How small Southern California fashion companies are staying afloat

- Share via

A recession can curb the urge to shop among even the most fanatical fashion devotees. Add unemployment (or underemployment) to the mix and, suddenly, high fashion nose-dives to the bottom of any priority list — hovering in importance near that $1,000 Italian espresso maker.

FOR THE RECORD:

Small design firms: A July 11 article about how local independent fashion companies are coping with tough economic times said that L.A. design firm Smoke & Mirrors moved from a rented space to be an at-home operation. The firm has since moved back to rented space in Los Angeles. —

Which is why the fashion industry has suffered so much since the onset of the recession. The total U.S. apparel market posted a 5.1% decline for 2009, compared with 2008, according to market research company NPD Group.

And while most big fashion brands boast the reserves to weather an economy that could only be described as shopper-unfriendly, small fashion companies have been going out of business left and right — including cult-favorite New York brand Phi and Chicago’s Maria Pinto, a favorite of Michelle Obama’s. Others, such as premium denim brand Rock & Republic, have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in hopes they can recapitalize.

But here in L.A., many small, independent brands are surviving (though sometimes just) by staying nimble, scrapping luxury-era business plans and rethinking what their customer wants, when she wants it and what she’s willing to spend for it.

Most agree that running an independent fashion company in this economic environment comes with a healthy side of uncertainty. “I’m still in business,” said Nony Tochterman, designer for contemporary brand Petro Zillia, “but going out of business has absolutely been a worry for me.”

Sluggish consumer spending means independent retailers are constantly at risk of having to close their doors. And when stores fold, brands with clothes hanging on the racks might not get paid. Although stores almost always pay upfront for clothes they buy from brands — putting the impetus on retailers to sell them — struggling boutique owners more and more often are asking brands to ship them clothes on consignment, so if they don’t sell the merchandise, they send it back to the brand unpaid. (Sometimes this arrangement originates with the brand, in an attempt to make the prospect of investing in the label less risky for the store.) But even if the merchandise is returned, the brand must find a new retailer for clothes that are no longer cutting-edge for the season and won’t fetch full price.

Case in point — Melissa Coker, designer for fashion-forward brand Wren, said she was never paid for the merchandise she had hanging in West Hollywood boutique Tracey Ross when it suddenly shuttered in late 2008.

“That really scarred me in a lot of ways,” Coker said. “Really, because of that, I started getting really strict about payment and realizing that if someone is giving you a million excuses for not paying, there’s probably a reason and it’s probably not a good one.” Coker now works with a retail service that does credit checks on retailers and would pay for any inventory a retailer could potentially shirk on.

Many indie L.A. brands say they’ve been working with their retailers to lower prices, which moves merchandise more quickly in the short term, but ultimately reduces profit for all involved.

One way L.A. brands have responded to retailers’ requests is by providing more current-season merchandise (a.k.a. “immediates”) that can be shipped to stores on demand. This way, spring merchandise is available in the actual season of spring, instead of months beforehand (which is the typical flow of merchandise deliveries), making shopping more time-sensitive.

Michelle Chaplin, co-founder of L.A. brand Smoke & Mirrors with partner and ex-”Project Runway” contestant Emily (Brandle) Harteau, said her business has shrunk to less than half the size it was before the recession, but she has managed to keep it afloat — in part — by selling immediates.

“Stores don’t know what six months will bring them, but they know what they have now,” she said. “So they say, can I get five of these, and five of these. It’s changed our relationship with our stores. They’re a lot happier with the merchandise and with us.” The altered modus operandi has paid off — 2009 was Smoke & Mirrors’ first profitable year in its three years in business.

