Artist Alberto Lescay didn’t just create Cuba’s largest sculpture, he’s teaching a new generation

- Share via

Cruising along Avenida Raul Pujol, weathered brown hands on the wheel of his late-model Hyundai economy car, Cuban artist Alberto Lescay smiles and points toward El Parque Zoologico, which sits about a mile down the road from his private workshop in the stately Vista Alegre neighborhood.

More than just welcome open space amid the residential buildings in this urban development about four miles east of central Santiago, the park outside the city’s zoo holds a trifecta of elements that have been crucial in the life and career of the renowned painter and sculptor.

“That tree is ‘El Arbol de Paz’ [The Tree of Peace],” Lescay, 66, says, referring to the site where Spanish military forces in 1898 surrendered during the Spanish-American War in which Cuba gained its independence from Spain.

“The sculptures in the park were very inspiring to me seeing them when I was young,” he adds, explaining the second reason the park is so significant for him. “They inspired me to become a sculptor.”

El Arbol de Paz holds one other intensely personal memory for him. “That is where I had my first kiss,” he said, a broad smile spreading across the face framed by an unkempt salt-and-pepper mustache, beard and tightly curled hair.

He’s speaking in Spanish, which is translated by one of his two car passengers who are part of a group of about two dozen U.S. visitors exploring the music and arts of Cuba. Lescay is taking the afternoon to act as host and unofficial ltour guide.

Beyond bringing visitors to this spot where Cuban history, culture and romance are inextricably entwined for Lescay, the artist is also boosting his profile in the U.S.

His works are on display through Jan. 6, along with pieces created by his artist-son, Alejandro Lescay, in “Vuelo Directo/Non-Stop” (Direct Flight/ Non-Stop) at the Cuban Art Space/Center for Cuban Studies in New York City. He also contributed samples of his abstract primitive sculptures and multimedia paintings at the recently concluded 2016 Art Basel exhibition in Miami.

At home, he is most widely known for designing and helping build the mammoth monument in Santiago memorializing Antonio Maceo Grajales, the Cuban general for whom the international airport in Cuba’s second-largest city also is named.

Dominating the center of Santiago’s Revolution Square, the work, called “El Titan de Bronce” (The Bronze Titan) — after Maceo’s nickname and the metal chosen for the 53-foot-high sculpture — is the largest statue in the country. Maceo is seen on his horse, portrayed rearing up as its master waves his hand toward an implied battalion behind him. A few yards away, thrusting up from the hilly soil of Revolution Square, are 23 massive angular steel blades crafted from some 650 tons of Russian steel. For many, the blades represent the machetes that were a key weapon of 19th century Cuban troops.

Lescay said the idea was twofold: to invoke the general leading his troops as Cuba fought for independence from Spain more than a century ago and to create a gesture of welcome to those entering Santiago by way of the major thoroughfare leading into the city that passes next to the sculpture.

