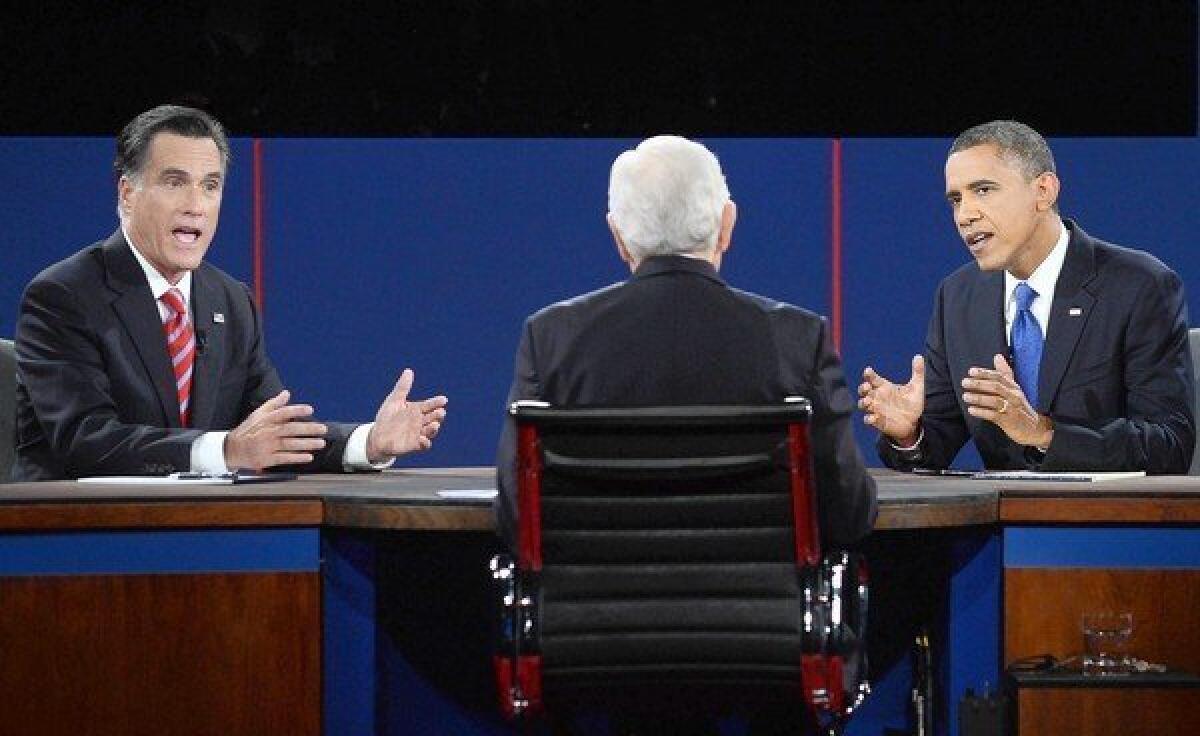

Obama reverses roles, comes out swinging at Romney in final debate

- Share via

BOCA RATON, Fla. — President Obama and Republican nominee Mitt Romney made their closing appeals to voters in a final debate that featured an unusual reversal of strategy — Obama adopted the typical challenger’s stance of underscoring differences, while Romney repeatedly sought to mute them.

From the start of the debate, Romney made clear that a chief goal was to answer a question he had left hanging a week ago at the second encounter between the two men: how he differed from George W. Bush. He repeatedly said he opposed war, and although he called for higher military spending, he downplayed military solutions to foreign problems.

In his answer to the debate’s first question, Romney congratulated Obama for “taking out Osama bin Laden and going after the leadership of Al Qaeda.”

PHOTOS: Memorable presidential debate moments

But, he quickly added, “we can’t kill our way out of this mess.”

He maintained that approach throughout, mentioning the word “peace” or a variant 12 times during the 90-minute debate, including twice in his closing statement, according to the debate transcript.

Obama did not mention the word once, the transcript showed, preferring, instead, variations of the word “safe.”

