Richard Jackson wants to make you feel uncomfortable

- Share via

The sculpture of a giant black Labrador outside the Orange County Museum of Art looks friendly, nose to the sky and tail up. But with a hind leg cocked, “Bad Dog” is designed to spray gallons of yellow paint through a powerful gear pump onto the museum building.

“We’ll see how long it lasts. I don’t think it’s such a big deal, but you never know how people will react,” said Richard Jackson, the 73-year-old artist behind the dog. “Sometimes people feel they should protect their children from such things, then the kids go home and watch ‘South Park.’”

Jackson made “Bad Dog” for his first museum retrospective, opening in Orange County on Sunday. It is also something of a surrogate for the artist himself, if not a true self-portrait.

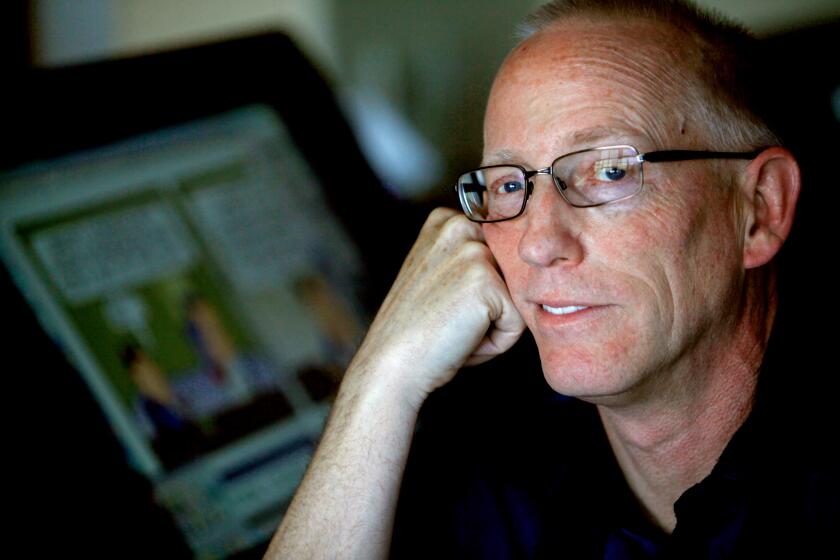

PHOTOS: Artist Richard Jackson

Jackson is a museum outsider, rarely getting shows in U.S. institutions. (A 1988 mid-career survey at the Menil Collection in Houston is the biggest exception.) He doesn’t follow the rules. And he is one messy painter who likes to mark his territory.

For nearly two decades now, Jackson has been building machines for making paintings with a basement inventor’s sort of ingenuity and a wicked sense of humor: sculptures rigged with pumps or other devices designed to spray, spew, splatter, pour, spurt, excrete, fling or otherwise deliver paint onto a surface like walls or floors.

OCMA Director Dennis Szakacs, who curated the retrospective, describes the work as difficult for museums, not to mention collectors who have a wall to fill. “His work is large, it’s messy, it’s complicated, and some pieces require huge amounts of labor only to be destroyed, so it confounds standard museum practice,” he said.

But the challenges are not, Szakacs suggested, gratuitous, and several younger artists are fans. He called Jackson “wildly inventive” and overdue for reappraisal — “one of the most influential and least understood artists working today.”

“I don’t think anybody has expanded the definition and form of painting as much as Richard has.”

The early work

Early on, Jackson pushed painting in new directions by exploiting the sculptural potential of the painted canvas. He also did stunts with canvases akin to the sorts of things that contemporaries Chris Burden and Bruce Nauman were doing to their own bodies.

In the ‘70s, Jackson nailed paintings face down to the floor of his studio. Or he pressed freshly painted canvases onto the wall to stain them with color.

In one breakthrough work, originally installed in 1970 in Eugenia Butler’s L.A. gallery, he propped up a series of eight large canvases to create a maze that the viewer could walk through. He painted the canvases, then forced a clean canvas through the narrow corridor like a spreader, creating Gerhard Richter-like scraped-paint effects throughout the maze.

It all makes for an uncomfortable viewing experience. Once inside the maze, you can’t stand back to view any painting from what feels like a proper distance. And once you enter the inner chamber, you are confronted with the backs of four canvases — further upsetting any expectation of contemplating a painting.

Jackson has just finished re-creating this piece, not seen in California since 1970, for the show. Also in the show will be a new “stacked painting” of the sort first shown in 1980 at the Rosamund Felsen gallery.

In the original version he used 1,000 freshly painted canvases, laying them on top of one another like bricks to make a 16-foot-tall wall. The acrylic paint worked like a sort of glue. At the time, he did everything himself, from cutting the wood for the stretchers to priming and painting the canvases.

This time, for an installation involving 5,050 canvases arranged in a stair-like formation (each stack is one painting taller than the one before), he didn’t make his own stretchers and had an assistant mix paints for him, but he still did the paintings himself, as many as a hundred a day. Most were abstract, but he did a few landscapes to mix things up. “I like trees,” he said.

“I’m interested in what one person can accomplish on his own,” he said from his studio in the foothills of Sierra Madre. “Even if I don’t finish something, to me that’s more interesting than what a corporation could do.”

A prickly individualism

Jackson’s rugged and sometimes prickly individualism has deep roots. Born and raised in Sacramento, he spent his free time hunting on a 2,000-acre ranch in Colusa County homesteaded by his family, who are descendants of President Andrew Jackson. He studied engineering and art at Sacramento State College.

“Both of my grandfathers built their own houses,” he said. “I grew up with tools, not books. I like making things.”

