Furor over Oklahoma fraternity’s racist song may lead to lasting changes

- Share via

Reporting from Norman, Okla. — Years ago, a University of Oklahoma fraternity held a series of “Mekong Delta parties,” replete with camouflage, fake machine guns, sandbags and stretchers. Vietnam veterans objected.

Later, drunken fraternity members streaked across campus and urinated on a tepee and shouted racial epithets during Native American Week. A Native American student fasted for a week in protest.

In each instance, the fraternities said they would take steps to ensure nothing of the sort would happen again. They said they were sorry. University officials punished the perpetrators and urged the campus to move past the ugliness. For years, that was how things worked at OU.

Not this time.

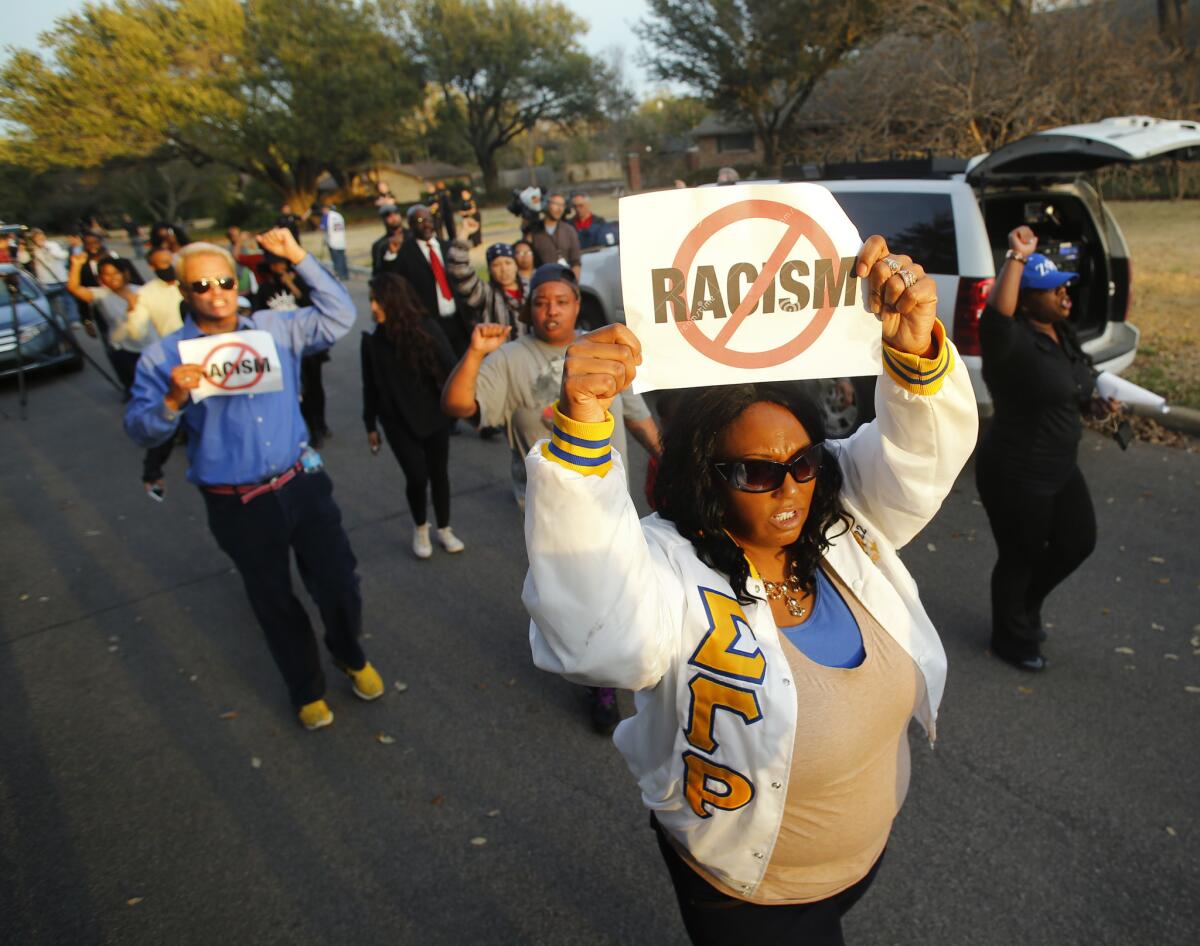

When members of Sigma Alpha Epsilon were filmed exuberantly singing a racist song with references to lynching, the disgust was campus-wide and the punishment decisive, fueled by the unavoidable evidence playing on TV, PCs and cellphones and by the timing — days after the 50th anniversary of the march from Selma and months after police shootings of unarmed black men that sparked protests and a national debate.

But the nine-second video of young men chanting the N-word has sparked more than anger.

The emotions and pent-up pain unleashed by the video have been so raw, so powerful, that they stand to reshape university culture for years to come.

Across campus, students and staff have been engaging in blunt, honest and sometimes painful discussions about race, ethnicity and identity — both in general and at the University of Oklahoma in particular. They’ve shared their dismay and disillusionment. They’ve shed tears.

Betty Harris, a professor of anthropology, remembers the earlier incidents, and the reaction.

