Review: ‘Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV’: Splendid pomp and circumstance at the Getty

- Share via

Louis-Dieudonné — that’s Louis “Gift of God” — became king of France when he was not yet 5.

His widowed mom, the Spanish Hapsburg queen of Austria, ruled in his place as he grew up, along with firm — some would say iron-fisted — guidance from Italian Cardinal Mazarin, Pope Urban VIII’s ambassador to Paris. The road to the little king’s maturity was rocky, what with tangled layers of royal lineage, noble bureaucracies, scheming courtiers, far-flung international intrigues and years of bloody civil war.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

Little Louis-Dieudonné didn’t get much of a classical education during all this. But over the course of nearly 17 years, before he finally assumed the throne as Louis XIV in 1661 — once Mazarin was safely dead and buried — he had a front-row seat in the practical methods of pulling the levers of power. As an imposing exhibition at the Getty Museum shows with splendid pomp and circumstance, big and elaborately woven tapestries were one useful tool.

Yes, tapestries.

Today, we don’t pay a lot of attention to the productions that emanated from Europe’s weaving factories in the great age of Renaissance and Old Master painting and sculpture. That oversight has begun to change in the last dozen years or so, principally through a pair of sprawling extravaganzas at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and two tightly focused Getty exhibitions — “Spectacular Rubens: The Triumph of the Eucharist” last year and now “Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV.”

Charles Le Brun’s “Chateau of Monceaux/December” from “The Royal Residences/Months of the Year.”

But even if we’re only just beginning to play tapestry catch-up, the ruling houses of church and absolute monarchy certainly paid close attention back then. Louis, taking a cue from Apollo when he finally ascended the throne, dubbed himself the Sun King, so that all planets would presumably revolve around his divinely ordained brilliance. “Woven Gold,” with designs after Raphael, Giulio Romano, Peter Paul Rubens, Simon Vouet, Charles Le Brun and others, presents 15 examples of the furnishings of ultimate power.

Tapestries were hugely expensive to produce, especially when threads of wool and silk were wrapped in gold and silver, itself a sign of power. Precious metals produce a vivacious, humbling shimmer across the lush and colorful pictorial expanse, whether illuminated by sunshine or candlelight.

Portable, tapestries were commanding emblems of unequivocal power on the road. A 22- or 25-foot-wide tapestry, unlike a similarly giant painting or a monumental sculpture, could be rolled or folded up, piled atop wagons and transported to a summer palace, hermitage or country house whenever the court took up temporary residence elsewhere.

Like the old American Express ad in which a vaguely familiar celebrity asked, “Do you know me?,” only to be answered by the name printed on his or her prestige credit card, one guiding principle for a royal tapestry was “Don’t leave home without it.” It telegraphed to one and all exactly whom one was dealing with.

At the Getty, where one is dealing with the Sun King, one is also dealing with gross excess. This is the guy who consolidated power in the elaborate halls of the chateau of Versailles, turning his father’s favorite out-of-town hunting lodge into Europe’s biggest, most extravagant palace. Eventually, the sprawling court was brought together there under Louis’ controlling thumb.

By the time he was done — and the exhibition is organized to coincide with the 300th anniversary of Louis XIV’s death — he had 2,650 pieces in his tapestry collection. Some were used as palatial furnishings, many others were stored and brought out for temporary displays.

Needless to say, he did not commission them all. The show, smartly assembled by Getty decorative arts curator Charissa Bremer-David, is divided into three sections. Each is based on how the particular tapestry came into the crown’s possession: acquisition, inheritance or command.

As a collector, Louis bought his way into important histories and dynastic alliances.