He held down odd jobs like Christmas tree farming and mining for gold in Sierra City before getting his first gallery shows in L.A. in the 1970s. And he worked as a housing contractor for decades, even into the 1990s while he was teaching a sculpture class at UCLA and started showing with the powerhouse gallery Hauser & Wirth. (The late Jason Rhoades, who was once Jackson’s teaching assistant at the university and quickly became “a big pal,” introduced him to Iwan Wirth.)

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Jackson now also shows with David Kordansky in L.A. But “contrary to popular opinion,” Jackson said, “I don’t make any money. There still isn’t a market for my work.”

And now, on the eve of his first museum retrospective, he still sounds rather wary of the art-world success that has largely eluded him.

“Since I’ve become an artist, the whole nature of the thing has changed in a lot of ways. If things were like they are now when I was young, I probably wouldn’t have been interested in art,” he said. “Today it’s more of a business, with artists who are self-promoting and have curators, registrars and secretaries.”

He adds wryly: These days the most important tool in an artist’s studio is his telephone.

Jackson’s studio in Sierra Madre looks more like an auto body shop, complete with power tools, welding and woodworking equipment and milling machine. Outside he keeps two black labs, inspiration for “Bad Dog” and favorite hunting partners. “Duck, pheasant — they’ll retrieve anything.”

Inside one wall is lined with deer antlers. There is no phone or computer in sight.

Another early work in the Orange County show — which at first glance mirrors a corporate mind-set — is “1,000 Clocks,” which made its debut in 1992 at the Museum of Contemporary Art as part of Paul Schimmel’s groundbreaking “Helter Skelter” exhibition of L.A. artists. The large installation consists of a thousand clocks blanketing the walls and ceiling of a gallery, all set to the same time.

But the assembly-line, group-think aesthetic of the work reads differently when you see the primitive gears on the back and realize the clocks are handmade. Jackson built each one himself (“at my own expense,” he adds) over the course of five years out of 44,000 clock parts.

The piece was a strange fit in the MOCA show, which unleashed the dark or grotesque visions of Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy. “My work didn’t really belong in the show,” he said, remembering visitors leaning against his piece for a better view of Kelley’s.

“The piece was about time and turning 50 — I was probably the oldest artist in the show. It needed to be shown on its own somewhere, and needed to have a focus on how it was made: someone spending all this time working on time.”

Not long after that, Jackson started making his machines for painting, which unleashed a torrent or small storm’s worth of paint, typically in unpredictable ways, onto a large surface like the walls of a room.

In one case, it’s an upside-down replica of a Degas bronze ballerina, modified so that paint drips down her legs. In another, it’s a carousel of sculpted deer that shoot paint from their backsides at various targets in the room — a reversal of usual hunting roles.

Art critics have compared this body of work to the jacked-up action painting of Jackson Pollock, taken to an absurd extreme.

The macho swagger — or humor — of it all doesn’t escape Jackson, who calls one of his mechanical works “Painting With Two Balls” after a Jasper Johns work with the same title.

For the most recent version of his work, first made in 1997 and done again this month in Orange County, Jackson sets a 1978 Ford Pinto on its side and positions two large spheres above it. When Jackson starts the car and the wheels start spinning, so do the large spheres — making one large device for flinging paint, when poured from above, across the room.

With these mechanical devices or surrogates, Jackson calls the moment of painting the “activation” of the work. In the case of the Pinto ignition, museum staff gathered to watch the process, but he usually prefers to work privately, no art-world spectacle or ticketed viewings.

“I think it’s better for people if they’re not around. It makes the work more interesting for them, because it forces them to use their imagination,” he said. “If you see how it’s done, it takes the mystery out of it.”

The other reason he doesn’t seek out an audience, he says, is that often something goes wrong. He mentioned a project last year that was designed for the public, part of an arts festival, and failed to work on the first try. Before a crowd of several hundred people, he was getting ready to send a large radio-controlled model plane loaded with paint bombs crashing into a large wall near the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. But before the plane took off, one of rear stabilizers broke.

As Jackson describes it, the crowd soon started to get panicky. But he was energized by the challenge — and worked with men on the ground to glue and tape the stabilizer back on, making for a successful second run.

“When something goes wrong, the people observing start feeling sorry for me, and they think this isn’t going to work,” he said. “But it’s good to have a problem to solve on the spot. It forces me to be creative. So in a way when the trouble starts, that’s when the fun starts for me.”

Given Jackson’s interest in the unpredictable, it’s not surprising that he sounds ambivalent about re-creating older works for the show that no longer exist.

“I don’t want to redo old work,” he said. “But I don’t want to be a crab either.”

Most of all he would prefer to focus on new projects: “I have too many things I want to do and too many things I have to do, and they’re not the same.”

One unrealized project, he said, is to transform a gallery into an inside-out, upside-down log-cabin-style cuckoo clock, in which animal figures jump out of the walls. It would double as some kind of tavern or bar.

Another desire is to crash a full-scale but radio-controlled Cessna carrying buckets of paint. The plane itself is on display at the end of the retrospective, as if waiting for the ideal patron to step in and fund the action-painting.

He would also like to crash a car loaded with paint. In the past he’s talked about using a brand-new Porsche. Now, having spent some time in Orange County, he says a Bentley might do the trick. (“There’s a Bentley on every corner here.”)

What’s the point? “I guess it’s a sort of irreverence: I think I’m always trying to change people and the way they think, so you attack their sensibilities.”

MORE

INTERACTIVE: Christopher Hawthorne’s On the Boulevards

VOTE: What’s the best version of ‘O Holy Night’?

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.