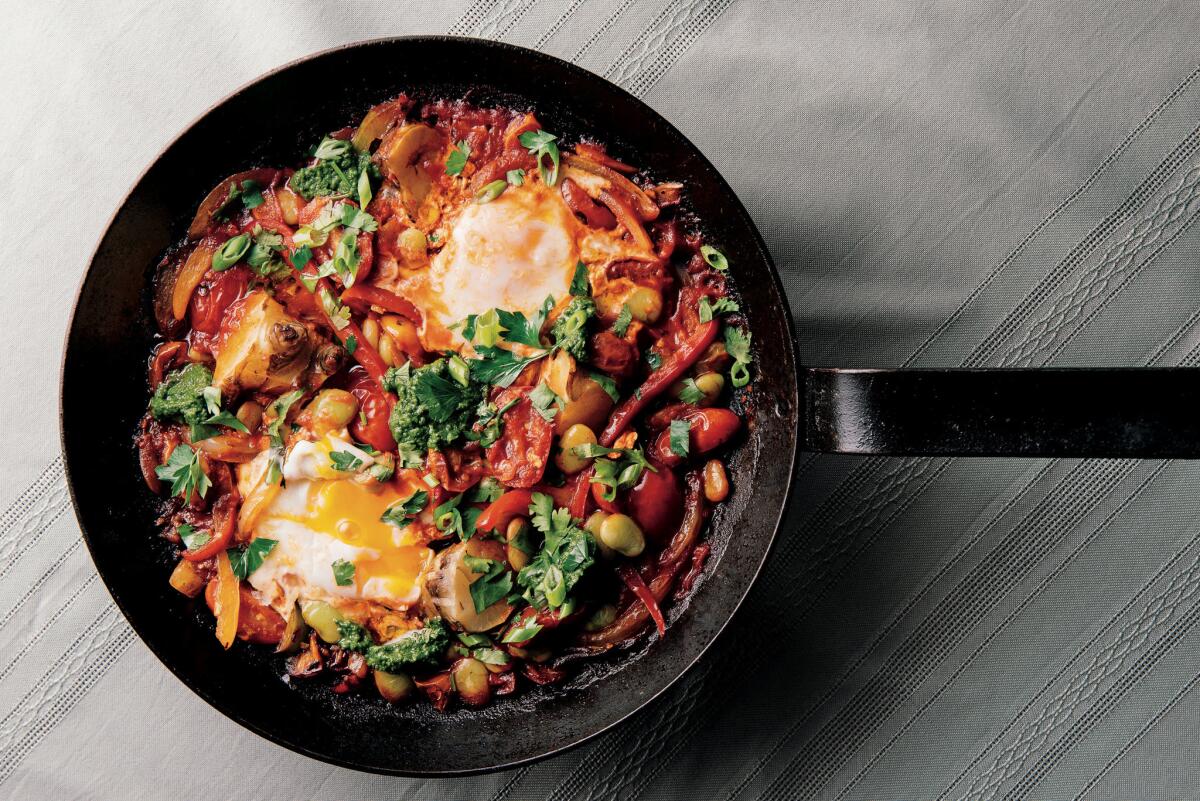

Q&A: An Israeli chef rediscovers his roots, plus a recipe for shakshouka

- Share via

Last year, at the Pebble Beach Food & Wine festival, there were two things that people seemed to be buzzing about: The first was the snack served by New Orleans-based chef, Alon Shaya: paratha topped with labneh, avocado, herbs and chicken marinated in the parsley, cilantro, serrano chile and allspice sauce known as zhoug. The second topic of discussion was Shaya’s new cookbook, which was published last month from Knopf, “Shaya: An Odyssey of Food, My Journey Back to Israel.”

What makes it a page-turner is that it’s more of an autobiography than just a greatest hits collection of Shaya’s recipes. In it, the Israeli-born Shaya tells his story, from latchkey kid teaching himself English by watching “Sesame Street,” to teenage waster saved by a no-nonsense Home Ec teacher, to a double James Beard award-winning rise — one for Best Chef South, one for Best New Restaurant — through the restaurant world.

Also included is a chapter in which Shaya and his former partner, John Besh, feed Hurricane Katrina victims and first responders by cooking up gallons of meatless red beans and rice.

Somehow reading about the two men, tirelessly problem-solving side by side, feels all the more mesmerizing because of what isn’t addressed in the book: Since last year, Shaya and Besh have been engaged in a complicated legal battle. After parting ways with the Besh Restaurant Group, he filed a lawsuit for the rights to his namesake restaurant, Shaya, the Israeli themed outpost of the three eateries — the other two are Domenica and Pizza Domenica, both featuring Italian cuisine — he developed with Besh at BRG. (The trademark dispute has not yet been resolved, which means currently a restaurant with his name on it operates without his involvement. Besh has also been the subject of sexual harassment allegations that are also unaddressed in Shaya’s book.)

Recently, when we spoke to Shaya while on book tour in Seattle, he was filled with enthusiastic talk, from the critical embracing of his 440-page, lushly illustrated cookbook to the food he’ll be serving in his two new restaurants, New Orleans’ Saba and one in Denver called Safta. “We’ve learned a lot over the past several years,” he said. “This is going to be our best work yet.”