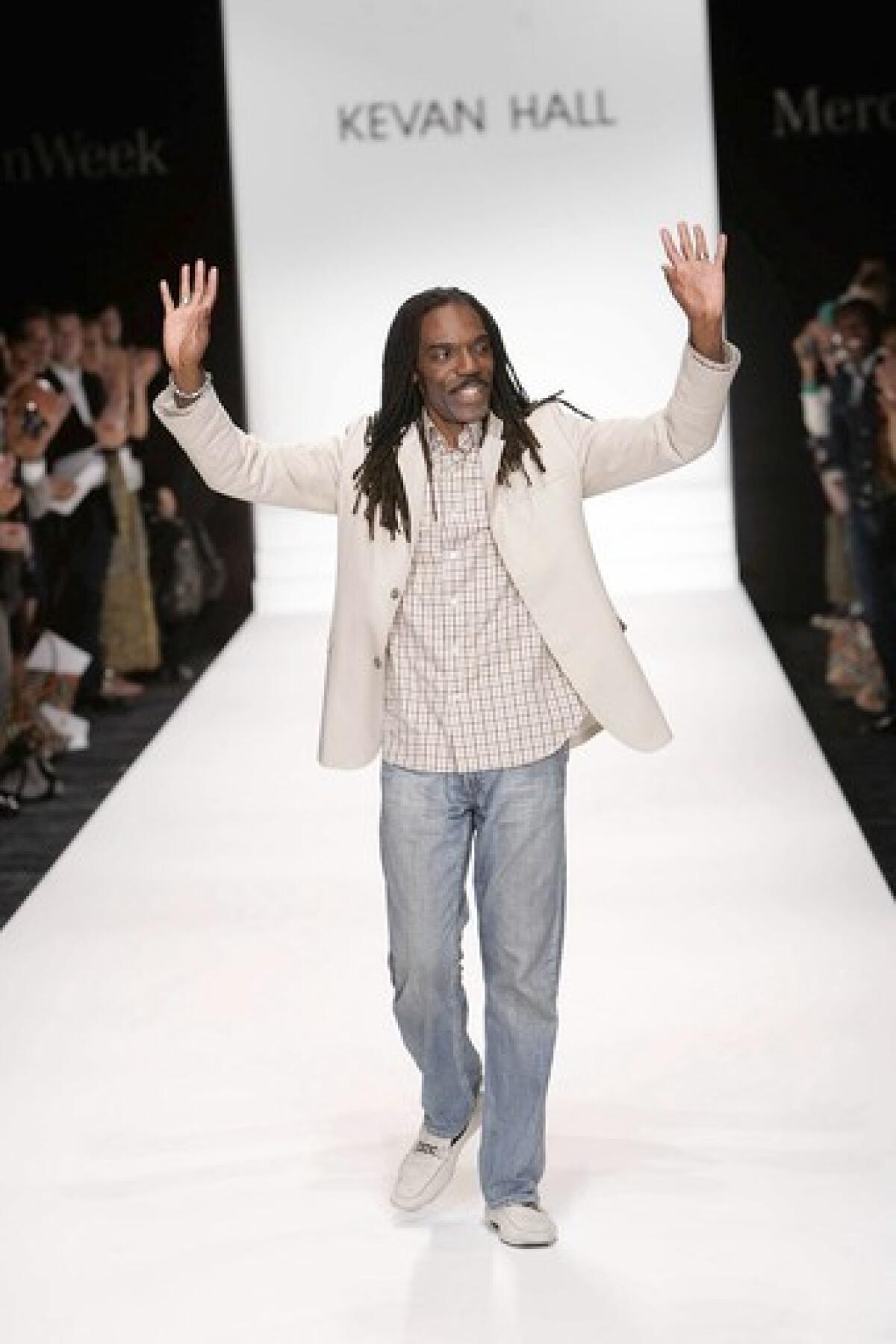

Cutting the fat out of the selling process has also meant, for some, removing the outside retailer from the equation almost entirely. Designer Kevan Hall, for instance, made a conscious decision once the recession set in to concentrate the bulk of his sales at his L.A. atelier.

“There are fewer stores to sell into and a lot of the stores are adjusting their price points and looking for products that are less expensive,” he noted. “So we’ve kept things flowing in the atelier, selling directly to clients.” And direct sales mean better prices for shoppers, because there is no retail mark-up.

Working one-on-one with clients, added Hall, has given him the opportunity to study what his customers are really looking for. “I think to myself, ‘Does a women really need this particular look or is this more of a fantasy piece? Is this a flourish or is this really going to end up being enjoyed?’ You always have to have some excitement in [collections] for editors, but I’ve just been focusing on what’s going to keep things flowing — to keep the doors open.”

For some local indie designers, downsizing their operations has been vital to survival. Chaplin and Harteau of Smoke & Mirrors, for instance, swapped their rented design space for an at-home office. And Coker, who launched her business in 2007, is more conscientious than ever about trying to accomplish as much as possible in-house.

“I’ve been super-conservative about not overspending,” she said. “It’s always important, but as a small new person it’s doubly important. It was like, ‘OK I’m not going to … hire expensive PR [public relations], get a huge studio, hire a bunch of people.”

Designer Gregory Parkinson said that though his stylish ready-to-wear business has changed “tremendously” since the recession, “We are able to make changes in a way a bigger company would find so much harder to do.” He cited quick deliveries, “convenient” flexible payment terms and more personalized attention as perks retailers enjoy with small, niche brands such as his.

Parkinson has also become creative when it comes to promoting his line. For example, instead of selling his collection through a traditional showroom (which typically acts as a sales intermediary for brands), he has begun showing his line directly to retailers in Paris, sharing costs with five other L.A.-based designers because “we were all fed up with showrooms. We wanted to cut out the middleman, who is no longer relevant.”

Corinne Grassini, founder and designer for the Society for Rational Dress label, credits the recession with forcing her to “play the game a little smarter,” which includes building better relationships with retailers, and brainstorming on the collection and selling strategies with her showroom and fellow designers. She added, “Everyone who has a job right now is working double the amount that they were before, myself included.”

Despite the longer hours and cutbacks, Grassini joins other local designers in saying the recession has brought out a scrappy resourcefulness in the way they do business that was lacking in boom times.

“These moments in time force you to be really creative,” noted Brett Westfall, designer for avant-garde label Unholy Matrimony and co-owner of the Case Study Unholy Matrimony boutique in Hollywood. “When you’re doing things on a strict budget, it’s harder. But think of it this way — instead of trying to spend a billion dollars on doing all this crazy stuff, you get to get back to the craft.”