The California Cook: Cookbooks that bring comfort

- Share via

At first glance, the story in the local paper seemed to have been written for me: “Decorating With Books.” My house is swamped with cookbooks, they’re stacked on just about every horizontal surface and, yes, some are even arranged on shelves. So I thought it might be a kind of a “When life gives you lemons” thing — maybe this was going to become a trendy new style in home décor?

Sadly, the story turned out to be about businesses that sell impressive-looking books — by the linear foot — to interior decorators to fill their clients’ bookshelves. OK, so my stacks of old cookbooks are still not quite ready for Architectural Digest. But that doesn’t mean I’m going to change anything. I wouldn’t give them up for the world.

Generally speaking, my books can be divided into three groups. The ones I use every day for research; the ones I use for deep research, which I look at only once in a while; and the ones that I almost never use at all.

It may seem odd, but this latter group is the one I treasure most. They’re the heart of my collection, and, as any true collector will tell you, we buy for love, not utility. Besides, I also have beat-up, working copies of most of them for when I actually want to cook something out of them without getting my favorites all sauce-stained.

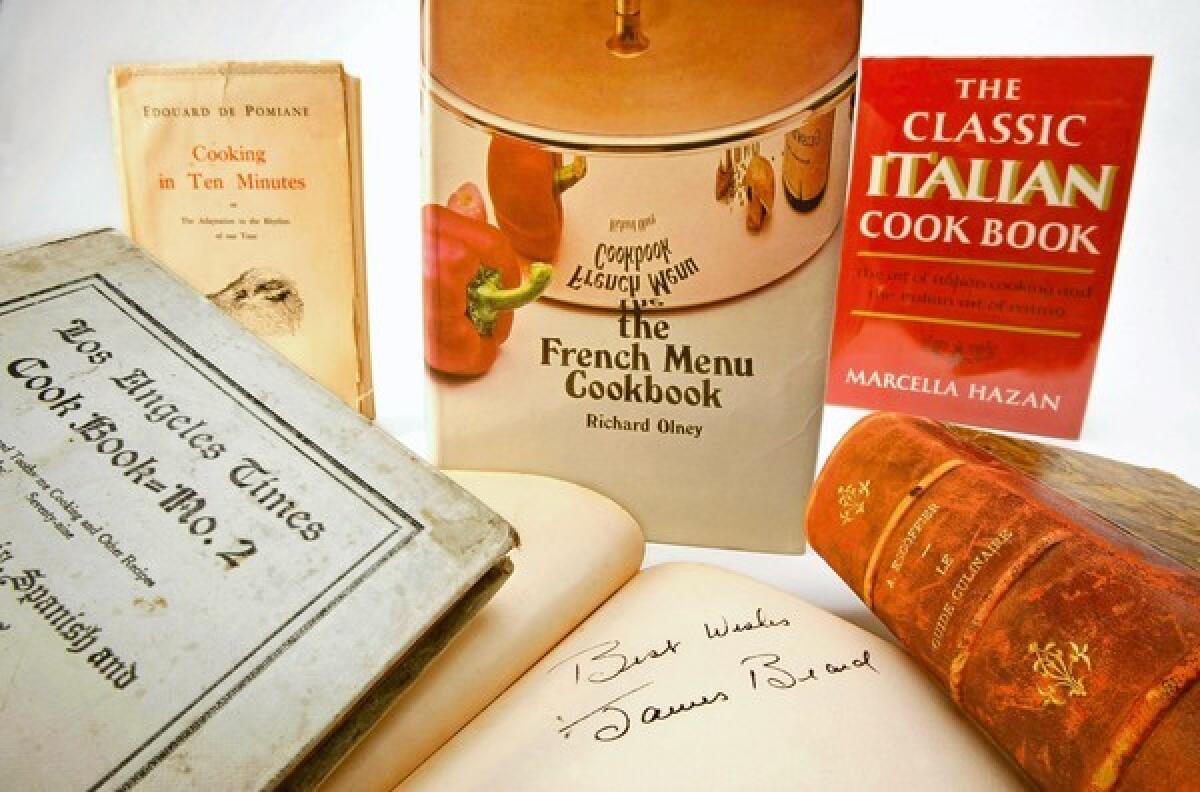

Every one of those books not only tells a story but also has one of its own. There are some oldies in there, like the 1905 “Los Angeles Times Cook Book No. 2” (featuring “Old-Time California, Spanish and Mexican Dishes/Recipes of Famous Pioneer Spanish Settlers”). I’ve been searching for “No. 1” for years with no luck.

