Russian-Born Soldier of Fortune Thrived in West

- Share via

Some of his critics called him a man without a nation in search of a good fight.

Emilio Kosterlitzky was the classic soldier of fortune, a Russian imperial sailor who jumped ship to enlist in Mexico’s army. He wound up working for the FBI in Prohibition-era Los Angeles, hunting down bootleggers and rumrunners.

Born in a czarist Russian Army camp, he lies buried in an East Los Angeles cemetery.

Kosterlitzky -- whose policy was to shoot first and ask questions later -- was a legendary warrior who spent half a century in the uniforms of Russia and Mexico and the plainclothes attire of a U.S. liquor-buster.

While in Mexico’s service, he captured the Apache chief Geronimo, but released him because he felt Geronimo was an honorable adversary. He chased Pancho Villa until his own horse gave out and he ran out of bullets.

But it was his fearlessness and ruthlessness in dealing with bandits and political opponents during the Mexican Revolution, his linguistic skill and his freewheeling style -- fighting on both sides of the border -- that earned him a welcome in California.

Kosterlitzky’s colorful story is documented by myriad Los Angeles Times articles published during his lifetime and by the book, “Emilio Kosterlitzky: Eagle of Sonora,” by Cornelius C. Smith Jr., published in 1970.

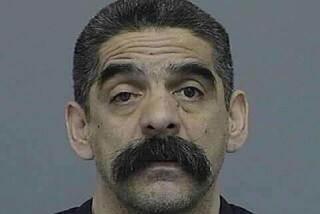

He was born in Moscow in 1853, the child of a Russian father and German mother. His father was a fearsome Cossack -- an archetype of a large, mustachioed man in a lambskin hat astride a raging stallion, cutting down enemies of the motherland with a flashing sword.

The younger Kosterlitzky also dreamed of horses and the wild frontier, but somehow ended up in the navy. He hated the sea, loved horses and longed for frontier adventures like his father’s. In 1872, he jumped ship in Venezuela, swam ashore and headed north, where he enlisted in the Mexican army.

By the Apache wars of the late 19th century, he was a captain. The wars freed troops on both sides of the border to pursue outlaws or anyone else who opposed them.

Kosterlitzky, who could speak, read and write eight languages, became something of a rough-and-tumble cowboy and cross-cultural broker.

At the turn of the 20th century, U.S. investment in Northern Mexico was booming, and American businessmen counted on Mexican authorities to help protect their interests.

Kosterlitzky was a top-ranking officer of Mexico’s border patrol, known as the rurales, whose members were often hardened criminals and bandits. They policed the border along with the Arizona Rangers to combat smuggling and suppress labor strikes. Kosterlitzky, who was both feared and respected, always slept with a revolver in each hand.

In exchange for doing the dirty work of politicians and the corporate elite, Kosterlitzky was given a free hand to practice his own style of law enforcement -- which could be bloody.

In 1906, Mexico sent him and 75 rurales to quell a strike at the Cananea copper mine near the Arizona border. But 300 Arizona Rangers arrived first, facing several thousand miners who demanded better pay and working conditions. Several bloody clashes resulted in the deaths of about six Americans and 35 Mexicans, but tensions calmed.

Within hours, however, Kosterlitzky and his men rode into town and put Cananea under martial law. They rounded up nearly a dozen ringleaders and shot or hanged them from the same tree.

Kosterlitzky was widely praised as a hero, but his actions have since been criticized in some parts as a massacre.

Some of the survivors became leaders of the Mexican Revolution, which broke out in 1910.

Kosterlitzky moved his wife and children to Bisbee, Ariz., to keep them safe, then set about recruiting a federal army. He showed up at a Mexican prison and “drafted” 25 inmates by handcuffing them and sending them off to boot camp. He scribbled a note and pinned it to the first man: “Here are 25 patriotic men; please return my handcuffs and I’ll send you another 25,” according to Smith.

On March 13, 1913, the U.S. 5th Cavalry was about a football field away, in Nogales, Ariz., watching Kosterlitzky and his 280 rurales defend the Mexican state of Sonora against 4,000 rebels led by Gen. Alvaro Obregon, a future president of Mexico.

Bullets began to fly, wounding at least three people, including a U.S. soldier and a small boy. An American officer ordered his company bugler to sound the Mexican retreat. Shooting by the revolutionaries and the rurales stopped. None too soon: Kosterlitzky and his men had run out of ammunition.

With the rebels on the verge of victory, Kosterlitzky and his rurales sought American sanctuary. His troops were put in a Nogales prison camp -- according to international law, the neutral U.S. had to hold them as prisoners of war until they could be repatriated. Kosterlitzky, by now a colonel, was given parole and lived nearby with his family. He visited his men every day.

On Aug. 12, 1913, Kosterlitzky and a train-load of Mexican prisoners rolled into San Diego. They were transported to Ft. Rosecrans, now a housing development and national cemetery, where they lived in tents for nearly a year.

Kosterlitzky was still on parole, living with his family near the fort, but responsible for his countrymen’s conduct. But Mexico refused to pay for their upkeep. Southern California newspapers’ headlines read: “Paid Vacations Courtesy of Uncle Sam.”

Homesick and tired of bad press, 65 prisoners escaped. Kosterlitzky took it as a personal affront. He mounted up with American troops to hunt them down and persuaded most to return to Ft. Rosecrans. Others turned themselves in.

On Oct. 2, 1914, the prisoners were repatriated after Mexican immigration agents assured Kosterlitzky that “no further threats hung over the heads of his men,” Smith wrote. Kosterlitzky decided to stay in the United States, because he had been on the wrong side of the revolution. But he never gave up his Mexican citizenship.

During Kosterlitzky’s last days at Ft. Rosecrans, an FBI agent offered him a job in Los Angeles: To mingle with Mexicans and flush out any revolutionary activities against the U.S. He moved with his family to L.A., where he continued working for the FBI, as an undercover agent and a translator.

By now, Kosterlitzky was well into his 60s. His clandestine service included wearing sunglasses and casual clothes and sunning himself on benches at Pershing Square, where he engaged strangers in talk about the war in Europe. He “occasionally turned up a dyed-in-the-wool German sympathizer,” Smith wrote.

Even before the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, Los Angeles was a hotbed for German agents working to enlist Mexican aid in the war against the United States.

As the war unfolded, the nation’s anti-German sentiment prompted many Germans to change their names to find and keep work. Kosterlitzky distributed “Beware of Spy” cards, asking citizens to watch their neighbors and report suspicious activities. Angelenos reported smuggling, tunnel-digging and even a supposed Morse code message on a clothesline using socks and underwear. Kosterlitzky followed up on all leads, most of which came to naught.

In 1922, Kosterlitzky was assigned to a so-called Prohibition team that hunted down bootleggers, rumrunners and gunrunners. His last official act for the U.S. government was investigating gunrunning from the Imperial Valley into Mexico, in a supposed plot to take over Baja California. On Aug. 15, 1926, Kosterlitzky and three other federal agents arrested eight Mexicans and one American. He retired the next month.

Kosterlitzky, who had married three times and fathered 10 children, died in 1928, at 74. On his deathbed, he supposedly told the offspring who had come:

” ... I can leave you nothing except the most wonderful fortune in the world: your mother, a jewel beyond price, and a name you can be proud to bear.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.