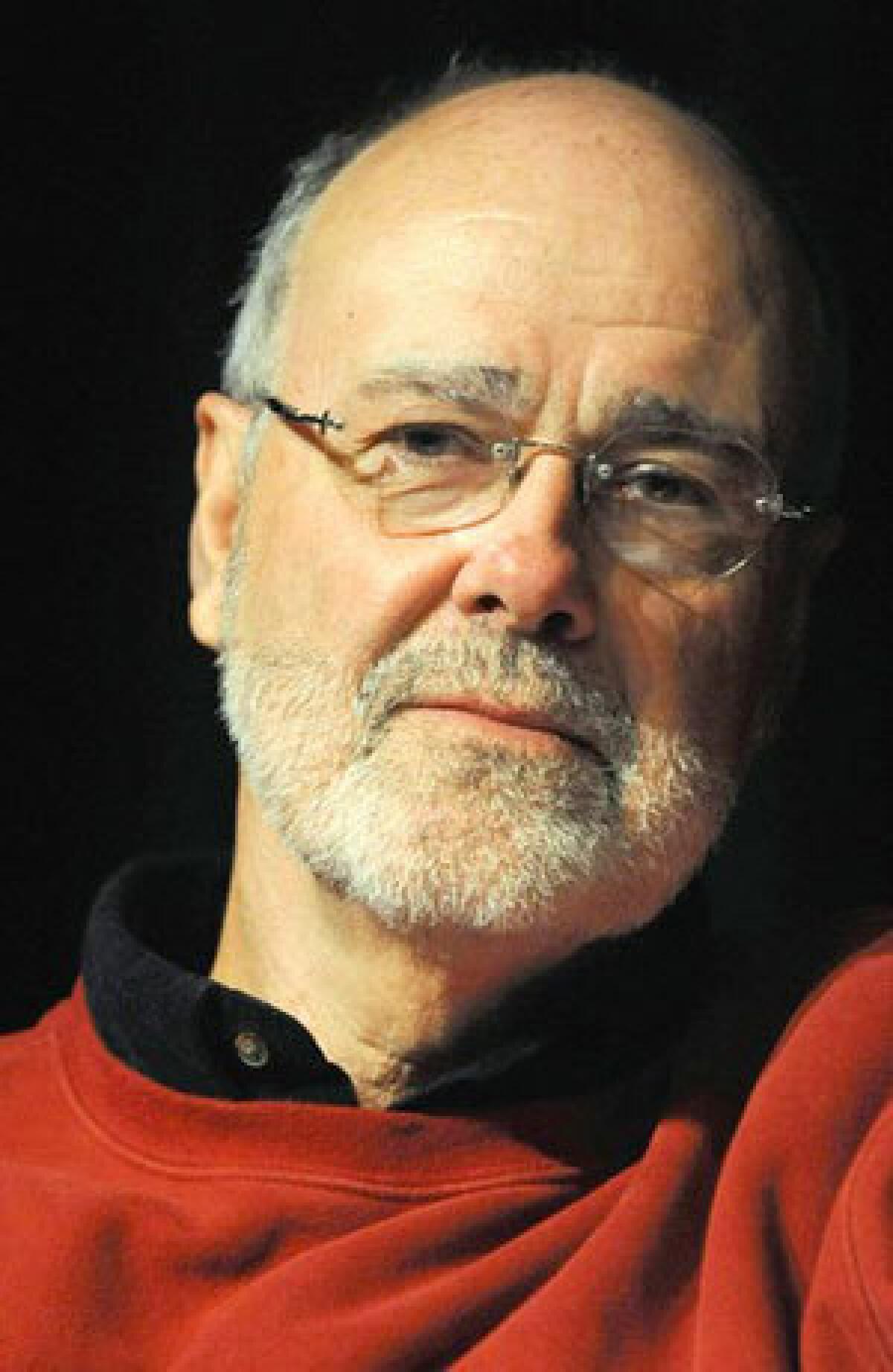

At age 66, Sallis is balding, with gray hair and beard, and in his wire-rim glasses he looks a bit like Elmore Leonard. Arkansas still drips from his voice, and he finds a dark humor in most things, including noir and crime novels and movies.

“I like edgy stuff,” he says. “My attraction to crime fiction is that it puts people in strange situations. Their relationship with the world becomes much, much stronger when you see them in extreme situations, and that doesn’t mean that you can’t find a lot of humor there.”