I’ve also got a beautiful red leather-bound first edition of Escoffier’s “Le Guide Culinaire,” published in French in 1903, that was the gift of a very generous friend whose grandfather was a chef (his recipe for plum pudding is handwritten inside).

And there’s an 1894 “White House Cookbook” too, inscribed: “To our dear Elmer, for faithful service, Nellie.” That reads like the introduction to a “Masterpiece Theatre” miniseries.

I’ve got a lovely copy of “Cooking in Ten Minutes” from one of my all-time favorite authors, Edouard de Pomiane. This is the book in which he wrote that the first thing to do when you step in the kitchen is start a pot of water boiling: “What’s it for? I don’t know, but it’s bound to be good for something.” The book’s undated but appears to be from just after World War II, published by the Pazifische Presse in Los Angeles, which was a short-lived house established here by and for German expatriates during and just after the war.

But the real pride of place in my collection — the heart of hearts, if you will — belongs to a set of signed first editions of the first books by the authors who have meant the most to me.

First books are special things. By definition, they’re written before the author has established a reputation — or even become an “author.” They’re like soap bubbles released out onto the breeze, full of hope and work, and all but a few suffer ignoble ends. These are the books that have not only survived but have thrived.

Holding a signed first of a first gives me a tangible connection to one of my heroes at a time when they were just starting out.

This collection started almost accidentally. I spotted a copy of James Beard’s “Hors d’Oeuvre and Canapes” in a used book store, and when I opened it up, there staring at me in a great bold hand was the autograph of the man himself.

That same thing happened with my copy of Beard’s great memoir, “Delights and Prejudices,” which, providentially, I found in a junk shop in Portland, Ore., his hometown.

More often, though, I found the book and then collected the signature. At one point, I had so many signed firsts of Julia Child’s “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” that I was passing them out as thank-you gifts. Now I’m down to two — the regular edition and one specially published for a book club. They’re not going anywhere.

Some of my favorites are books by friends: Paula Wolfert’s “Couscous and Other Good Food From Morocco,” Thomas Keller’s “French Laundry Cookbook” and Sylvia Vaughn Thompson’s “Economy Gastronomy.”

Some are from authors almost no one has ever heard of: I’ve got a gorgeous signed limited edition from 1929 of Edward Bunyard’s “Anatomy of Dessert,” a British gastronome’s guide to the best varieties of fruit.

When I was just starting out in food writing, and much under the sway of M.F.K. Fisher, I lucked into a special slip-covered book club edition of her translation of “Physiology of Taste” — the one she wrote at the main library downtown. Years later a good friend took it along on a house visit and got it signed. (The price, $15, was still penciled in the front, prompting Fisher to remark acerbically after signing, “Well, it’s certainly worth a lot more than that now.”)

Some of my finds involved a bit of detective work. Marcella Hazan’s “Classic Italian Cookbook” became a classic when published by Alfred Knopf in 1976. But three years before that it had been published by Harper’s Magazine Press and had languished. Such are the vagaries of the book business, but to a collector and a huge fan of Hazan, it means something to have that scarce failed edition.

The personalities of the authors can affect the hunt too. Richard Olney is probably my favorite cookbook author, but he was a fairly unusual character, living most of the time in a primitive home in Provence. Needless to say, his signed books are scarce. It took years to turn up my copy of his “French Menu Cookbook,” and I paid for it through the nose. But I’ve never regretted the time spent — or the money.

And trust me, I wish I could say that about all of my decorating decisions.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.