Lawyer Uses Skills to Zero In on Gun Lobby

- Share via

It’s hard to imagine Sayre Weaver as the California gun lobby’s Public Enemy No. 1. Slight and soft-spoken, the Yale-educated attorney doesn’t march or testify or legislate.

She litigates. Relentlessly. With a laser-sharp focus that has delivered a series of body blows to an industry long accustomed to beating back efforts at gun control.

For 10 years, Weaver has been working to staunch the flow of “Saturday night specials” -- cheap handguns that cost less than a good pair of sneakers and are the weapon of choice in the criminal milieu.

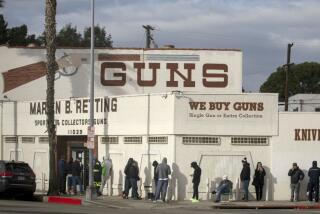

In 1996, she helped West Hollywood officials draft and defend California’s first local ordinance aimed at curtailing handgun sales. That success, despite a well-funded challenge by the gun industry, emboldened dozens more cities to tighten limits on weapons sales, making California a national leader in restricting handgun access.

“These are guns that have no legitimate sporting purpose,” says Weaver, who lives in La Habra Heights and practices in Brea. “The gun lobby had bamboozled everybody” into believing that restrictions violated constitutional protections.

“But there are all sorts of ways to regulate firearms dealers, in the same sort of way you regulate liquor stores: You have to operate out of a business district, you have to have a local license, you have to provide security measures, you can’t have minors in your store without an adult....

“It’s not an issue of putting them out of business but raising their level of responsibility. My task was convincing local governments that there are aspects of their operation that are well-suited to regulation.”

For her efforts, Weaver, legal director of the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence, was among three activists honored in San Francisco last month by the California Wellness Foundation with its 2005 Peace Prize for violence prevention.

“Some communities had more gun dealers than McDonald’s” when Weaver’s campaign began, said foundation consultant Laurie Kappe. “When she prevailed in West Hollywood, that opened up a willingness among others to take on the [National Rifle Assn.] and the gun industry. Sayre did such terrific legal arguments, it showed others this was a fight worth fighting.”

Weaver seems an unlikely leader on such an emotional issue.

“Most gun control advocates come from a place of passion that’s right on the surface,” Kappe said. “Sayre’s thoughtful, precise, very measured in the way she talks. She brings a surgeon-like precision to something that often gets clouded by emotion.”

Unlike many gun control activists, there is no personal tragedy propelling Weaver. She grew up around guns. Her father was a sportsman who taught Weaver and her brothers and sisters to shoot. “There were always rifles around the house,” she said.

But her parents also taught her to take nothing at face value, to question assumptions and trust her instincts when something feels wrong. And she felt something was dreadfully wrong early in her legal career in the late 1980s when she worked in Compton as a deputy district attorney.

Almost every case she prosecuted involved guns in some way -- drug trafficking, domestic violence, parole violations. “That made me aware of how gun violence can decimate a whole community,” she said.

In 1990 she went to work as a specialist in constitutional litigation for Richards, Watson and Gershon, a Los Angeles law firm that represents cities and public agencies. There, she was enlisted by West Hollywood officials to defend the city’s gun sales restriction. Her research led her to realize “how little I knew about gun regulation in this country; how little most people knew,” she said. “I thought this was an area where I could make a difference.”

Since then, she has become one of California’s foremost legal authorities on firearms legislation, winning two landmark cases -- in West Hollywood and Alameda County -- that established the right of local governments to restrict handgun possession and access.

Her legal efforts dovetailed with other forces to combat the dominance of the gun industry lobby, which had long held the state Legislature in a stranglehold with its financial and political clout.

“There were community efforts, like the Million Mom March. And there was polling data, showing that the public was for gun control,” recalled Kappe. “The combination of community activism, legal strategies and public support made cities more willing to pass their own ordinances. And once there was critical mass of cities and counties, the Legislature saw it was politically feasible and took over.”

Kappe likens it to the no-smoking movement: “Community by community, you restrict access without banning it. And finally, the Legislature takes notice.”

Weaver calls it an example of “the trickle-up theory” -- a grass-roots campaign powered to success by a weary populace fed up with gun violence.

She has no patience for arguments by gun enthusiasts that sales restrictions threaten their rights.

“This is not a benign product. A gun is a tool and it ought to be subject to consumer safety regulations,” she said. “The great freedom associated with their manufacture and sale benefit a very few at the expense of a great many.”

Weaver’s work has brought “odd sorts of threats” her way. “But the people who react vehemently against me are those true believers who think any kind of gun regulation means you’re trying to take our freedom,” she said. “Those are crazy people I can’t do anything about.”

These days, Weaver spends most of her time holed up in a spartan office with her computer, law books and a wall map that traces the route -- from manufacture to murder -- of a 9-millimeter Glock, the weapon used by white supremacist Buford Furrow to spray a San Fernando Valley Jewish community center with bullets and shoot a letter carrier to death in 1999.

Weaver is suing the gun’s manufacturer and distributors on behalf of the mother of the mailman and the families of three children wounded in the rampage.

Furrow, an ex-convict on parole at the time of the shooting, is now serving five life terms in prison. The gun he used was marketed by Glock as a “pocket rocket,” easily concealable and aimed at the illicit market, the suit alleges.

Weaver’s job has been made more difficult by last month’s Congressional approval of a bill shielding gun manufacturers and dealers from lawsuits by crime victims. But Weaver plans to challenge the constitutionality of the measure and its application to her case.

“We’ll be fighting it on every front,” she said. “We’re not going away. We’re not giving up.”

Her ability to weather setbacks and willingness to work in the trenches inspires her admirers.

“She could be a six-figure-plus attorney someplace, with her background,” Kappe said. “Her devotion to this cause has turned the tide for us. It really helps to have a lawyer who’s willing to stand up to the gun lobby.”

But Weaver says “making six figures was never anything of great interest to me.” She lives simply but comfortably with her husband, William P. Phelps, a professor of constitutional law at Whittier Law School. Her free time is spent caring for their two dogs and supporting animal rescue groups.

The joy of being a lawyer, she said, is “the great opportunity you have to follow your ideals, to apply your knowledge to something you care about and help make the world a better place.”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

At a glance

* Sayre Weaver was named after her father, Howard Sayre Weaver, a 1948 graduate of Yale who was initiated into the Skull and Bones society alongside George Herbert Walker Bush, former president and father of the current commander in chief.

* Weaver was born in Bangkok, Thailand, where her father served with the U.S. Foreign Service. She spent her early childhood in Munich, Germany. The family returned to the United States and settled in Connecticut when she was in the second grade.

* She graduated from Yale in 1975 and earned her law degree from the university in 1984. She was part of the university’s first women’s crew team in 1972.

* Her two dogs are both mixed-breed “part-Chow mutts” she rescued from the streets.

* Weaver will donate the $25,000 award that comes with her California Wellness Foundation Peace Prize to two nonprofit groups: $20,000 to the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence (of which she is legal director) and $5,000 to Girls Leap, a mentoring group founded by her sister, a Wellesley College professor, to train college students to help at-risk teenage girls avoid violence and abuse.

* She and her husband have a “hideaway cabin in the Midwest.” It’s their favorite vacation spot because “we only like to go where we can take our dogs.”

Source: Times staff reports

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.