Great Read: Boyle Heights girl aims for more, with help of soccer

- Share via

Luisa Hilario’s ponytail swings from side to side as she races for the train.

“Hurry!” yells her mother. “We’re going to be late.”

Luisa carries her soccer ball and cleats. Her little brother, the first-aid kit. Her mother, Erika, the ice chest, blanket and chair.

Most weekdays, they commute for five hours round-trip — by train, bus and on foot — from Boyle Heights to northeast Pasadena so Luisa can play. The 11-year-old plays for one of California’s most elite soccer clubs. Someday, she hopes to compete professionally.

But the family doesn’t hustle for the sake of soccer. They hustle for a glimpse of another world.

In Pasadena, Luisa plays alongside the children of doctors, lawyers and professors. Her teammates arrive at the field in air-conditioned cars from La Crescenta, San Marino and Glendale. They chitchat about dream colleges and vacations abroad and pretty houses with big backyards.

Erika cheers on her daughter, in Spanish, from the sidelines: “You can do it, Luisa!”

You can aim for more.

“I don’t know exactly what that means,” Erika says. “But it’s something big, and we’re not going to rest until she gets there.”

::

Eight years ago, Luisa’s father began to work as a long-distance truck driver. They got by, day to day, on what he made.

Then last year new regulations caused Luis Hilario to give up his truck, and he had to declare bankruptcy. He’s bounced from job to job since, trying to find a steady paycheck. He comes home four nights a month, at most.

At home, Erika’s focus is Luisa and her 8-year-old brother, Erick. They live in an apartment not far from the Gold Line. It’s a dark, run-down, Spanish-style building in an area where many landlords have been begun trying to force people out with higher rents.

But Erika refuses to settle. She painted the walls deep blue, yellow and green, and placed her Virgen de Guadalupe statue in the hallway cove and her two parakeets in a cage out back. She installed ceiling fans so when it’s hot, the kids don’t have to open the windows and smell the marijuana smoke outside.

At 34, she’s the kind of woman who hardly pays attention to herself: frizzy hair tossed back in a bun, old sweatpants and dark circles under her eyes.

