In creating a haven for artists, Ghost Ship operators built a deathtrap, prosecutors allege

- Share via

Reporting from Oakland — Derick Ion Almena and Max Harris took over the aging warehouse in Oakland with hopes of creating an affordable space for artists and musicians to live and work in the Bay Area’s overheated housing market.

But prosecutors said what they actually created was a deathtrap.

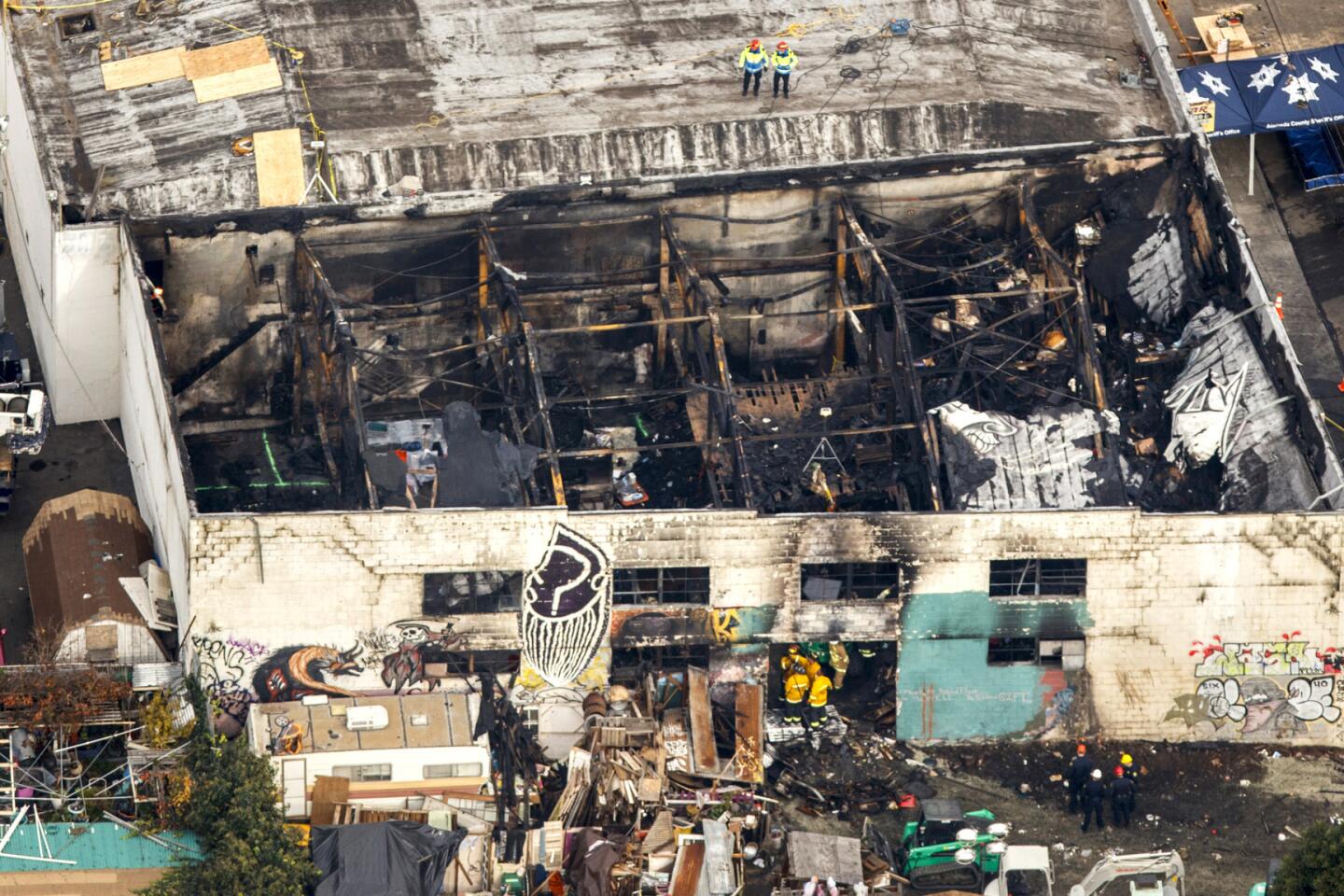

Almena, the manager of the so-called Ghost Ship, undertook a series of unregulated construction projects that turned the industrial space into illegal dwellings, charging residents $300 to $1,400. Authorities say the men filled the building from “floor to ceiling” with tapestries, pianos and furniture, turning the Ghost Ship into a tinderbox.

On Dec. 2, 2016, nearly 100 people piled into the warehouse for a concert, and Harris, the venue’s “creative director,” blocked off a stairwell that served as a secondary exit, authorities said. So when a fire began burning through all the debris, prosecutors allege, concertgoers and residents had only one way out — a narrow, rickety staircase. Thirty-six people could not make it out and died in one of the deadliest fires in modern California history.

Alameda County prosecutors capped a six-month investigation into the deadly blaze on Monday when they charged Almena and Harris with 36 counts of involuntary manslaughter, saying their management of the Ghost Ship was not simply negligent, but criminal.

