Obama’s action on immigration leaves millions still facing deportation

- Share via

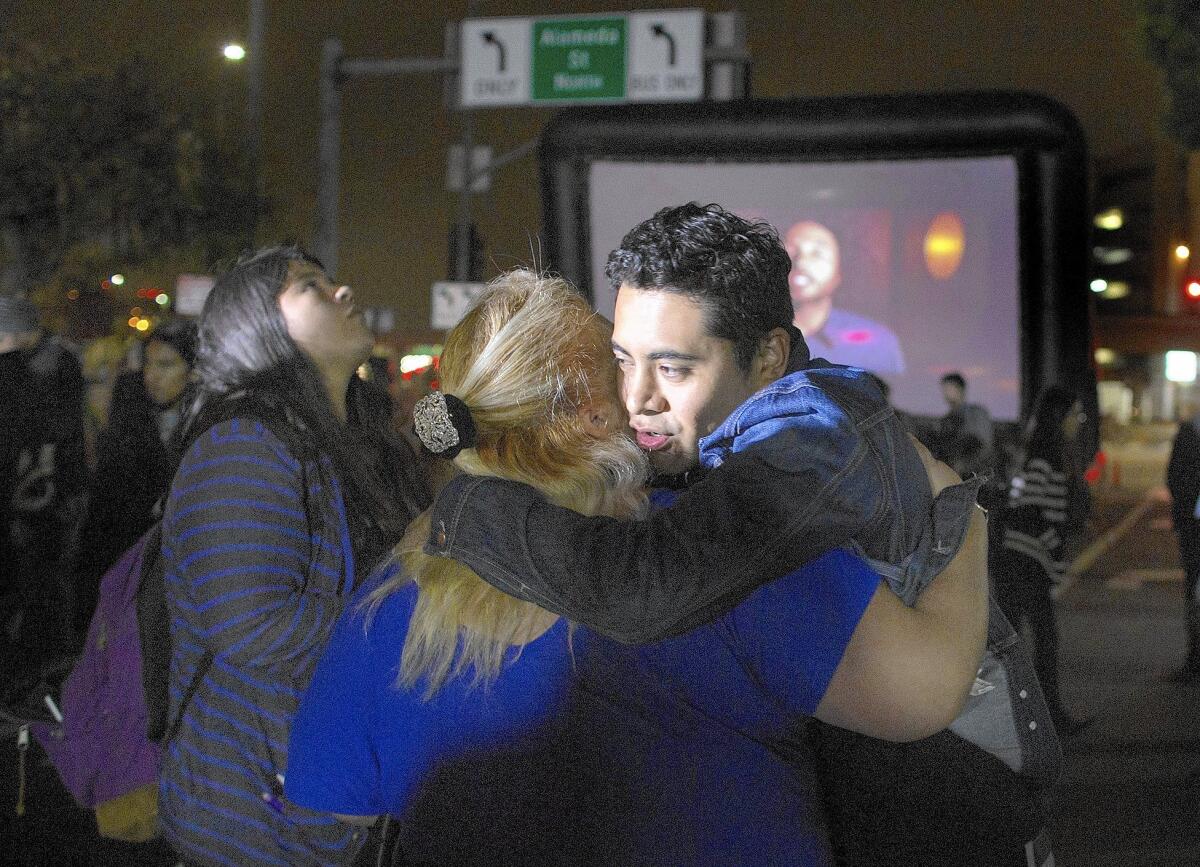

Minutes after Armando Ibañez heard President Obama tell the nation that millions of people in the country illegally would be allowed to work and live openly in America, the 32-year-old excitedly scrambled to call his aunt, uncle and friends to deliver the good news: They would finally be shielded from deportation.

But with every call he made he held back tears, knowing he and his mother wouldn’t benefit under the new policy. They’d continue to live in the U.S. with the fear of deportation hanging over them.

“I’m going to be left behind?” Ibañez said. “I feel like living in fear is the price that I’m paying for the American dream.”

Although Obama changed the lives of about 4 million people living illegally in the U.S., millions more will see no benefit from his executive action, which he said will keep families together by temporarily protecting a large number of parents of U.S. citizens or longtime permanent residents.

Ibañez, who entered the country illegally 14 years ago from Mexico, is one of roughly 6 million people living without legal status in the U.S. who won’t qualify.

