Taking a businesslike approach to social woes

- Share via

Like many revolutionary manifestoes, “The Solution Revolution” seeks the overthrow of government as we know it.

But for authors William Eggers and Paul Macmillan — who work in public-sector practice at Deloitte — this is a revolution very much in the interests of business, not against it.

The book, “The Solution Revolution: How Business, Government and Social Enterprises Are Teaming Up to Solve Society’s Toughest Problems,” is a compendium of case studies of entrepreneurial individuals and organizations taking on some of the most intractable social problems.

The authors argue that “private enterprise for public gain no longer need be an oxymoron” and that social enterprises can “backfill public services.” The book is published by Harvard Business Review Press.

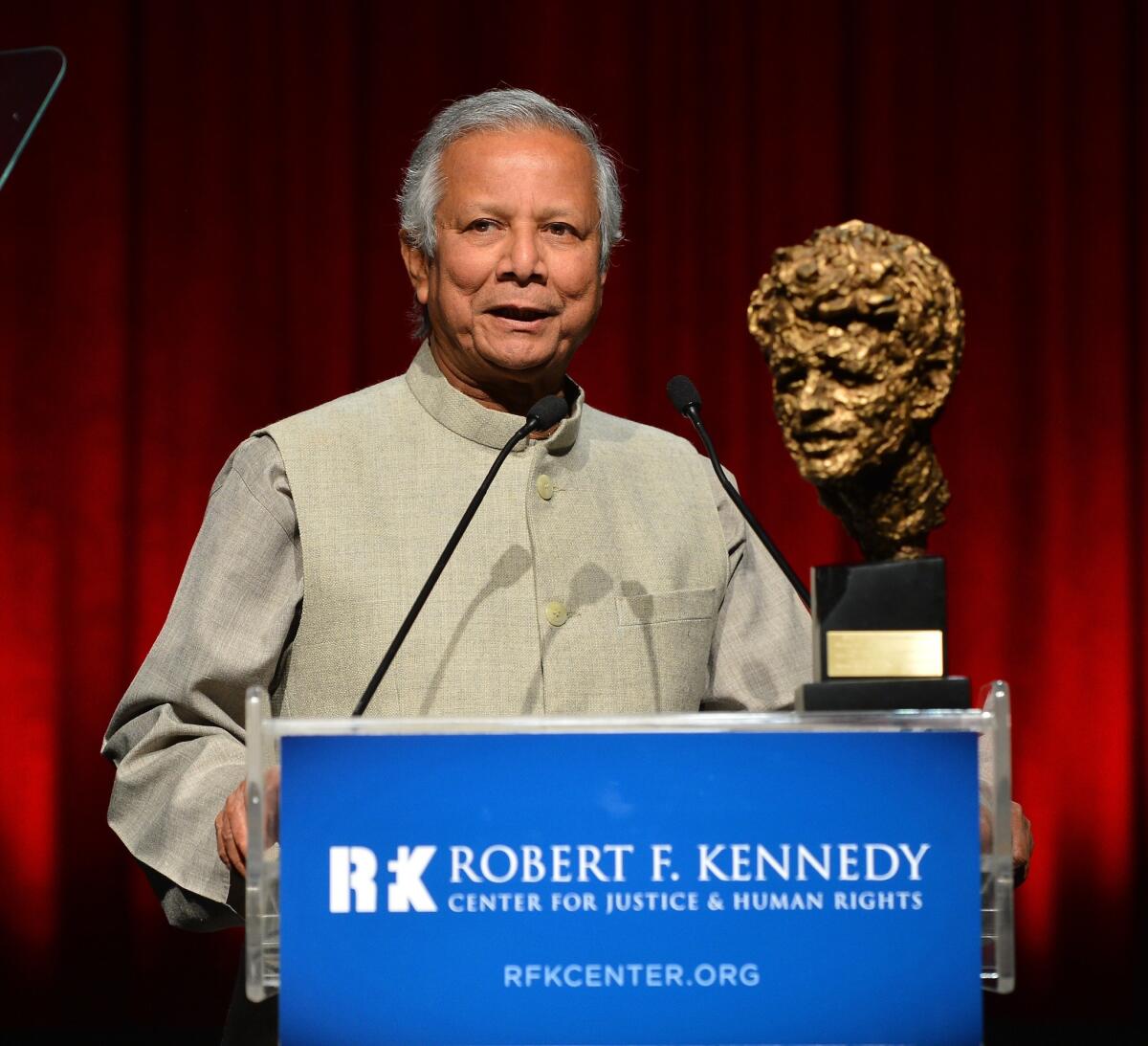

We meet “social entrepreneurs” and “venture philanthropists” such as Muhammad Yunus, the microlending pioneer, and Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay, who both adopt a businesslike approach to social problems; Yunus’ Grameen Bank provides loans to poor Bangladeshis, while the Omidyar Network (ON) invests in products such as d.light, a cheaper, solar-powered alternative to the carcinogenic kerosene lamp.

By seeing the poor as a market rather than a receptacle for aid, Grameen and ON have built profitable enterprises that solve social problems.

These markets are worth a startling amount. Ashoka, the social enterprise network, values the market for healthcare that serves the poor at $202 billion and for food at $3.6 trillion. In the education market, entrepreneurs have been wise to the savings from “disruptive technologies” such as the Internet.

Khan Academy, for example, uses its analytics engine to tailor online learning to students who might otherwise be taught by unmotivated teachers in overcrowded classrooms with outdated textbooks. The profitability of these enterprises makes them sustainable and attractive to donors, but ultimately “they measure their bottom line in social value.”

The authors contend that this social value should be seen as a form of capital, with philanthropists investing in “the trillion dollar market for public good.”

Although the authors have given it a new name, “the solution economy,” the idea is hardly new. The annual Social Capital Markets Conference has been a fixture of the philanthropy scene for years.

Most of the examples in “The Solution Revolution” are well known from David Bornstein’s landmark study of social entrepreneurs, “How to Change the World.”

Meanwhile, Matthew Bishop and Michael Green introduced the idea of the “venture philanthropist” — as engaged, target-driven and professional as any venture capitalist — in their 2008 book, “Philanthrocapitalism: How the Rich Can Save the World.”

Eggers and Macmillan’s work succeeds as a guide to new opportunities to profit from “socially impactful” activities once thought unprofitable. But there is no focus on whether these “solutions” are the best for the problems at hand.

Eggers, an ex-fellow of the neoconservative Manhattan Institute, has written six books outlining his vision for diminished government. That vision grounds “The Solution Revolution” too: “All [government] has to do is get out of the way to let these solution markets work.”

But the authors show little awareness of the market failures that have led to the very problems for which they advocate market solutions. That they cite a problem-ridden, minimally governed country such as Bangladesh so frequently in this book is not so much a success story as a cautionary tale.

Tanjil Rashid is a contributor to the Financial Times of London, in which this review first appeared.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.