From the Archives: Haskell Wexler aims his camera at Occupy L.A.

- Share via

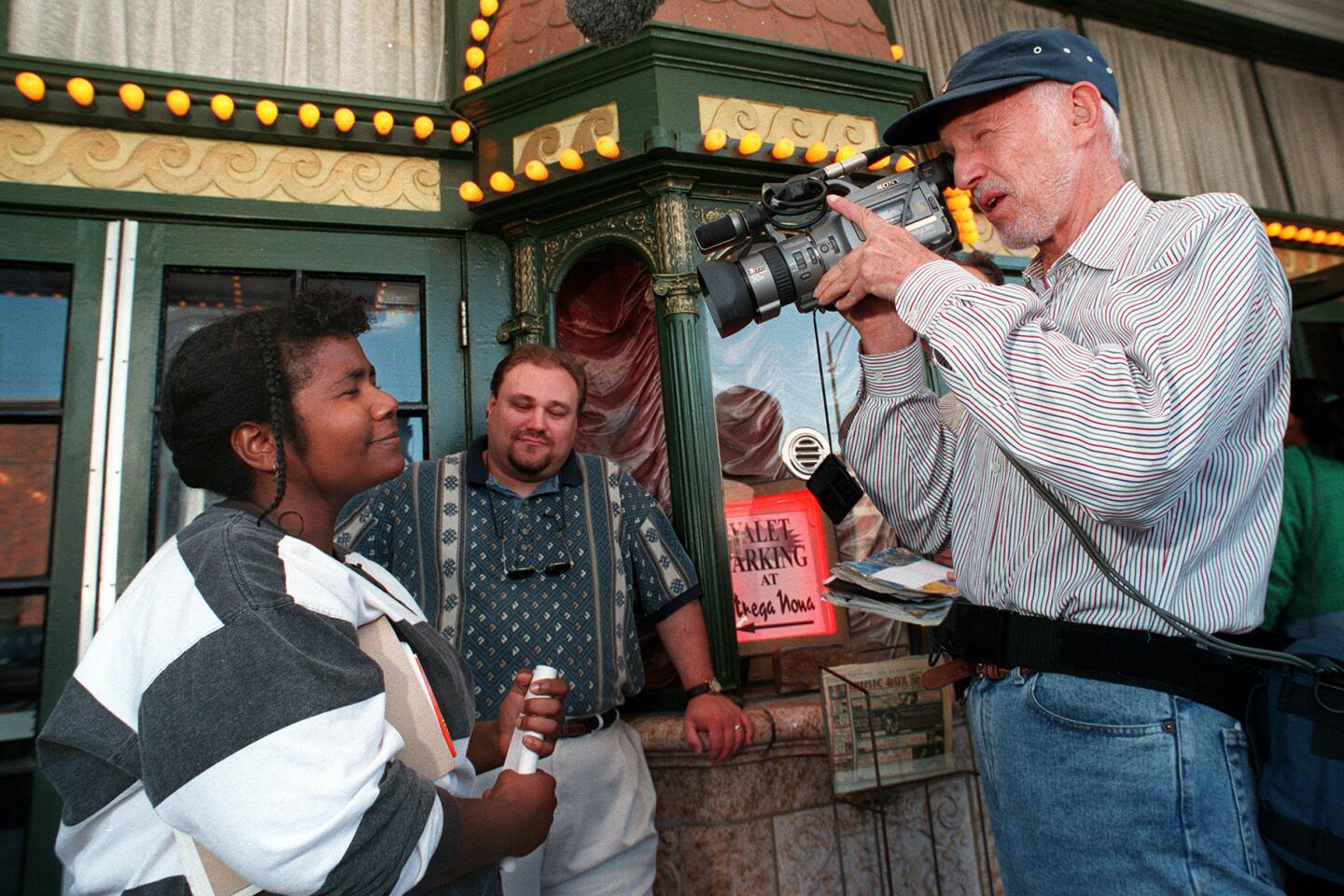

The encampment around City Hall known as Occupy L.A. has drawn the interest of photographers and journalists from around the world, but few arrive with quite the same resume as that of Haskell Wexler. The two-time Oscar-winning cinematographer has made several visits to the protest site, using a small hand-held digital video camera to document what he finds there.

Now 89, Wexler has begun posting short documentary vignettes online about the people camped out in downtown Los Angeles. A lifelong liberal and union activist, Wexler was an early visitor to the protest, which began Oct. 1.

“Things were going on around the country — certainly in New York and even here — for a number of weeks before the conventional media paid any attention,” Wexler said. “I wanted to go down there and find out what was happening.”

He was drawn to both the cause of economic justice and the political theater, feeling some kinship with the protesters despite what he acknowledged was the comfortable lifestyle of a successful Hollywood cinematographer.

“You can take that insulation and figure you’re an old guy and you [already] did your thing,” Wexler said, “and then something inside me gets reminded that my ‘thing’ is what makes me alive — to be able to have a camera and an idea and an urge that gives me pleasure.”

Documentary filmmakers Alan Barker and Joan Churchill have accompanied Wexler on a couple of his trips to Occupy L.A., as part of their three-year project about the cinematographer, and have watched his particular interviewing style. Barker says that Wexler’s “activism has been continuous his whole life” but that he often challenges protesters to explain their positions.

Added Churchill, “There was one moment where he approached a group of four middle-aged people, and he said, ‘You don’t look like red pinko communists!’ And the guy said, ‘Who are you?’ ‘I’m Haskell Wexler.’ ‘Oh, why didn’t you tell me? I’m such an admirer of your work!’”

You can take that insulation and figure you’re an old guy and you [already] did your thing, and then something inside me gets reminded that my ‘thing’ is what makes me alive.

— Haskell Wexler

Wexler’s career began in documentaries and television, but he soon moved into major motion pictures with Elia Kazan’s “America, America” in 1963. Just a few years later, he won his first Academy Award for the 1966 film “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’”; he got his second for the 1976 film “Bound for Glory.” His work has also been seen in such iconic films as “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and “In the Heat of the Night.”

He is just as acclaimed for writing, directing and shooting the low-budget “Medium Cool,” a cinéma vérité feature shot amid the real protests and violent police action outside the Chicago Democratic Convention in 1968. At one point in that film, as the camera inches closer to a tear-gas cloud and a wall of police officers, a voice off-camera famously can be heard warning, “Look out, Haskell — it’s real!”

It’s been just as real in downtown Los Angeles, though far less dangerous to this point.

“The difference between the demonstrators in 1968 and the ones I saw today was part of my education,” Wexler said. “This movement is a threat to the system at its core. There was nothing in ’68 that even dealt with an economic system which is incompatible with a democracy. One thing I did see in common was the idea of theater — the ideas of show.”

Wexler sat at the kitchen table of his office high up in a Santa Monica apartment building, where an assistant worked at a computer with images from Occupy L.A. Behind him is a bookcase filled with volumes on movie history and politics. Across the room, his Oscars and other awards sit on a tall cabinet. He pulled out the small HD camera he’s been using. “You want something that doesn’t look professional, and you want something that is unthreatening,” he said.

During a recent trip to a Chicago film festival, he stopped by the Occupy Chicago protests in his hometown. “In Chicago, they had more overt union participation,” he recalled. “Chicago seemed more working class than here, though the age was pretty spread.”

In 2007, Wexler was cinematographer on an episode of HBO’s “Big Love,” but most of his work now is in documentaries. “The main difference in documentaries is that it’s closer to the skin,” he says, comparing it to the huge productions of a feature film. “You’re more in control, it’s more yours and maybe two other people that are working with you. Documentaries, I really like.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.