Under the changes, about half of the people in California who are in the country without authorization are now eligible for relief, according to a report released Friday by the Pew Research Center. But that leaves well over 1 million people without protection.

“We’re leaving behind not only people with long ties to the United States but also vulnerable people,” said Royce Bernstein Murray, director of policy at the National Immigrant Justice Center. “We are celebrating this as a victory because we know it’s going to help a lot of families come out of the shadows and live without fear, but we are really mindful that there are deserving folks who are left out.”

The policy leaves out many of those who have lived here for some time but don’t have children born in the U.S., for example, as well as those who would otherwise qualify but left the country even briefly at some point in the last five years.

It also excludes some of the most marginalized — such as a recent influx of unaccompanied minors from Central America and many members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community who are in the country without legal status.

“The idea of someone being deserving, especially if they have children, we think is preposterous,” said Hairo Cortes, an organizer with Orange County Immigrant Youth United. “What about the LGBT undocumented community? What happens to them? Most don’t have children. Are we going to penalize them for that?”

There are at least 267,000 LGBT people in the country illegally, according to a report by The Williams Institute, a gender identity and sexual orientation think tank based at UCLA.

Johanna Saavedra, who fled Mexico 17 years ago because she said she was persecuted for identifying as a transgender woman, said she’s tried applying for immigration relief but has been scammed out of money twice by unscrupulous attorneys. She’s trying with a third but knows that she can be targeted for deportation at any time.

“It’s difficult enough being a transgender woman, but it’s even harder when you don’t have the legal status and papers to work legally in this country,” said Saavedra, a hairdresser from North Hollywood.

Also excluded from the new policy are the tens of thousands of Central Americans who illegally crossed the U.S.-Mexico border as part of a mass exodus

over the late spring and summer.

Many of them were fleeing violence and have legitimate claims to stay in the country, said Judy London, directing attorney of the Immigrants’ Rights Project at the pro bono law firm Public Counsel in Los Angeles.

“We represent hundreds of children detained at the border,” she said. “We’ve yet to interview one child who is coming for an immigration benefit. They’re all running for their lives.”

Although Obama made it easier for certain recent graduates in science and technology to work here, he did not grant special protections for other workers, such as farmworkers.

Juana Sanchez, 45, who came to California illegally from Mexico 15 years ago to pick grapes, potatoes and peppers in the Central Valley, said she had hoped for special protections for farm workers.

“We work long hours in the freezing cold and hot sun for very little money,” she said. “We deserve it.”

She will probably qualify for protection under Obama’s plan because she is the mother of two American-born children. But she is unsure whether her husband, whom she married in June and is not the father of her children, will qualify.

“I feel happy on the one hand,” she said, “but there are a lot of people who work in the fields who don’t have children who were born here who are being left out.”

Leo Chavez, a professor of anthropology at UC Irvine, said a similar divide happened after the 1986 immigration overhaul under President Reagan.

An estimated half a million people who didn’t qualify under Reagan’s program are still living in the country without legal status, according to figures provided by the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank that studies the movement of people worldwide.

Many of them are still toiling in low-level jobs because they don’t have authorization to work, he said.

“They don’t have much future or mobility. They’ve pretty much been stuck.”

In many ways, Erika Aldape fits the profile of a person who could qualify for immigration relief.

Brought to the U.S. from Mexico by her parents at age 7, she has no criminal history and was a model student, a member of the honor society and the Student Council.

But Aldape, 24, was not eligible in the first round of Obama’s deferred action program, and again is not eligible for the program the president announced on Thursday.

Recipients for the new deferred action program must have been in the U.S. since 2010. Aldape went back to Mexico for several years for college, returning to her family’s home in Indiana with a degree in international business in 2011.

When she heard that she was being left out, again, “I just kind of lost it and broke down and cried,” she said. “It’s just hard that pursuing my education would have all these negative effects on my life.”

Her two brothers qualified for Obama’s first deportation deferral program, in 2012, which extended temporary protection to certain young people who were living in the U.S. illegally after being brought to the U.S. as children. They are now working good jobs while she is tending bar in a Mexican restaurant.

“It’s not fair,” she said. “They’re kind of leading normal lives now.”

Twitter: @thecindycarcamo

Twitter: @katelinthicum

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.