Higher Learning: Efforts to expand California university systems are growing

- Share via

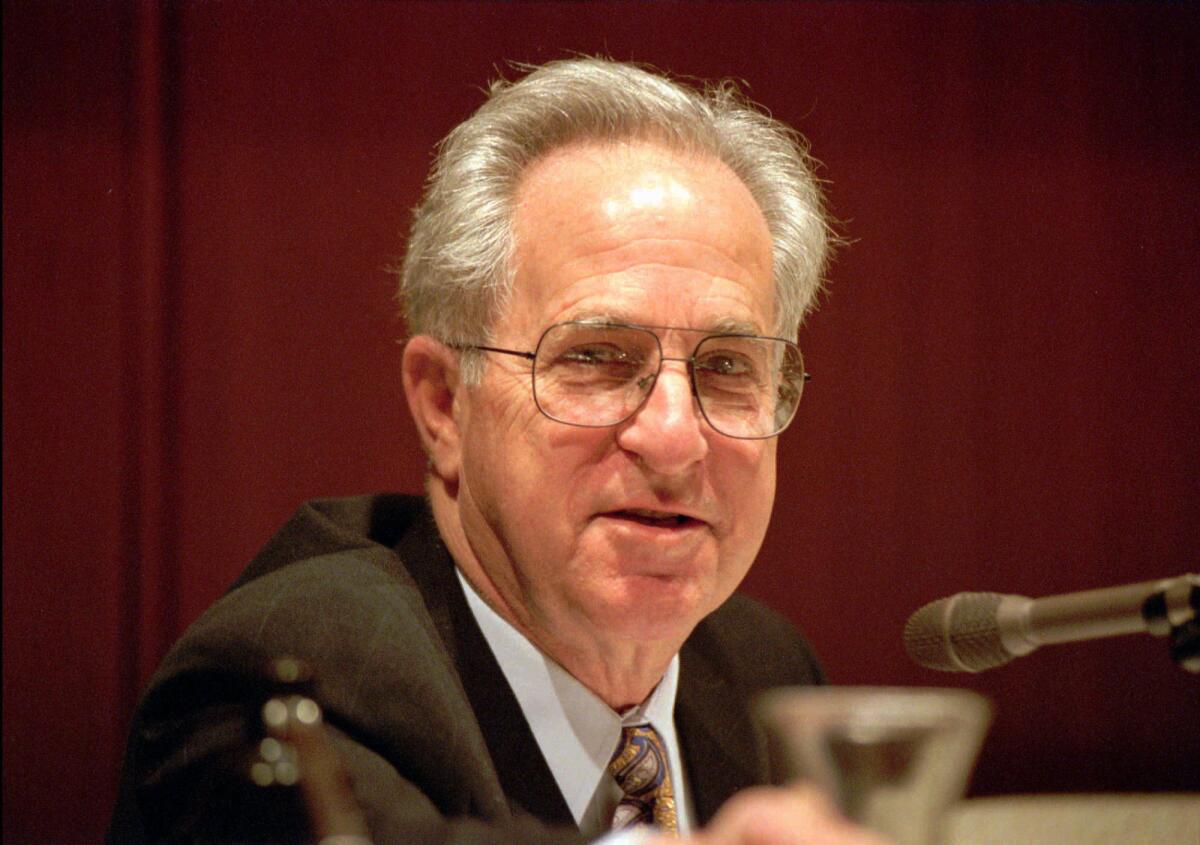

The death last week of former University of California system president and UC Irvine chancellor Jack W. Peltason at 91 elicited warm memories of the modest political scientist who achieved high positions in American academia without losing his sense of humor. He also was known for his role in helping to build new university campuses from scratch and growing them to maturity.

At UC Irvine, which accepted its first students in 1965, Peltason hired many of its first faculty and later directed a massive expansion of the campus and its programs. Then, during his three-year UC system presidency, Peltason oversaw the difficult off-again, on-again search effort that in 1995 selected Merced as the site for UC’s 10th campus; 10 years later, despite environmental and money problems, UC Merced opened.

