Critic’s Notebook: Noah Purifoy’s smoldering work of art, ‘Watts Riot,’ is a powerful reminder on the 50th anniversary

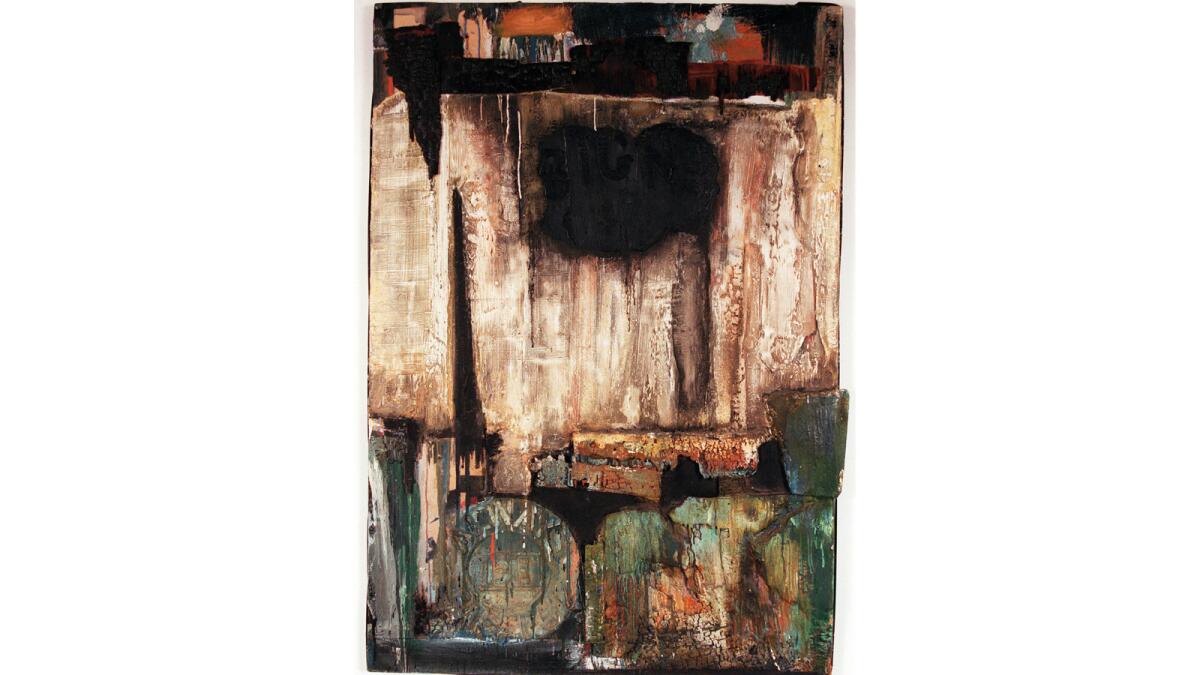

Noah Purifoy‘s “Watts Riot”, on display at California African American Museum.

- Share via

“Watts Riot” is a smoldering work of art, made from materials scavenged from the momentous 1965 uprising in South Los Angeles. Sculptor Noah Purifoy (1917-2004) cobbled together charred fragments of wood, plaster, paint and signage to assemble an exquisite wall relief of murmuring power.

At roughly 3 feet wide and 4 feet high, it’s relatively modest in physical size. For art of the last 50 years, however, “Watts Riot” looms large. As the anniversary of the tumultuous event it observes and memorializes arrives, an initially unassuming work grows in resonant intensity.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

“Watts Riot”: In the Aug. 16 Arts & Books section, an article about Noah Purifoy’s assemblage “Watts Riot” misspelled artist Betye Saar’s first name as Bettye.

------------

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

The six-day Watts rebellion began on the steamy afternoon of Aug. 11, 1965. A crowd had gathered near the corner of Avalon Boulevard and 116th Street to watch as Lee W. Minikus, 31, a white California Highway Patrolman, arrested Marquette Frye, a 21-year-old black motorist, suspected of drunk driving.