Dist. Atty. Nancy E. O’Malley said Monday that Almena and Harris “knowingly created a fire trap, with inadequate means of escape…. They then filled that area with human beings.”

Prosecutors said both men repeatedly lied to police when asked if anyone was living inside the Ghost Ship, and neither outfitted the building with fire suppression equipment or smoke alarms. Several people had warned Almena of the “obvious fire hazard,” according to the court filing.

The Ghost Ship fire sparked crackdowns on illegally converted warehouses across California and shed light on the struggles of artists to afford rent in big cities like San Francisco, Oakland and Los Angeles.

It also created a scandal at Oakland City Hall amid revelations that residents and neighbors had complained for years about dangerous conditions at the warehouse without much action from city officials.

The criminal charges come amid continued questions about why the city didn’t do more to close the Ghost Ship and what actually caused the fire.

Investigators from the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives spent weeks combing the charred husk of the warehouse, but much of the evidence they would have needed to determine a cause was swallowed by flames, prosecutors said Monday.

Almena’s attorneys — Jeffrey Krasnoff, Kyndra Miller and J. Tony Serra — have previously said they believe the fire started in an adjacent building and spread to the Ghost Ship. They have also argued that the agencies investigating the fire have a “conflict of interest” because they are also defendants in wrongful death suits brought by the victims’ families.

“We believe that these charges represent no less than a miscarriage of justice, and we are confident that this attempt to make a scapegoat out of our client will fail,” the attorneys said in a statement.

Almena made a brief appearance Monday afternoon in a Lake County courtroom following an arrest. He was held on $1 million bail. It was unclear whether Harris had legal representation.

Both men face 39 years in prison if convicted, according to Alameda County Assistant Dist. Atty. Teresa Drenick.

Almena, 47, was the subject of intense criticism in the wake of the blaze, with many current and former tenants telling news outlets he knew of the squalid and dangerous conditions inside the building but failed to address them.

He bristled at the idea that he was responsible for the fire during an interview with NBC last year.

“I’m incredibly sorry and that everything that I did was to make this a stronger and more beautiful community and to bring people together,” he said at the time. “People didn’t walk through those doors because it was a horrible place.”

Public records released in February showed the warehouse had been subject to at least 10 code enforcement complaints and that city officials had visited the building numerous times, but failed to go inside.

Shelley Mack, a former tenant who moved out before the fire and provided investigators with her account of conditions inside the warehouse, said she was relieved that criminal charges were filed, but believes there is still plenty of blame to go around.

Almena took out a five-year lease on the building in November 2013, and quickly began to use it as a rental space, despite the fact that the warehouse was not zoned for residential use, according to a probable cause statement filed Monday. Almena also moved into the building with his wife and three children.

He soon “encouraged tenants to use non-conventional building materials” to create their living spaces, according to the court filing. Much of it was flammable and probably served as kindling during the fatal blaze.

“Almena substantially increased the risk to those living, working or visiting the building by storing enormous amounts of flammable material inside the warehouse,” the court filing read.

On the night of the fire, Harris’ decision to block one of the warehouse’s two exits proved disastrous, prosecutors said. The building’s power failed shortly after the fire erupted, leaving those fleeing to navigate a darkened, rickety, wooden staircase, which some witnesses compared to a “gang plank,” as they raced for safety.

All 36 victims died of smoke inhalation. They ranged in age from 17 to 61.

We continue to mourn the loss of the 36 young and vibrant men and women, 36 members of our community who should be with us today.

— Alameda County Dist. Atty. Nancy E. O’Malley

“We continue to mourn the loss of the 36 young and vibrant men and women, 36 members of our community who should be with us today,” O’Malley said.

It remains unclear whether anyone else will face charges in the blaze, including building owner Chor N. Ng. Asked if the investigation was closed, Drenick said the district attorney’s office would comment only on the charges filed Monday.

Ng’s attorney declined to comment.

Almena and his wife, Micah Allison, have been described as wanderers who once organized their lives around eccentric festivals like Burning Man in the Nevada desert. He was convicted of receiving stolen property in 2015 and is on probation until 2019.

Harris, a 27-year-old tattoo artist who also went by the names “Max Ohr” and “Warlord,” lived in the structure. He previously told the East Bay Times that he reported problems with the warehouse’s electrical system to the property owners.

Harris sought financial aid on social media in the weeks after the fire, while openly musing about creating a similar creative space somewhere else.

“In no way do I mean to take away from the tragedy and loss by seeking to get back on my feet and heal,” he wrote in a Dec. 28 Facebook post. His GoFundMe campaign raised more than $2,000 for his “recovery.”

Despite prosecutors’ description of Harris as the building’s “creative director,” he previously told The Times he was merely an “artist and resident” at the Ghost Ship.

Convicting the men on manslaughter charges will be no simple task, legal experts said. Jean M. Daly, a former prosecutor in Los Angeles and San Francisco who led arson units in both cities, said prosecutors will need to prove Almena and Harris knew the deadly fire was a possibility.

