Vicious cycle of frequent fires is remaking Southern California’s ecology

- Share via

Jon Keeley is standing on a dirt road in western Riverside County, looking out across the Box Springs Mountains. Instead of a thick coat of native shrubs, the slopes are covered with a shriveled tangle of mustard, wild oats and red brome.

Too much fire is the culprit.

Since 1957, there have been 33 fires larger than 100 acres in the Box Springs -- more than the area’s native coastal sage and chaparral could withstand.

“Scenes like this you can see all over Southern California,” says Keeley, a research scientist for the U.S. Geological Survey.

Chaparral is accustomed to intense, periodic wildfire. But as Southern California’s population has increased, so has the frequency of wildfires, most of which are caused by people. Shrub lands that used to burn every 50 to 150 years on the coast and every 30 to 100 years inland are burning far more frequently in some areas.

The chaparral and coastal sage don’t have time to regrow before the next inferno. Hillsides turn into ugly outposts of invasive weeds.

The transformation is impoverishing the biological community. Some species, such as coyotes, will do fine. Those that need a more complex habitat, such as bobcats and the coast horned lizard, won’t.

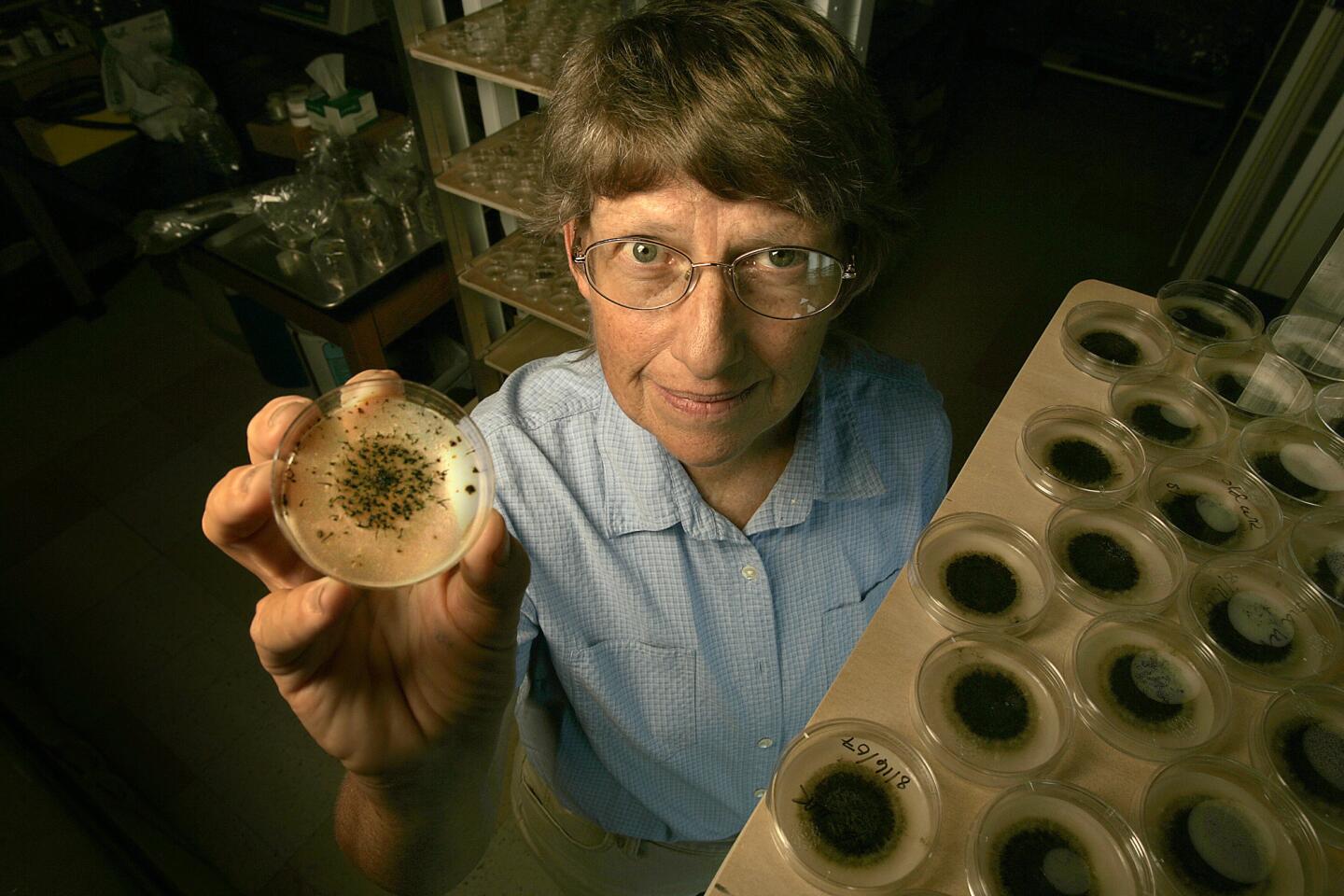

“We can go to places that are invasive grasslands now that are missing a lot of species,” said Robert Fisher, a USGS research biologist in San Diego.

The change in vegetation extends the fire season because many invasive plants burn virtually year-round. Toss a cigarette into a stand of coastal sage in June and in most years it won’t ignite. Do the same to a bed of red brome and it will.

And grasses don’t hold the soil or water as well as deep-rooted shrubs, leaving hillsides more prone to landslides and erosion.

In time, Keeley said, most of Southern California’s wildlands could look like the Box Springs Mountains, largely bereft of their signature stands of chamise, manzanita and California buckwheat.

“We could lose it all.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.