Accounts of exactly what happened differ, but only a small spark is needed to ignite a massive conflagration. Long-simmering neighborhood anger over brutal policing, racist real estate covenants and other issues exploded. Five days later, almost 4,000 people had been arrested, more than 1,000 treated for injuries, and 34 Angelenos were dead. Property worth $40 million — $300 million in today’s dollars — lay in ruin.

Culturally the trauma was a turning point. In the riot’s wake, the blossoming perception of Los Angeles as a post-World War II Xanadu for a generation of Americans began to shift. So did a long-established direction in African American art.

After the smoke cleared, Purifoy and his friend Judson Powell gathered up tons of riot salvage — not knowing exactly why, they later said, but compelled to do it. Along with fellow artists Deborah Brewer, Ruth Saturensky and Arthur Secunda, they sifted through the detritus to find the materials to make dozens of assemblage sculptures.

FULL COVERAGE: The Watts riots, 50 years later

Numerous examples are in the retrospective “Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (It remains through Sept. 27.) “Watts Riot,” the greatest of them, is a key work on view in the galleries of the California African American Museum in Exposition Park, where it is a collection touchstone.

Found-object assemblage was the first large-scale Modern movement to emerge in the city in the late 1950s. It had many widely admired adherents when Purifoy picked up the technique.

Take the precocious young African American sculptor Melvin Edwards, still a student at USC in 1963 when he began welding together steel bolts, hooks, spikes, gears, hammers and other found tools to make industrial strength wall-reliefs.

The sculptures fuse oblique visual references to African masks, Cubist constructions, David Smith’s abstract welded-iron sculptures and the chains of shackled slaves. Their wrenching social poetry retains a submerged memory of the material’s original identities and functions. “Lynch Fragments,” Edwards named them.

Assemblage soon became an incisive, wide-ranging method for Bettye Saar, John Outterbridge, Senga Nengudi, Houston Conwill, David Hammons and many other artists. Assemblage built on — and transformed — an established humanist vision depicting both the dignity and plight of African Americans, typified by the powerfully expressive figure drawings of the esteemed Charles White (1918-79).

What emerged in assemblage was a more abstract conception of black consciousness. Today it’s a norm, evident in work by American artists as distinct as Mark Bradford, Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker. “Watts Riot” embodies it.

Purifoy had helped found an arts center at the site of the Watts Towers, arguably America’s greatest modern folk-art masterpiece. Of the towers’ neighbors, the artist once told a reporter, “What if these people could look at junk another way — as a symbol of their being in the world, their being just in relationship to something.”

Their being in the world — battered and discarded, like the broken glass and pottery of the soaring towers but also reassembled and reborn into something beautiful, mysterious and profound.

Purifoy was 49 when he made “Watts Riot,” his decision to be a working artist still relatively new. He graduated from Chouinard Art Institute in 1956 but subsequently taught school, made furniture, was a successful interior designer and more. In the riot’s wake his maturity may have been an asset, given the gravity of the subject.

Works by other L.A. artists are sometimes erroneously connected to the uprising, notably Edward Ruscha’s great “Los Angeles County Museum on Fire” (1965-68). It shows the burning complex floating in a sickly field of chartreuse color.

LACMA opened as a glamorous, art-filled marble palace on Wilshire Boulevard’s Miracle Mile, the city’s most prominent thoroughfare, just four months before and 15 miles away from the riot’s epicenter. It represented a bold bid to mark L.A.’s dynamic postwar cultural emergence. Ruscha depicts it going up in smoke.

Yet the artist has never painted topical subjects. In paintings that precede the LACMA picture — and the riot — by a year or two, he had already set a Standard gasoline station and a Norm’s diner ablaze. Laying waste to pictorial “standards” and “norms” is what an avant-garde artist was supposed to do. Razing an entire art museum made similar sense.

Working in her Venice Boulevard studio, on the other hand, Vija Celmins, then just out of UCLA and now among America’s most admired artists, painted the Aug. 20, 1965, cover of Time magazine sporting the banner “The Los Angeles Riot.” Three horizontal images show an aerial view of neighborhood stores in flames, the charred corpse of an overturned car and five looters running down the street as seven onlookers watch. Celmins’ entire painting is in shades of gray.

