A family business built on chili bricks

- Share via

After polishing off his French dip sandwich at Philippe the Original in downtown Los Angeles, Bert Muñoz redirects his attention to the meaty chili dripping down the sides of a 1950s-era melamine bowl and onto his cafeteria tray.

With quick flicks of his wrist, the chatty 37-year-old co-owner of Dolores Canning Co. scoops up brick-red spoonfuls without spilling even a drop onto his white knit shirt emblazoned with the company logo.

“I’ll walk by a hot dog stand and can tell it’s our chili just by the smell of it,” Muñoz says proudly of his bloodhound-like ability to ferret out the family’s product at Los Angeles-area street vendors and restaurants.

Over the years, he has tossed back plenty of bowls straight (competition lingo for all-meat, no-bean chili). Tasting his family’s spicy, ground beef-laden specialty is all in a day’s work for the sales manager of the East Los Angeles meat processing plant founded more than 50 years ago by his grandfather, Basilio Muñoz.

The brick is born

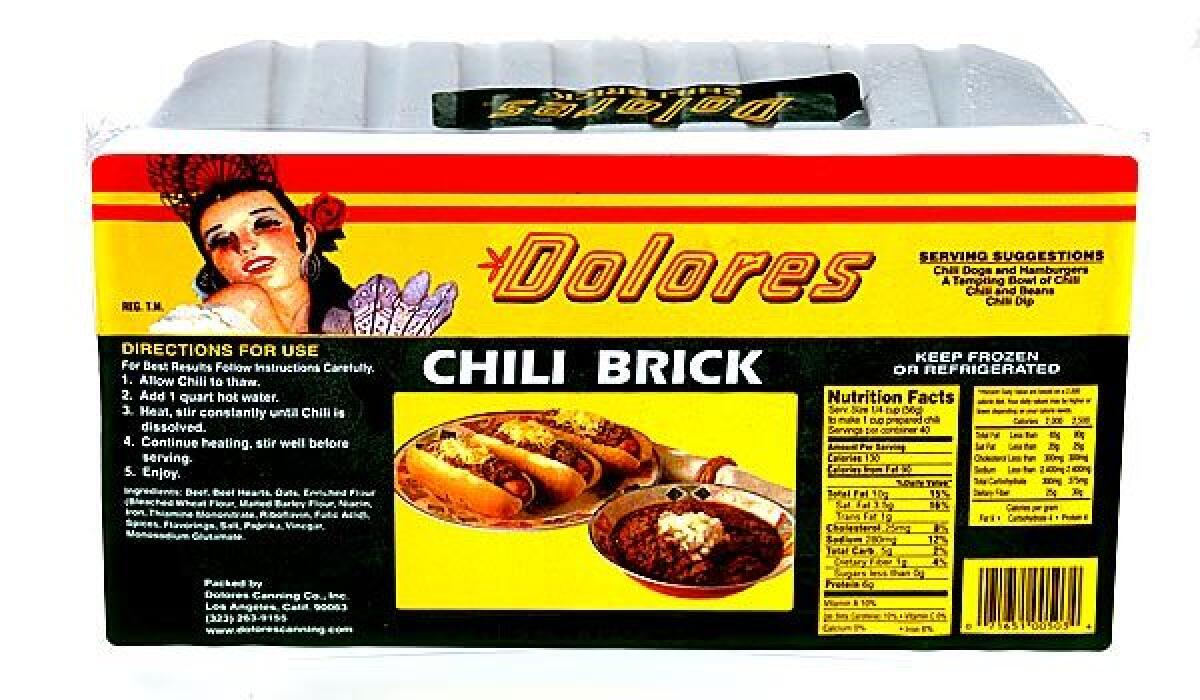

After building a successful business based on Mexican meats and prepared foods, Basilio and his sons Augustine, Frank and Steve introduced the Dolores Chili Brick in 1973.

“Grandpa started out distributing meat and canning menudo, but his baby project was to make chili that wasn’t canned,” Bert recalls of the company’s gradual shift from canned to frozen products including not only menudo (traditional Mexican hominy, tripe and calf foot stew), but also chili con carne. “With a frozen chili that’s concentrated, you get a fresher flavor.”

The unusual name, a reference to the chili’s shape when packaged and frozen, isn’t just a clever marketing gimmick. The term hails from the earliest dehydrated chili “bricks” made by Texas cowboy cooks around 1850. Drying a mixture of pounded beef, chile peppers and salt and shaping it into stackable rectangles that could be easily rehydrated with boiling water came in handy on Midwestern cattle drives and Gold Rush treks to California.

Today, Frank manages the company’s finances while Bert and his father, Steve, handle sales and purchasing. Bert’s 42-year-old cousin, David, manages factory operations and an aunt, Teresa, is the accountant (Basilio and Augustine, David’s father, died several years ago).

The family continues to package raw meat products such as carne asada (flank steak marinated with onions, vinegar and oregano) and produces a handful of jarred pickled products, including jalapeño-laced pork rinds and pig’s feet spiced with red chile peppers.

But the chili brick has been the focus of the business for as long as Bert can remember.

“By 5 years old we were in the spice room, 8 to 10 we were working in the kitchen, and by 16 we were driving trucks after school to make deliveries,” he says.

Bert and his cousin are the only grandchildren out of 10 to work in the family business. David suspects it has something to do with the rather unglamorous nature of meat processing. “ ‘Grandpa day care’ over Christmas vacation was driving all over Southern California to slaughterhouses.”

The chili is named after their grandmother, the woman with movie-star good looks on the company logo. The logo is based on a 1930s carnival painting of Dolores, flirtatiously fanning her face.

Putting it together

The family recipe is a traditional red chili made with paprika and chile pepper-spiked ground beef that is enriched with ground beef hearts to give it a more robust, meaty flavor.

According to the International Chili Society, the industry watchdog that regulates chili competitions, the Muñoz family’s all-meat chili would qualify for the competition circuit (chilies with too many added ingredients, such as beans, are frowned upon by chili fanatics).

But Bert and David are less concerned than the ICS about variations to their product.

“People doctor it up with whatever they like, serve it thick or thin . . . add onions, beans or even more beef to make it chunkier,” says David unapologetically. “We love to hear about that kind of thing.”

A scan of the company website with its somewhat unusual family recipes is evidence of that openness to culinary experimentation. There’s chili-sauced spaghetti, chili dip made with copious amounts of cream cheese, even a turkey and chili tamale casserole.

As for the Muñoz family’s personal taste, David is a devout Frito pie fan, the classic Texas snack of corn chips piled with chili and shredded cheddar, and Bert concocted his own variation as a student at Cuesta College in San Luis Obispo.

“I used to load up cases of chili for the frat house and we’d eat chili over steamed white rice all week. It’s still my favorite,” he says.

Even Philippe takes the liberty to make a few tweaks. “I tell customers they can buy the chili from Smart & Final, but they come back asking why it doesn’t taste the same,” says day manager Elias Barajas, who typically leaves out one important detail: Philippe uses beef stock rather than water to reconstitute the chili, giving it a richer flavor.

Because the product is so widely available at restaurant supply stores, keeping up with customers can be tricky. “Even we don’t know how many places use our chili,” David says.

That makes it hard to market the company’s other products, such as its carne asada, to customers who already use the chili. That’s when Bert’s nose for sniffing out chili comes in handy.

“I’ll sit down at a restaurant or go to a party and I can smell our chili on the stove,” he says.

But for this manufacturer, the ultimate badge of honor is kudos from a resident of chili’s birthplace.

“A woman in San Antonio orders our chili by mail,” he claims. “She says it’s better than what she can get in Texas.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.