The fact that prosecutors cannot prove how the fire began could also be problematic, Daly said.

“They have an undetermined origin and cause and that is a problem for prosecutors,” she said. “That is an awful tough case to make.”

Former Los Angeles Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley, however, said Almena and Harris’ behavior is likely to resonate with jurors.

“It is not so much the cause of fire that matters. Much more important is recklessness in having that building packed with stuff and occupied in violation of just about every safety code in the city and the state,” he said.

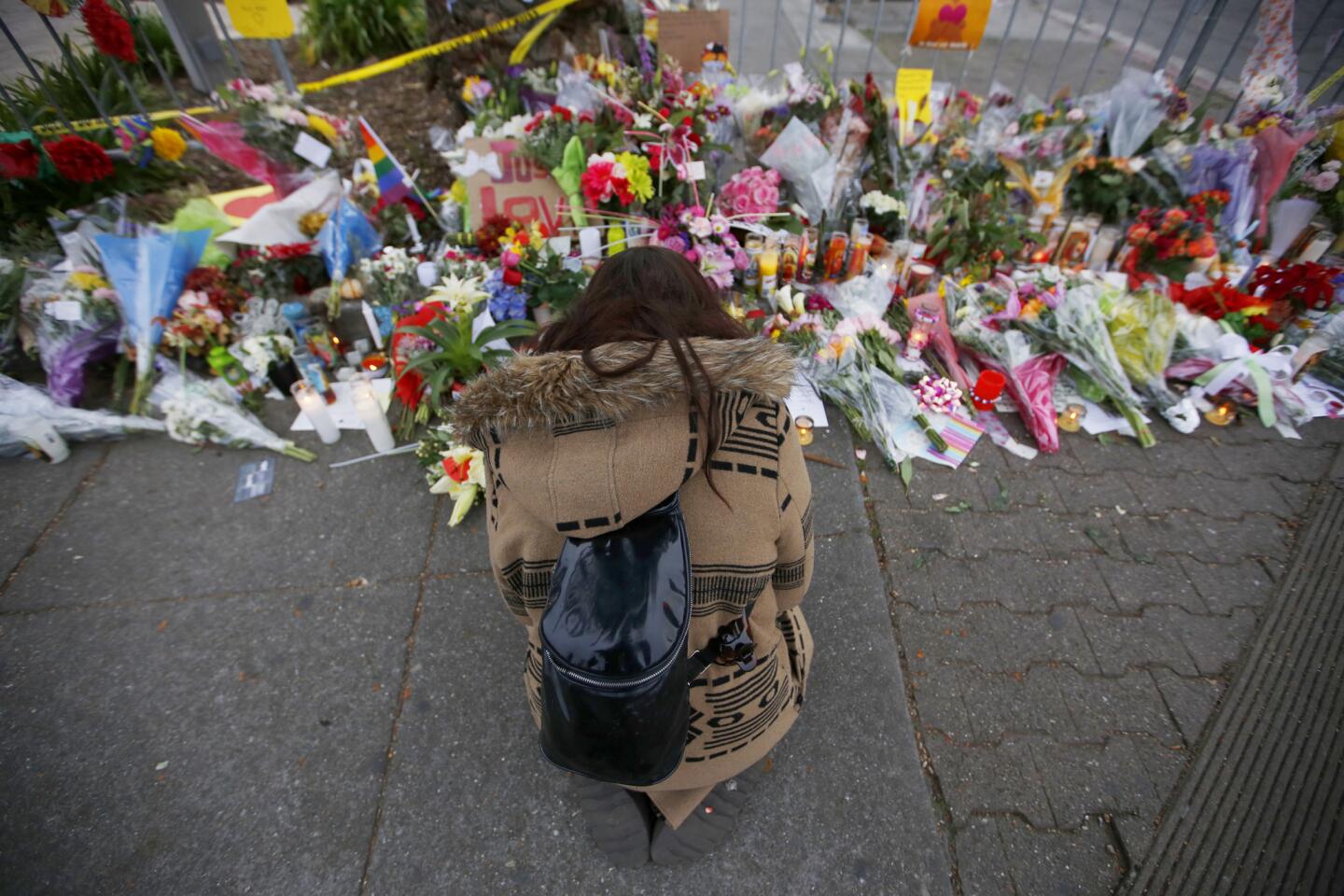

Outside the warehouse’s remains, hearts bearing the names of the 36 fire victims hang from a weeping willow tree of twisted iron branches and votives. Its base was still crowded with jars and vases filled with fresh flowers on Monday.

St. John reported from Oakland. Queally and Winton reported from Los Angeles.

Follow @JamesQueallyLAT, @LAcrimes, & @paigestjohn for more criminal justice news in California.

ALSO

Oakland officials well aware of problems at Ghost Ship before fire killed 36, records show

‘We’re all kind of searching.’ Mourners make pilgrimages to the Ghost Ship from Oakland and beyond

The L.A. DIY community contemplates a post-Ghost Ship life

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.