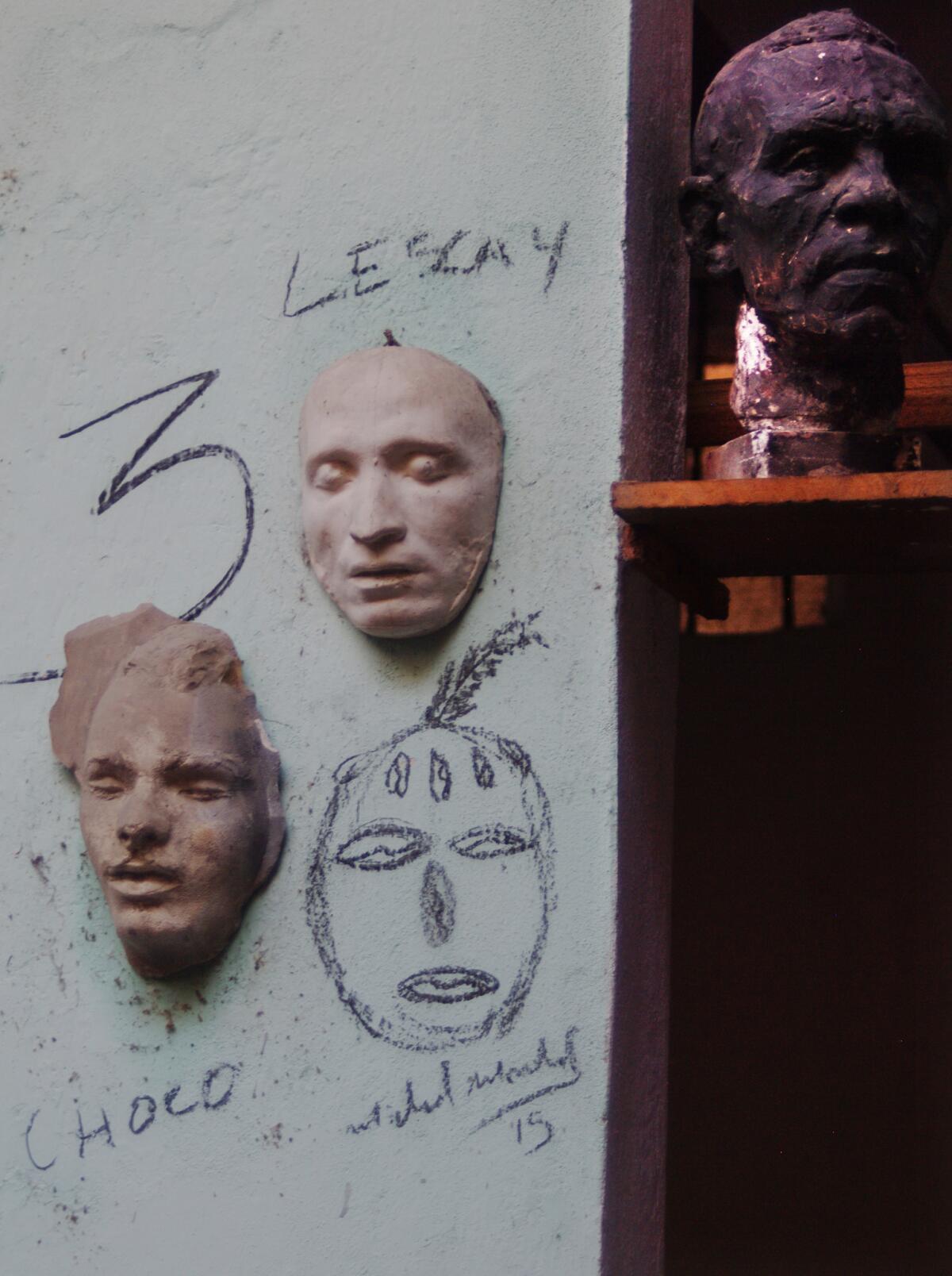

“I imagine you know a little about Antonio Maceo and how he was a source of inspiration for the world, not just for Cubans,” Lescay said a day earlier while leading a casual tour of his primary workspace in Santiago, where he not only creates his own pieces but trains and mentors younger Cuban artists.

“The quality of this man as a military man was greatly admired, even in Europe,” he said. Lescay’s rich baritone voice exudes a gentleness of spirit whether he’s speaking in stentorian tones of his respect for Cuban culture or smiling as he periodically peppers his comments with a witty quip.

I always had Maceo as a role model. My grandfather fought in the war of independence ... so I really wanted to win the contest.

— Alberto Lescay, on winning "The Bronze Titan" commission

When the monument was dedicated on Oct. 14, 1991, Fidel Castro attended and Cuba’s longtime leader passed by it one final time earlier this month as his country-spanning funeral procession stopped in front of Lescay’s work upon reaching Santiago for the internment of his ashes.

“I like the combination of the traditional and the very modern in his work,” says Sandra Levinson, executive director of the Center for Cuban Studies, who met Lescay about 25 years ago, near the beginning of what is known in Cuba as the “special period” following the collapse of the Soviet Union and with it, the financial and other infrastructure support Cuba had long received from the U.S.S.R.

“In the Maceo sculpture, you’ve got the traditional hero on the horse, but you also have these very conceptual machetes flying up out of the ground,” Levinson says.

“Also, I think as a person, [Lescay is] so centered, yet he’s not in the least bit obsessive. He’s very concentrated about his art and his commitment to [Cuban] society, and the way he can help younger artists,” she says, adding that the New York exhibition includes a few of his small-scale bronze sculptures, paintings, drawings and sketches.

“The way he moves through life, quietly, firmly, very strong — that’s very impressive,” she says. “He’s not an average Cuban — he’s very low-key…. One of the reasons we chose to invite him [to exhibit here] was that each time I took a group to Cuba on an art tour, the visit with Alberto was the highlight of the trip.”

Bernardo Navarro Tomas, the center’s project manager and a Cuban artist himself who has lived in the U.S. for 13 years, adds, “His work is amazing. It has a strong influence of the abstract expressionists, but it’s not completely abstract.

“He also uses representational images of the vodou religion that is a strong influence in that part of Cuba, that eastern part of the island that’s so close to Haiti,” Tomas says. “There’s a difference between that and the iconography of the Yoruba religion you see on the western part of the island.”

For Lescay, like many of the 11 million Cubans living on the island, Castro remains a folk hero.

“As a man, he was extremely simple, and had a common appearance,” Lescay told an interviewer shortly after the Nov. 25 death of the man frequently referred to as “El Comandante,” or more often among Cubans simply “Fidel.” “But within seconds of talking to him, you realized that, no, although the way he communicated was ordinary, his thinking was monumental, extraordinary. I feel very sorry. But men like him do not die — death is not for those men. The legacy of Fidel will be eternal — he will be missed by the whole world, not just Cubans, but all humanity.”