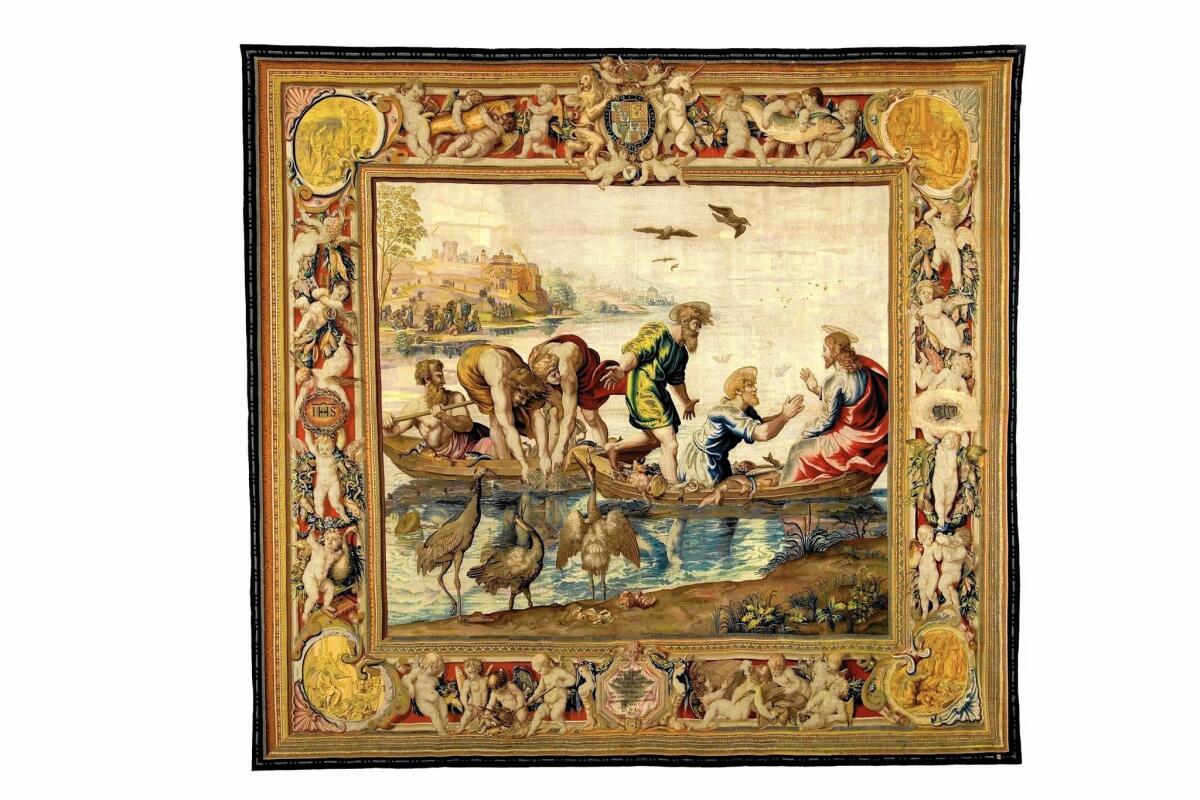

The show’s first tapestry, and perhaps its most beautiful, is from a design by Raphael. Behind a row of strutting, exquisitely observed sea birds on the shore at Galilee, five energetic men in a pair of small fishing boats take an unbelievable haul in their nets. Jesus, seated serenely in the prow, raises his hand in benediction, and Peter kneels in insistent supplication.

Raphael composed this scene of religiously ordained abundance as if it were a carved relief on an ancient Roman frieze — a wall of marble antiquity brought to life in living color. The pagan world is subsumed into the design’s Christian universe, with carefully observed plants and animals from nature’s orderly realm given pride of place.

Even the precise, vaporous reflections in the water record the optical distortions of events unfolding above. This is creation as it is supposed to be, closely observed and wondrous.

There are many reasons Louis would want to own the tapestry along with the rest of the set of Raphael’s “The Acts of the Apostles” from which it comes. One is that it imported into 17th century France the 16th century Italian Renaissance — an artistic high point and a memory of Louis’ Renaissance-era ancestor, Francois I, protector of Leonardo da Vinci.

“The Miraculous Draft of Fishes” also had belonged to Mazarin. It is the second version of a Raphael tapestry in the Vatican, commissioned for the Sistine Chapel. In addition to its artistic brilliance, the tapestry hits a variety of power notes.

Peter Paul Rubens, “Constantius Appoints Constantine as His Successor” from “The Story of Constantine.”