Which came first, the memoir or the recipes?

When I sat down and began writing the book I really didn’t know how I was going to get my life of recipes into a cookbook that would make sense to people. I was born in Israel. I’ve been fortunate enough to live in Italy, in the South, in Vegas, in St. Louis. I thought, “How does that all come together? How do hummus and gnocchi go into one book that anyone will care about or want to read?” So I started writing my life story and I began to see that the book was going to be a series of stories, and from there I decided what the recipes for that story should be; the recipes were almost secondary.

Any surprises during the research phase?

I found out that my mom never wanted to move to America. My father moved here a couple of years before we did so he could save money to fly us out. When I started talking to my mom for the book, I asked her about her life in her 20s. She told me she was very happy in Israel and the only reason she came to America was because my father wanted all of us to move here. I never knew that before.

Walk us through an early kitchen memory.

I was very independent from a very young age — from the age of 5 on. My mother was raising us by herself, working her butt off to keep a roof over our heads. She’d arrange for a taxi cab to pick me up from school every day and take me to daycare and then home because she couldn’t get out of work. I was always home for a few hours by myself. By the second grade, I was grocery shopping for the house. Then I’d come home and start cooking. I once saw my teacher while I was filling the cart and she was like, “Where’s your mom?” and I said, “Oh, she’s at work. I’m just getting groceries for the house.” Today, it would be a disaster. What’s an 8-year-old doing grocery shopping by himself?

What were some of little Alon’s culinary creations?

I wasn’t roasting chickens. I was just throwing together whatever I could. I’d scramble eggs; I’d put potatoes in the microwave with cheese. I’d take already-cooked things out of the refrigerator and mix them together — like leftover mashed potatoes with Israeli salad on top. That combination is something that even today I crave. As I got older, I started doing more elaborate stuff. By the time I was 13, I was already working in food service. I was just fascinated by food.

“Shaya” starts out with a Proustian moment: You come home from school and smell your visiting grandmother making a Bulgarian pepper spread called lutenitsa.

That smell of roasting peppers and eggplants over the flame always stuck with me. Every time I smell that I think of my grandmother, of a sense of home and normalcy. Then I spent the next 30 years trying to focus on Italian food.

Why?

At the age that I came [to the United States], I didn’t want anything to do with Israel. I didn’t want to be different; I wanted to be American. So subliminally I think I did everything I could through my childhood to push that away. I had an inclination when I started cooking Israeli food again about why I was doing it — but when I started writing it all down, it kind of opened my eyes to all that. It was a very emotional experience.

When did that reconnection first take place?

In 2011, I went to Israel — this is already after Hurricane Katrina, after living in Italy, after opening Domenica. I’d grown a lot as a chef and had confidence in the food I was cooking, but I still wasn’t connecting with the food of my heritage. I was walking through the Carmel market [in Tel Aviv], there was the smell of the vegetables cooking over coals, and all those spices, and I heard some old ladies speaking Hebrew to each other and it just kind of hit me at that moment that this was who I was, this is where I was from. I thought at that moment, “What if my dad never wanted to move to America? What if we stayed in Israel? Would I still be a chef? Would I be cooking Italian food? Would I be cooking this stuff?” I didn’t know. And I realized that it was something that I needed to begin embracing — and I finally felt confident enough to do that.

Was there any trepidation about introducing dishes like shakshouka or kibbeh nayeh to New Orleans?

At the time, I didn’t think New Orleans was ready for Israeli food. Like it was a little too farfetched. The first thing I put on the menu after that trip to Israel was whole cauliflower [roasted in an 800-degree pizza oven]. It got rave reviews, everybody loved it. But I was passing it off as Italian food. I’d make hummus and call it ceci purée. But the more people liked it, the more confident I became. Eventually I felt like I needed to open Shaya so I could have an outlet for that food.

Let’s talk about your new restaurant, Saba, which opens in New Orleans at the end of April. Will the menu be similar to Shaya?

We’re definitely not just copying and pasting. What we’ve cooked in the past is just the tip of the iceberg of what Israeli cuisine is. We’re going to have a charcoal grill where we’ll be cooking stuff over coals with skewers. There will be octopus with shawarma spice, my grandmother’s lamb kebabs over charcoal. Our friend Grasion Gill has a bakery called Bellegarde Bakery. He’s sourcing wheat from all over the country and milling it fresh using a big stone mill. So we’re going to make our pita with fresh-milled wheat, which I’m super psyched about.

The Katrina chapter. Was there ever a conversation with your editor about taking it out of the book because of your severed ties with John Besh?

I think the beautiful thing about the book is that they are true depictions of my moments in life at those times. The book had to be honest and thorough because I knew that’s what would make a difference for people when they read it. That it wasn’t watered down at all. The stories are the stories; the history is the history. And the journey continues. We’re very much looking forward to the future and everything we have coming up. Life is life. You have to take the opportunities as they come and you have to make the most out of every situation and stay positive through it.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.