A Latvian émigré who fled Nazi-occupied Riga with her family as a child, Celmins had already painted “T.V.,” a fantasy showing an exploding World War II airplane on a television screen. Mass-media framing lends emotional distance to a tragic personal drama.

Watts was among the first such civil disturbances to receive extended mass-media exposure on a grand scale. The early 1960s ushered in a profound transformation in news delivery as TV grew to dominate the media landscape. Corporate television nearly shut out African Americans from regular programming, so the riot had an especially antagonizing impact.

In Celmins’ delicately hand-painted magazine cover, the uniquely personal chafes against the corporate and impassive. Art is a quiet path for slow contemplation, mass media a dramatic avenue for swift disposal. The next week always catapults a new cover — this time buoyant, about NASA flight director Chris Kraft.

Fifty years on, Purifoy’s art smolders.

The rough, plastered wood surface of “Watts Riot” is mostly smoky black and smudged and yellowing white. Flashes of rainbow iridescence dart across the surface from seared paint mixtures. Bits of blue, crimson, orange and green flicker within the ruins.

A vertical rectangle seems to hover in the center, as if a window is opening onto terrible darkness. Above, the word “sign” is picked out in low-relief lettering. A circular disk below at the left pleads, “Always be careful.”

The assemblage is an enigmatic talisman. James Baldwin’s blistering masterpiece “The Fire Next Time” helps unravel it. The book topped the 1963 bestseller lists with a pair of essays interrogating what he called, in the day’s vernacular, “the Negro problem.”

Baldwin asked, “Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?” America was that house, burning with cruelty in its self-destructive Jim Crow racism, both blatant and unacknowledged.

Los Angeles was hardly exempt. The city’s economic system was rigged in favor of the local white majority — a fix reaffirmed in the riot’s buildup.

Real estate is integral to equal opportunity for economic health. But as postwar L.A. boomed, the federal government supported discriminatory practices.

Journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates explained in a widely admired story for the Atlantic last year how the 1933 federal Home Owners’ Loan Corp., not a private trade association, “pioneered the practice of redlining, selectively granting loans and insisting that any property it insured be covered by a restrictive covenant — a clause in the deed forbidding the sale of the property to anyone other than whites.”

A debate exists about whether HOLC real estate maps caused or simply reflected redlining, but segregated white neighborhoods were inarguably flooded with millions of tax dollars. The agency’s 1939 L.A. map paints the Watts neighborhood bright red.

In 1964, insult was added to injury. Proposition 14 was a ballot initiative to repeal the new California Fair Housing Act, a hard-won legislative effort to end racial discrimination in public and private housing. The conservative view held that property rights trump civil rights.

“If an individual wants to discriminate against Negroes or others in selling or renting his house,” declared budding L.A. political star Ronald Reagan, “he has the right to do so.”

The ballot measure passed by a 2-to-1 margin, grabbing 70% of the L.A. County vote. Later ruled unconstitutional by the California Supreme Court, the proposition and its passage nonetheless landed as a civic gut-punch.

Baldwin turned to “Mary Don’t You Weep” for his book’s title. A popular spiritual since slavery, its coded lyrics merged solace with inspiration. Black Americans sang of the Genesis flood-myth, which drowned worldly wickedness to clean the slate.

As the floodwater receded, a warning came. “God gave Noah the rainbow sign, no more water — the fire next time.”

Noah Purifoy’s rainbow sign came in the fires of August 1965. Transforming an actual chunk of local real estate, it blossomed in the iridescent, melancholy beauty of “Watts Riot.”

Twitter: @KnightLAT

MORE:

Full coverage of the Watts riots, 50 years later, from the Los Angeles Times

50 Years after Watts: ‘There is still a crisis in the black community’

Stunned by the Watts riots, the L.A. Times struggled to make sense of the violence

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.