Column: Sydney H. Schanberg was a dogged journalistic role model; journalism will miss him

- Share via

A first job is always memorable. Even more so when your boss is an irascible bearded maniac with a pungent habit of smoking cigars at his desk while railing at the antics of Al D’Amato, the New York senator renowned for his filibusters, ethics issues and penchant for inappropriate utterances.

But working for Sydney H. Schanberg was the best journalism school I could have ever had. The news of his death on Saturday at the age of 82 leaves a hole in my heart — and a bigger one in this pixel-stained trade we call journalism.

In reporting circles, Sydney was legendary: A former correspondent for the New York Times, he had famously covered the 1975 fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and subsequently earned a Pulitzer for his work, “carried out at great risk.”

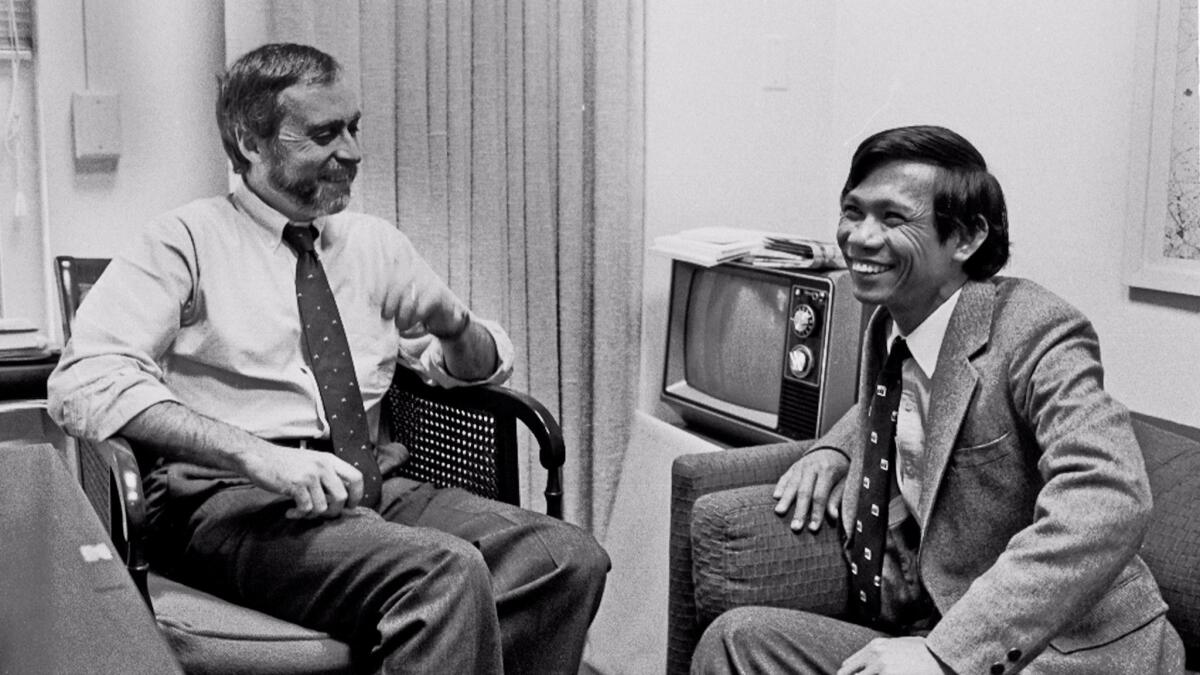

The story of how he and his Cambodian reporting partner and photographer, Dith Pran, remained in Phnom Penh despite being ordered out became the basis of the Oscar-winning 1984 film “The Killing Fields.” (Schanberg managed to get out alive; Dith was sent to what seemed to be certain death in the countryside but ultimately escaped to Thailand after several years of barely surviving.)

By the time I met Sydney, his days of globe-trotting war reportage were behind him. (It was in the early 1990s and he was in his sixties.) He had left the New York Times and was working as a political columnist at New York Newsday, a now-defunct Manhattan tabloid that, for a time, was home to a motley, hard-drinking, hilarious cast of hyper-smart journalists.

I arrived in 1993 — fresh out of college, as Sydney’s research assistant — to a gray-paneled cubicle in the middle of a boisterous newsroom where my job was to dig stuff up in the days before Google. (It was a world of clip files and microfilm and trips to the library.)

From Day One, it was clear that it wasn’t going to be an easy job. Sydney was demanding — of himself, as well as everyone else. He never accepted “I don’t know” for an answer. He’d ask and ask and ask again until he was sure he understood the issues at hand. And he expected no less of me.

More than anyone, he taught me that as a journalist, there are no dumb questions — only dumb answers. He taught me the art of the follow-up question. And he also taught me a thing or two about persistence. “They haven’t called you back? Call again,” he would growl, before disappearing under a heavy cloud of smoke in his office.

For two years, I helped him on all manner of stories — chatting with police informants who would call into the office with colorful code names, filing freedom of information requests to an alphabet soup of government agencies, tracking down the latest of D’Amato’s doings during the whole Whitewater debacle. (Sydney’s clip files on the senator were voluminous.)

The work (and Sydney) could be difficult, but it was a rich learning experience. He cultivated in me a profound appreciation for original reporting — something I continue to hold dear in this era of cut-and-paste journalism.

For all his newsroom gruffness, Sydney was exceedingly ethical and rewarded good work when he saw it. He could also be wonderfully warm, serving a mildly paternal role to the California girl (I was barely 21) who had somehow crash-landed into this very New York newsroom.

There were also the little things: His undying love of the Red Sox, who so often disappointed him (as they did for much of the 20th century). His imitations of public officials at uncomfortable news conferences. And the photo that hung near his desk: A picture of him looking tough on a trip to Cambodia — right as a spectacularly corpulent pig trotted casually through the frame. He was a big deal. But the pig was bigger.

We both left New York Newsday together, in 1995, after the paper was shut down by Times-Mirror (the company which then also owned the Los Angeles Times).

On our last day, as we cleaned out our desks, Sydney announced that he was taking a group of us to the Plaza Hotel for martinis. We stopped in Central Park and he bought a handful of helium balloons, which he let float one by one into an impossibly sunny sky. The rest of us behaved like a pile of raucous schoolchildren, nervous laughter covering up the fact that none of us knew what we’d be doing the next day.

“Don’t worry,” he told me later that evening. “You’ll be fine. One day I’ll work for you.”

I figured then I’d somehow land on my feet. I had to. I’d been trained by the best.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

ALSO

Bill Cunningham dies at 87; iconic New York Times photographer who chronicled fashion high and low

Noel Neill dies at 95; first actress to play Lois Lane

Elie Wiesel dies at 87; Nobel Peace Prize laureate and renowned Holocaust survivor

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.