Although Cuba is rife with statues memorializing military heroes such as Maceo and Capt.-Gen. Carlos Manuel de Cespedes, as well as cultural figures like 19th century revolutionary poet Jose Marti, there are no statues in the country of Castro.

That is by decree — a policy that helped Castro maintain a well-cultivated public persona as a man of the people. Not better or worse than any other child of La Revolucion, the 1959 coup in which Castro and his comrades overthrew U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencia Batista.

Lescay won the commission to build the Maceo monument more than a quarter-century ago.

“For me personally, I always had Maceo as a role model,” he said. “My grandfather fought in the war of independence, so I always associated by grandfather with Antonio Maceo. So I really wanted to win the contest.”

The commission came with a substantial cash award. Lescay, however, declined the prize money, asking instead that the government fund a foundation he had dreamed of creating to pass along skills he developed through studies at universities in Santiago and Havana as well as during six years he spent further developing his art in Leningrad, Russia (now St. Petersburg).

It was in Russia that he embraced that country’s penchant for massive outdoor sculptures and monuments, putting his own spin on that literalist tradition with elements of abstract expressionism.

At the time the Maceo monument project began, there was only one artist he knew who was versed in the techniques of shaping such vast quantities of bronze — and, Lescay says, “he was over 80 at the time.”

That’s when he realized, “In order to make this [Maceo monument], we had to create a school.” Many of the earlier generation of artists who taught him were dying off, and fewer young Cubans were being groomed to take their places.

A team of nearly 100 other artists was assembled, and they spent nine years on the piece that was dedicated in 1992. “We had to melt over 100 tons of bronze to make it,” Lescay says.

The organization that grew out of that project, Fundacion Caguayo para Las Artes Monumentales y Aplicadas (Caguayo Foundation for Monumental and Applied Arts), is 21 years old. It operates through Cuba’s Cultural Ministry and also is a member of the Madrid,-based Latin American Confederation of Foundations.

Lescay is passionately and enthusiastically involved in many areas of the cultural life of Cuba and more broadly of the surrounding Caribbean.

Other large-scale sculptures he’s made dot the countryside, including another massive work, “Monumento de Cimarron” (Monument to Runaway Slaves), perched on a hilltop overlooking Poblano de Cobre, site of a 1731 slave revolt. In his studio, he also has a striking bust of Haitian revolution leader Francois-Dominique Toussaint L’ouverture.

His bold abstract paintings hang in numerous galleries, and he was given a rock star’s greeting one evening when he dropped into the Casa de Trova — a hall for live music and dancing — just off Plaza Cespedes at the heart of Santiago. He demurely acknowledged the ovation.

As an esteemed national figure, Lescay has the option of living a comfortable life in the nation’s capital. But he prefers Santiago, where he was born, and where he has helped establish and continued to support the Galeria Rene Valdes, a space for artists to exhibit works and interact as part of the city’s vibrant cultural community.

He watched unobtrusively from his seat at the edge of the gallery’s patio during an early evening small-scale performance by nueva trova singer Raul Torres, a young musician following in the footsteps of pioneering Cuban singer-songwriters of the ’60s and ’70s Silvio Rodriguez and Pablo Milanes, and their immediate successors such as Carlos Varela and Frank Delgado.

Lescay also has set up a communal live-work space several miles away from the gallery and his workshop in the Vista Alegra neighborhood, a compound called Los Mamoncillos (The Booties) near the beach at the outskirts of the Reserva de biosfera Bacanao.

On the drive that began with him pointing out the Tree of Peace, he stops en route to the arts compound for a detour through a massive outdoor sculpture garden in Baconao Park.

Lescay proudly points to gargantuan abstract pieces created by artists from Spain, Germany and other countries who received commissions for works also executed on a grand scale.

It’s another example of the regard with which arts are supported by Cuba’s “tropical socialist” government. All Cuban citizens receive subsistence levels of food, income, free housing, medical and dental care but still contend with “la lucha,” the daily struggle to make ends meet, much less to be able to work toward better living or working conditions for themselves and their families.

White-collar professionals often hold second or third jobs driving taxis or tending bar to supplement their governmental income.

That puts Lescay among the privileged few, with relatively comfortable living spaces both at his workshop studio and at Los Mamoncillos about 20 miles away.

In various ways he’s continuing with his own version of la lucha: The desire not just to share the knowledge and skills he has learned from others through most of his life to a new generation of Cuban artists, but also instill in them a similar commitment to pass that torch along to yet younger generations.

“Es mi sueno,” he said quietly. “That is my dream.”

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

For Classic Rock coverage, join us on Facebook

ALSO

The 'nueva trova' music of Cuba's Carlos Varela feels as timely as ever

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.