Are you smarter than TV execs?

- Share via

Ready, contestants? Here’s your bonus question: Have TV quiz-show questions become dumber, and have the shows’ rules grown wimpier, as producers pander to ever-lower audience expectations and the viewing public’s general intellectual flabbiness?

Good luck, panel!

(Sound of time-filling musical interlude.)

OK, time’s up. For those of you playing along at home, the correct answer is ...

Boy, have they.

Consider the premiere episode of the new Fox hit, “Are You Smarter Than a 5th Grader?,” in which a contestant grappled with the daunting complexities of arithmetic. “Two times five equals ... ?” he asked himself aloud, genuinely struggling.

It wasn’t a trick question. The answer is still as plain as the fingers on two hands.

“Are You Smarter” suggests how far down the de-evolutionary scale quiz shows have tumbled. Throughout TV history, quiz shows measured how smart their contestants were, rewarding them for their gray matter and their lightning reflexes. “Are You Smarter” celebrates the opposite, trafficking in the dimness of its adult contestants and glorying in their embarrassment.

The show’s underlying premise is that its questions are within the intellectual grasp of a 10-year-old but out of reach of most adults (although it’s not clear how smart the 10-year-olds really are since, as a disclaimer notes, the producers supply the kids with workbooks to help them bone up on material covered during the show).

Some of the program’s questions are difficult, but it’s unusual to get more than two real tough ones in a row. Among the questions in the debut episode: Name the ship the Pilgrims sailed on from Plymouth, England, to the Plymouth colony in America in 1620. Name the closest star to the Earth. What country has the longest shared border with the United States?

TV executives call those kinds of questions “relate-able,” by which they mean “unlikely to challenge viewers too much and thus make them feel bad about themselves.”

More than a few viewers apparently appreciate the approach. “Are You Smarter’s” elevation of familiar, simple facts to brain-twisting stumpers has proved to be monstrously popular, attracting a larger audience than any new show in the Fox network’s history, about 26.5 million (although it admittedly was helped by following the even more popular “American Idol”). The quiz show’s second episode drew 23.4 million.

It’s not just about the difficulty of the questions, though, or the lack of it. As with “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire,” the rules of “Are You Smarter” stack the deck in the contestant’s -- and by extension, the viewer’s -- favor. On “Are You Smarter,” participants have virtually unlimited time to answer, and can even officially “cheat” by peeking at the answers their child partners have supplied. If the adult contestant answers incorrectly, he can still be “saved” -- that is, awarded a correct answer -- if his partner has gotten the question right.

“Millionaire” seemingly invented that sort of crutch when it ushered in the prime-time quiz-show Dark Age in 1999. It offered contestants “lifelines” whenever its multiple-choice questions got too rugged.

Now, the prime-time NBC quiz show “1 vs. 100” makes it even easier: Instead of “Millionaire’s” four multiple-choice answers, it reduces the possibilities to just three, one of which is often absurd on its face (sample question from last week: “If Vanna White was shopping at a ‘white sale,’ what would she likely be buying? (a) linens (b) a used car (c) a vowel”). Some of the new shows have also adopted “Millionaire’s” rule that enables contestants to walk away with their accumulated cash after they’ve reached a certain plateau -- and after they’ve heard the next question.

It wasn’t always like this, kids.

Many of the quiz shows that riveted the nation in the 1950s were positively Einsteinian compared with today’s. It was a different era, of course. TV was a new medium, and trying very hard to prove it was respectable, even educational. So shows such as “The $64,000 Question,” “Dotto” and “Twenty-One” rewarded those with encyclopedic knowledge in such categories as opera, science and Shakespeare.

“By the standards of ... a later epoch, the intellectual content of the 1950s quiz shows was downright erudite,” wrote John Doherty in a history of quiz shows for the Museum of Broadcast Communications, located in Chicago. “Almost all the questions [on these shows] involved some demonstration of cerebral aptitude -- retrieving lines of poetry, identifying dates from history, and reeling off scientific classifications, the stuff of memorization and canonical culture.”

True, some of the shows were as crooked as a surgical scar, but they were still plenty smart. In their infamously fixed showdown on “Twenty-One” in the mid-1950s (dramatized four decades later in the movie “Quiz Show”), contestants Charles Van Doren and Herbert Stempel battled over biblical references, the volumes of Churchill’s wartime memoirs and the names and fates of the wives of Henry VIII.

It’s doubtful that anyone would have bought “Twenty-One’s” scam if Van Doren had been locked in the isolation booth to sweat out the sum of five times two.

Although that heyday ended abruptly with the exposure of fixed results, more challenging games survived on the margins. “GE College Bowl” -- the name says it all -- ran from 1958 to 1970. And “Jeopardy!” helped revive the format with its debut in 1964. Like “College Bowl,” “Jeopardy!” contestants had to have a wide range of knowledge, and had a limited time to supply each answer. The game also required some skill at wagering.

“Jeopardy!” survives to this day, of course, but it hasn’t been immune to the general pressure to dumb down, says Steve Beverly, a professor of broadcasting at Union University in Tennessee who maintains the Web site TVgameshows.net. Nowadays, he says, the categories are narrower -- fewer foreign phrases, more pop culture categories -- and the questions are often written to point toward an answer.

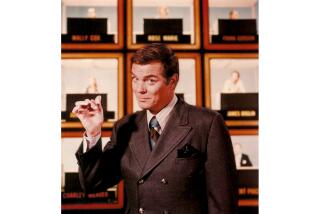

In “Jeopardy!’s” first incarnation, for example -- with host Art Fleming in the 1960s and early ‘70s -- a “Final Jeopardy!” question might contain a minimal phrase, forcing contestants to supply a fairly complex question, Beverly says. That is, in a category such as U.S. presidents, the clue might be “Our American Cousin” -- to which a correct response was some version of, “What was the name of the play Lincoln was watching when he was assassinated?”

In “Jeopardy!’s” current version, the process is inverted, so that the clue carries more hints. Today, Beverly says, host Alex Trebek might read the Lincoln question this way: “He was watching ‘Our American Cousin’ on the night of a fateful event.” A correct question would be, “Who was Abraham Lincoln?”

Why has that happened? Beverly thinks the intellectual deterioration of quiz shows mirrors a decline in intellectual standards among viewers. “We have less of an expectation of ourselves that we’ll learn rigorous material today,” he says. “We have accepted a degree of mediocrity in education. We don’t really want to work too hard to achieve success.”

So quiz shows are dumber these days because they have to be to attract an audience.

Fred Wostbrock, co-author of “The Encyclopedia of TV Game Shows” and the agent for such game show legends as Bob Eubanks, Monty Hall and Chuck Woolery, blames young viewers, in particular. Because advertisers want to attract younger people, he argues, it’s not surprising that the content of quiz shows has become more frivolous to lure them.

The effect, he says, is that we might never again see the likes of such classic game shows as “Password,” in which a contestant tries to get a partner to say a secret word by offering one-word clues. “You could get ‘kangaroo’ by saying ‘pouched,’ ‘marsupial’ and ‘Australia,’ ” Wostbrock says. “With MTV and ‘Entertainment Tonight,’ do young people still read? I doubt very many would know what a ‘pouched marsupial’ is anymore.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.