Coincidentally, Peltason’s death came as some in California’s higher education circles again are talking about what had been unthinkable during the Great Recession. Even as arguments continue about proposed tuition increases and limits on state funding, a variety of new proposals are aimed at increasing the capacity — and number — of public universities to enroll more students.

UC Merced officials last week pitched to the UC regents a plan to increase its student body to 10,000 from 6,200 over the next five to seven years and construct many buildings to double the school’s physical capacity. The regents seemed nervous about the details of financing, which could approach $1 billion, but were receptive to accommodating more eligible applicants who are feeling shut out of UC.

UC Berkeley is advocating a major new satellite campus on the underused 130 acres it owns seven miles away on the Richmond waterfront; leaders envision new programs there in partnerships with international colleges for as many as 10,000 faculty and students within 40 years.

And state Assemblyman Mike Gatto (D-Glendale) recently attracted attention for proposing a new UC campus, possibly near Silicon Valley or Los Angeles, devoted to technology, science and some arts. Gatto’s legislation would push a feasibility study for “a public version of Caltech” and provide $50 million for land acquisition and initial building.

Meanwhile, for the Cal State system, Assemblywoman Susan Talamantes Eggman (D-Stockton) in December introduced a bill that would initiate a study of a possible Stockton campus, which would be that system’s 24th school. Elsewhere, hometown civic boosters are advocating for one in Chula Vista, near San Diego.

Critics say it is foolhardy to talk about new UC or Cal State schools at a time when existing campuses are struggling to maintain what they now offer and students face tuition increases. It would be better to first schedule more classes on weekends, nights and summer breaks before any construction is considered, they say. And increased online education provides a more economical and democratic way to expand education, they add.

However, in an interview this week, Gatto held to his view that the state must act now to educate bright young people and keep their talents in California. Online education can help on the margins, he said, but is not stimulating enough to fully engage university students. And even Merced’s proposed expansion will not be big enough to solve the problem because more crowded campuses like UCLA have little or no room to grow.

With the state treasury showing significant surpluses, he said, “there is no better place to spend this extra money than on long-term higher education planning.” It’s time, he said, to act like Peltason and other education leaders of a past generation. After all, he said, “Irvine was once orange groves.”

California is unmatchable in its history of higher education expansion. The mid-1960s saw UC San Diego, UC Irvine and UC Santa Cruz open, and 40 years later came Merced. The Cal State system added the San Marcos, Monterey Bay and Channel Island campuses between 1990 and 2002. Over the last decade, five community colleges, most recently Norco and Moreno Valley in the Riverside area, brought the total to 112 statewide.

Robert Shireman, executive director of California Competes, a higher education policy think tank in Oakland, said the initial high costs of establishing UC Merced — about $500 million — still has some officials skittish about opening new campuses while existing ones are strapped for money. Gatto’s proposal, he said, would require “heavy lifting.”

More likely, he said, are expansions at existing locations, including Merced, and satellite facilities, such as UC Berkeley’s plan for its Richmond Field Station, that don’t require a complete new administration.

But Shireman said new campuses might be possible again after 10 years or so “if the economic boom continues.” It would be more likely to be within Cal State, which does not require as many labs and research facilities as UC, he said.

UC’s Peltason was eulogized this week as a pioneering campus builder, but a closer examination shows that even he was a cautious and worried expander.

At one point in 1993, concerned about finances, he suspended the search for a San Joaquin Valley location. Then two years later, even during celebrations of Merced’s selection, Peltason sought to dampen expectations. In a comment that echoes the current debate, he said more funds were needed first “to stabilize the campuses we have.” As for Merced, he added: “We know it’s not realistic to go asking for the money now.”

Twitter: @larrygordonlat

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.