Sallis worked for decades outside the literary mainstream, producing more than two dozen books, including the six-volume Lew Griffin detective series, collected profiles of blues guitarists and a biography of Chester Himes, who set the benchmark for gritty portrayals of black life in America from the Depression years through the postwar era. Sallis also has translated poetry from Spanish, French and Russian.

“I studied Russian formally for many years, chiefly because I wanted to read the poetry in the original,” he says. “Most of it now, alas, is gone. I also studied Spanish for a while with a native speaker, again to be able to make my way through poetry.”

While wide recognition has been elusive, that could change this fall. Sallis’ new novel is out a few weeks ahead of the Sept. 16 release of “Drive,” the Nicolas Winding Refn-directed movie adapted from Sallis’ 2005 novel of the same name, which is being republished as a tie-in. The film premiered in June at the Los Angeles Film Festival, picking up strong praise from reviewers.

A hit movie would be nice, Sallis says. His books have been optioned before, but “Drive” is the first to make it to screen. Sallis’ involvement ended with selling the rights, and he first saw the production at the Los Angeles premiere. He found it “astonishing.”

Refn “said he wanted it to be what the book was, and he did, with some changes,” Sallis says. “The spirit of the book is right up there on the screen. It’s romantic. It’s sweet. It’s incredibly violent, almost too violent for me in some places. But the violence is real, it happens, there’s no dwelling on it. You believe it.”

“Drive” and “The Killer Is Dying” both focus on improbable characters. In “Drive,” the main figure is an unnamed Hollywood stunt man (played by Ryan Gosling) who moonlights as a contract getaway driver for robbers, and who eventually runs afoul of his clients. In “The Killer Is Dying,” the center stage is shared by Christian, the dying killer of the title whose real identity remains murky; homicide Det. Dale Sayles, whose wife is slowly dying of cancer; and Jimmie, the boy who fools the world into thinking his parents are still managing his life, when is reality they have run off.

The characters’ lives intersect in odd ways. Someone tries to murder the killer’s target before he gets there, sending the killer off on a search for the interloper. Jimmie seems to share the killer’s dreams. Sayles and his partner are investigating the attempted killing, which brings them in contact with both of the murderers. Resolutions are implied, the plot propelled by finely sanded prose that suggests more often than states.

Sallis didn’t set out to be a novelist. Growing up in the Mississippi River town of Helena, Ark., Sallis at first dreamed of becoming a composer of classical music, which he studied downriver at Tulane University in New Orleans. Then he married and decided he needed to find a way to make a living. “So I thought I was going to be a journalist. That didn’t last very long. I wanted to write about stuff nobody in the journalism school thought was interesting, the arts, books, music.”

It was the mid-1960s. Sallis dropped out of school and turned his pen to science fiction, selling a 6,000-word story for $300. “I thought I was in high cotton,” Sallis says, adding that he thought he was on his way to financial stability. Things didn’t work out that way.

“I did survive writing short stories, for quite some time,” he says. “I didn’t survive well. I lived very, very simply. Garage apartments got to know me really well. Sneaking out of apartments in the dead of night. But I did it for a long, long time. And then finally the short story market kinda collapsed.”

He returned to journalism, writing about music for guitar-oriented magazines (he plays guitar, dobro and other stringed instruments in the Three-Legged Dog string band); book reviews for the Los Angeles Times and the Boston Globe, among others. He began moving toward more literary science fiction — the terrain Jonathan Lethem has worked in more recently. Eventually Sallis became a pediatric respiratory therapist and a writing instructor at Phoenix College, a two-year school near his home, to cover bills that his writing career couldn’t.

“The Killer is Dying,” at fewer than 240 pages, is longer than most Sallis novels, and his brevity forms a running joke among his writing students.

“Someone will ask, do you still write short stories? And the other will say, yes, but he publishes them as novels,” Sallis says. “What I tell my students is you need to leave space. You need to let the story breathe. Don’t overexplain. Let the reader join in the story.”

Drawing from Anton Chekhov, “who wanted the reader to be a collaborator,” Sallis believes the fewer details he offers, the more the reader supplies in his or her mind and thus becomes more deeply drawn into the story itself.

“I think my writing has gotten sparser and sparser as I find I can get the effect I want much easier now with fewer words than I could before. One of the early reviews of the new novel said something like, ‘Sallis’ latest prose poem.’ And that’s kind of the way I think of them.”

Martelle is the author of “The Fear Within: Spies, Commies, and American Democracy on Trial.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.