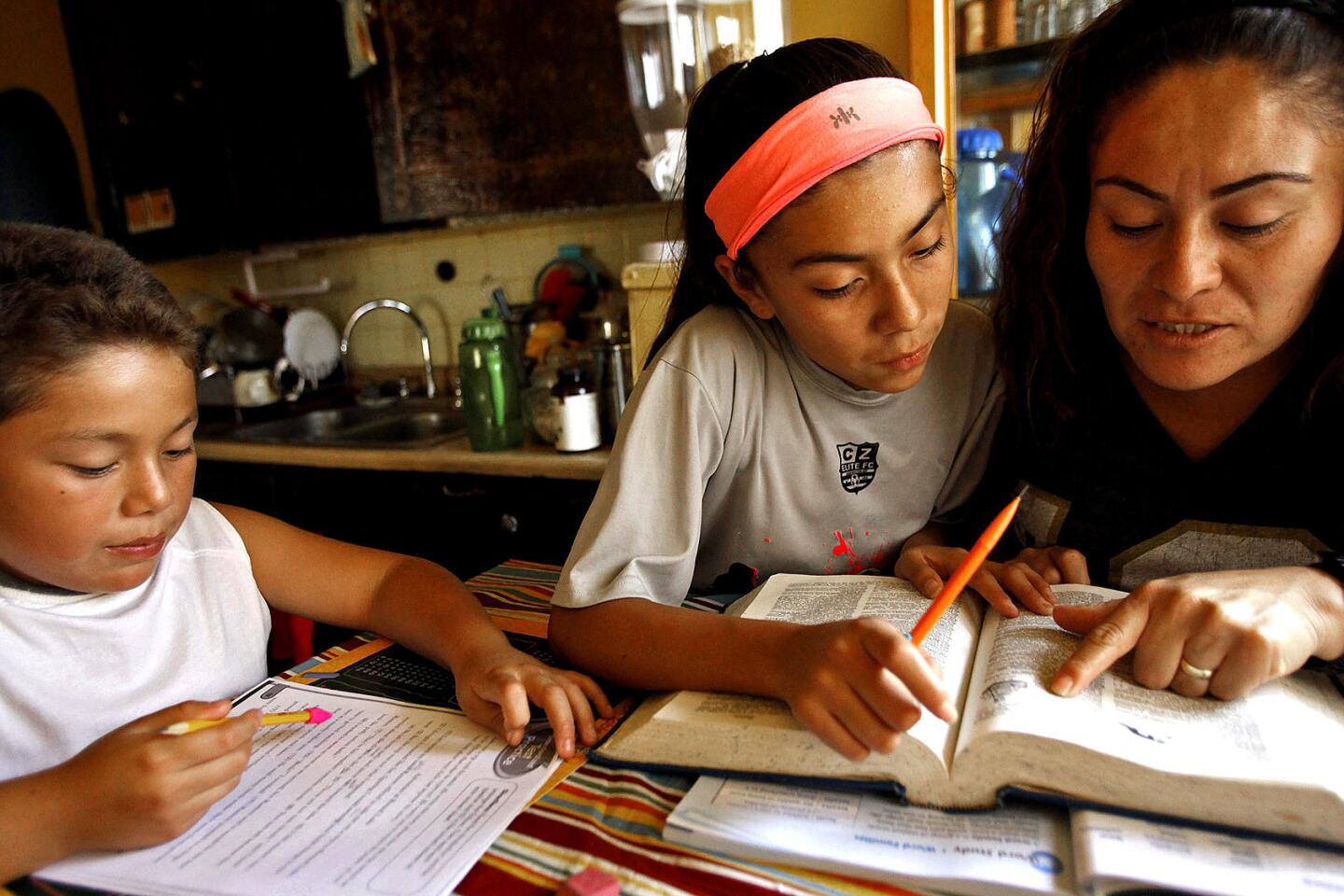

But she runs her house like an Eastside “tiger mom”: Luisa’s three dozen soccer trophies and medals line the entertainment center like shiny soldiers. School and library schedules hang from a bulletin board. Multiplication tables are taped to the wall in front of the toilet. Next to Luisa’s desk hang two wooden signs with the definitions of the words joy and inspire.

On Friday nights, Erika pulls out a whiteboard and transforms the living room into a classroom for Spanish lessons. She wants her kids to speak both languages perfectly.

Any time there’s extra money, it goes to enrich the kids: Jujitsu practice. English tutoring. Swimming lessons. She hopes one day to squeeze in art and music.

Every day, Erika preaches one lesson: Don’t take no for an answer.

Years ago, when Luisa was in kindergarten and bullied to tears daily because of her severely crooked teeth, Erika complained to the principal. When nothing changed, she pulled Luisa from the public school and enrolled her at a private one nearby.

There was no money for tuition, and she knew her husband would disapprove. So she didn’t tell him. Instead, she negotiated a discount at the school and for months bought only the bare necessities to get by.

“Sometimes I think I’m crazy,” Erika says. “But when it comes to the kids, there are no excuses.”

She hustles to stay afloat. They all do.

Erick collects recyclable bottles and cans during soccer practices and games. Luisa makes colorful flowers out of duct tape to sell at school for $1. Erika hawks bracelets, purses and hair bows she buys on the cheap in L.A.’s fashion district.

Occasionally friends help her pick up a day of work counting tortillas on an assembly line — so long as it doesn’t clash with the children’s schedules.

::

On a recent afternoon, the trio waited for the bus near the 210 Freeway overpass at the Sierra Madre Villa station. Luisa slipped on her cleats and adjusted her pink hair band. She’s a friendly girl, but rarely smiles.

When talk turns to the possibility of braces, her eyes light up. At school, she said, they announced that a few students would be given free ones.

“I really, really hope it’s me,” she said. “If it’s not me, I really hope they go to someone who deserves them.”

The following week, when she found out she wasn’t chosen, she was crushed. Erika tried to cheer her up on the walk home from school. “Luisa. Maybe God knows something we don’t know. What if your teeth are your secret power and they take it away?”

Focus on the prize, her mother tells her.

Luisa’s days stretch from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. She eats her dinner, does her homework, tries to nap, all on the train.

She has a 4.0 grade-point average. When you ask where she plans to go to high school, she names two elite private ones — Flintridge Sacred Heart Academy in La Cañada Flintridge and Harvard-Westlake in Studio City.

How she’ll get there, she has no idea. There’s no train in those directions and her mom doesn’t know how to drive. (A teammate’s mother gave Erika an old van, but repairs are costly so it’s collecting dust outside their apartment.)

But if they manage to get to soccer games in far-flung places like San Francisco and San Luis Obispo by Greyhound, they can manage to get to high school each day, Erika says.

Luisa’s sights, for now, are set on using soccer to get a full-ride high school scholarship.

“I just have to push myself,” she said. “A lot of kids in Boyle Heights never have a chance to leave the area at all. I have, so I have to set an example.”

When she plays, she loses herself in the game. Her worries seem to fade away.

“Everything I’m feeling,” she said. “I leave it out on the field.”

Her coach, Cherif Zein, said it’s up to Luisa to determine how far she will go. The tough-love mentor with a gravelly voice has seen thousands of kids come through in 39 years of teaching soccer with his club, CZ Elite FC. Many of his players have gone on to compete on the collegiate level and for national teams, in the United States and abroad.

Luisa’s skills as a defender are solid, he said — good enough that when the team went to Costa Rica for a tournament last year, her travel expenses were paid.

As Zein rounded up the team for drills, the sixth-grader was among the first at his side.

“OK, Luisa!” he yelled, kicking the ball her way. “Show me what you got!”

She adjusted her footwork with clean, calculated moves and zeroed in on the net.

“Goooal!” Zein yelled, raising his hands.

Erika looked on from her folding chair, the ice chest full of bananas by her side. She was beaming.

“On the field, they’re all the same,” Zein said. “It doesn’t matter how much you make or where you live or who you are. It’s them and the ball and nothing else.”

Perhaps that’s why Luisa loves the game so much.

esmeralda.bermudez@latimes.com

Twitter: @LATbermudez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.