“This is very different,” said Harris, who has taught for 30 years at OU. “There was a habit, or a tendency, to just move past those [other incidents]. But I see something different this time.”

Harris was encouraged by what happened at a meeting at the university’s business school Wednesday night. Scheduled long before the video became public, it was intended to address diversity.

The meeting transformed into a public conversation about the treatment of minorities on the Norman campus, 20 miles south of the capital. Most of the 200 or so in attendance were people of color, both students and faculty. Many were the first in their families to attend college.

Cheyenne Smith, a public relations major, said a man called her the N-word to her face on Wednesday morning. Tracey Medina, a 23-year-old Mexican American senior who’s two months from graduating, tearfully described getting a call from her parents in Tulsa, Okla., after the video aired.

“What’s happening? Come home,” her parents told her. “They hate you there.”

There were 27,278 students on the campus in Norman at the beginning of the school year, and 60% of them were white. The rest are a combination of international students and blacks, Asians, Latinos and Native Americans — along with students of two or more races.

They talked about what it felt like to be told they “talked white,” to never have a professor of color, to see Native American art displayed in a way that reinforces stereotypes of Indians as noble savages incapable of living in a modern world.

Micah Wormley, who was born a man but identifies as female, said she had no place on campus to feel comfortable.

“That is the kind of thinking that spread on that bus,” she said. “That is the face I saw on that bus.” In the grainy video first posted online March 8, two smiling white men dressed in tuxedos lead the song, including the N-word: “You can hang him from a tree, but he’ll never sign with me, there will never be a ... SAE.”

The university swiftly closed the Sigma Alpha Epsilon chapter and expelled two of its members, actions that stand in stark contrast to the handling of such incidents years ago, even under the same university president, David Boren.

Stephanie Eyocko, 20, of Dallas, who is black, rushed several sororities her freshman year as a condition of a $2,000 scholarship she received from a Panhellenic council. She enjoyed the parties at first, but soon soured on Greek life.

“The kind of parties they have here aren’t really sensitive: Cowboys and Indians, Fiesta, Border Patrol,” she said. “They had a white-trash party that wasn’t even sensitive to themselves.”

When she saw women in the background of the SAE video, some singing along, she immediately thought of sorority sisters she met while rushing and later partied with.

“I want the girls on the bus to speak up…. I want the girls to come forward” about what happened, she said.

“I’ve been on buses like that,” Eyocko said, noting they are often used to take couples to fraternity date parties.

She went to one at the invitation of a black fraternity member, and found herself the only other black person on the bus, constantly being asked to dance or “twerk.” She told her date afterward she didn’t want to go anymore because of “the constant assumptions.”

“Let’s not put it off on Greek-ness,” she said of the chant. “The Greek stuff needs to change and the culture needs to change, but individuals need to realize and question when they’re doing something that isn’t safe for black people.”

One University of Oklahoma assistant professor who spoke out about the video has endured harassment.

Mirelsie Velazquez, a Latina in the College of Education, spoke Tuesday about the pressures minorities often face on campus. By Wednesday night, she said, she had received threats specific enough to force her into hiding, along with her daughter, a freshman at the school.

To be sure, Oklahoma isn’t alone. There are troves of pictures, video and stories online about college-age students around the country committing acts of racial and ethnic insensitivity, usually as part of a party. In 2010, an off-campus party hosted by students from UC San Diego sparked racial tension there. The event, described as a “Compton Cookout,” mocked Black History Month and led to large student protests.

“South of the Border” or “Border Patrol” parties in various states have encouraged partyers to dress up as stereotypes, such as cholos or sombrero-wearing peons.

OU sophomore Grayson Richey transferred to the school from the University of Texas and noted that the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity at the Austin campus, known as Fiji, last month threw a Border Patrol party without being sanctioned by the administration.

“At Fiji they publicized it — they told people to come, they advertised it,” said Richey, 20, a sophomore from Austin whose mother is Mexican. “SAE is not going to say, ‘We’re having a lynching party, bring your hoods.’ Yet Fiji can say, ‘We’re having a Border Patrol party, bring your handcuffs.’”

At Oklahoma, it was two SAE pledges and an active member who in 1996 stole a tepee from in front of a library and tried to move it to the front lawn of a sorority. The fraternity president later expressed dismay.

“We welcome brothers of all races, creeds and colors into our bonds,” then-president Jeff Nash said in a statement to the Oklahoman newspaper, “so it is particularly unfortunate that these three men committed such a racially offensive act.”

That was two years after six Phi Kappa Psi members were disciplined for urinating on a tepee — the frat brothers denied it — while Native American students slept inside.

In January, a rumored “Cowboys and Indians” themed party caused a minor uproar, though the accused fraternity denied planning it.

All of these events may be considered now as pre-SAE — before the video, the uproar, and the demands to change.

Melissa Rosas, a junior, said the SAE incident could be “a blessing in disguise.”

Addressing a sea of Latino, Native American and black faces at the diversity forum, Rosas said it took the events of the last week to force students at the University of Oklahoma to take a close look at themselves. There were some white faces at the forum, too, and Rosas said she had reason for hope.

“I’ve never been prouder,” Rosas said, “than I am tonight.”

nigel.duara@latimes.com

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.