As an heir, Louis’ tapestries helped position himself as rightful occupier of the dynastic throne.

In “The Golden Chariot,” designed in the 1560s by Antoine Caron, a monumental female figure of Immortality rides atop the funeral carriage of King Mausolus, whose beloved wife, Queen Artemisia, would succeed him. The sumptuous spectacle of the gilded cortege, ringed by an ornate border containing cartouches that commemorate the union of Henry IV and Marie de’ Medici, who commissioned the set of Artemisia tapestries, has obvious personal meaning for Louis. Artemisia substitutes for his own mother, who ruled in his place after his own father died.

Finally, as a patron, Louis could tell the stories he wanted told. One of them is a deceptively simple scene of a royal residence during December.

There are two versions of the tapestry, one large and one small (if roughly 10 feet by 11 feet can be called small), both designed by Le Brun as if they were proscenium stages for a theatrical production. The smaller is in the Getty’s celebrated collection of 17th and 18th century French decorative arts and may have provided the impetus for the exhibition. (Most of the tapestries have been lent by Paris’ Mobilier National, repository for much of the former royal collection.)

What’s the action onstage? Out beyond the low wall of the portico, where grand columns frame the scene and a young man and woman are pressed close to a still life of musical instruments and a sumptuous Persian carpet, a landscape unfurls toward the grand Château de Monceau.

A wild-boar hunt is underway, with Louis leading the charge.

Exotic birds from the king’s menagerie strut across the “footlights,” recalling the exquisite row of birds in the same position in Raphael’s “Miraculous Draft of Fishes.” But it’s the bloody hunt so extravagantly framed in the center that compels attention. The Sun King is a fearless warrior, but his role here as heir to Apollo, Olympian deity of poetry and music, merges with that of the Greek god’s twin — Artemis, goddess of the hunt.

Artemis, of course, is the namesake for Queen Artemisia, surrogate for Louis XIV’s mother in the splendid golden chariot tapestry by Caron.

The design by Le Brun is immensely sophisticated, and he dominates the Getty exhibition with seven of its 15 tapestries. Louis established the royal industrial arts factory at Gobelins, soon specializing in tapestry, and he put Le Brun in charge.

Le Brun was not an artist one would describe as striking or flashy but rather an administratively savvy, intellectually astute company man. Without him, who knows whether Gobelins would have flourished.

The Getty’s prior tapestry show, “Spectacular Rubens,” was all about the dazzling pictorial fireworks that the Flemish Baroque master regularly conjured from wool and silk. Rubens’ contribution here — a larger-than-life image of Roman Emperor Constantius passing the reins of power to his son, Constantine — is vividly ordained by a stunning angel swathed in purple and gold. Her swooping aerial form explodes the flat surface plane of an otherwise classical composition, making the transition of power momentous.

There is other fun to be had in the exhibition, starting with an extravaganza of pagan decoration, “The Triumph of Bacchus.” It’s hard to know where to look first, so busily sumptuous are the motifs designed by Giovanni da Udine, a student of Raphael.

The multi-tiered wine fountain sprouting in the center could be seen as a sobering allusion to the purifying blood of Christ — but that only heightens the surrounding rainbow-colored action apparently in need of absolution. The fountain fuels a visually rich orgy of eating, drinking and imminent debauchery.

In perhaps the most startling scene, framed in a tented bedroom at the far left, a priapic centaur makes an advance on a snoozing, no-doubt-drunken Silenus, elderly tutor of young Bacchus, while a voluptuous nymph struggles to intervene. The tapestry, complete with lush borders of ripe fruit and pungent flowers interspersed with assorted personifications of virtue, is like an outtake of “The Aristocrats” — the outlandish 2005 movie that had a hundred comics tell versions of a famous filthy joke whose punchline skewers the plentiful corruption of grandees.

Louis XIV also charged Le Brun with directing the complete makeover of the previously modest château of Versailles, where France’s own aristocratic corruption would one day sink the royal ship of state. You won’t see that happen in “Woven Gold,” of course, but you can easily get the idea of its inevitability.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.