As with Romney, Obama made his emphasis clear from his opening words: “My first job as commander in chief,” he said, “is to keep the American people safe. And that’s what we’ve done over the last four years.”

Obama accused Romney of trying to “airbrush history” by changing his positions. He sharply, at times sarcastically, criticized Romney’s stands, accusing him of sending “mixed signals” to allies and of displaying “wrong and reckless leadership that is all over the map.”

Responding to Romney’s charge that the U.S. Navy has fewer ships than at any time since World War I, Obama shot back, “Well, governor, we also have fewer horses and bayonets because the nature of our military’s changed. We have these things called aircraft carriers where planes land on them. We have these ships that go underwater, nuclear submarines.”

The result was to some extent a mirror of the first debate between the two men in Denver. That time, Obama tried to avoid contentious, partisan exchanges and ended up looking listless. Voters by wide margins said Romney won that first debate. This time, instant polls indicated that voters thought Obama had done better.

Whether this final debate will have anything like the impact of the first one remains to be seen. The first encounter revived Romney’s campaign after several weeks of apparent drift and set the race onto its current course, in which polls indicate the contest is too close to call nationally and in several of the most hotly contested states.

In an excruciatingly tight race, both campaigns believe that women make up the majority of the voters who are wavering on their choices, and the candidates’ differing word choices and overall approaches reflected their strategies on how to appeal to them. Both frequently mentioned their support for gender equality in the Middle East. But much of the night revolved around their different approaches to that trade-off of peace versus safety.

For much of the last year, Romney has often advocated policies that were more hawkish than Obama’s. Democratic strategists have tried to tie him to Bush’s policies, particularly his military intervention in the Middle East, which remains highly unpopular with many voters, particularly women. Obama at one point during the debate explicitly mentioned Romney’s past praise for Bush and former Vice President Dick Cheney.

INTERACTIVE: Battleground states map

Romney and his advisers clearly sought to avoid that trap, much as during the first debate he had cast his domestic policies in more moderate terms.

“A recurring theme from Romney tonight was ‘I’m not going to commit American troops,’” said Sen. Richard J. Durbin (D-Ill). “You know why? Because during the entire Republican primary [there was] so much saber-rattling. That isn’t what the American people are looking for.”

Indeed, through much of the debate, Romney seemed to avoid controversy in general. He portrayed his positions as being mostly in concert with Obama’s on Syria, Afghanistan, Iran’s nuclear program and the U.S. intervention that toppled Moammar Kadafi’s regime in Libya, although he suggested that he could execute those policies more effectively. When Obama went after him, Romney seldom shot back in kind, saying twice that “attacking me is not an agenda.”

He did not use any of the attack lines that his campaign surrogates had used on foreign policy issues in recent weeks. For example, he did not push Obama on the deaths of U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans in an attack in Libya. Nor did he challenge the idea of bilateral talks between the U.S. and Iran over the nuclear issue, which his campaign aides had criticized.

Instead, it was Obama who was on the attack for much of the debate. At one point, he noted that Romney had said during the 2008 campaign that the U.S. should not “move heaven and earth” to catch Bin Laden, and then went on to talk about a girl named Peyton he had met on a recent trip to the World Trade Center site in New York who had lost her father on Sept. 11, 2001.

The girl told him that Bin Laden’s death had brought her closure, Obama said.

“When we bring those who have harmed us to justice, that sends a message to the world, and it tells Peyton that we did not forget her father,” Obama said. “I make that point because that’s the kind of clarity of leadership” the country needs, he said. “What the American people understand is, is that I look at what we need to get done to keep the American people safe and to move our interests forward, and I make those decisions.”

Most Americans pay little sustained attention to foreign policy. But the president’s role as commander in chief does loom large in voters’ minds. Obama clearly went into the debate believing that playing up that role would be his strong suit.

Foreign policy forms an area of relative strength for Obama. Most polls have shown him holding an advantage over Romney on foreign affairs. A Washington Post/ABC News poll released shortly before the debate showed the two tied on the subject. In either case, the lack of an advantage for the Republican reverses a pattern that has held for several decades in which the GOP usually has held the upper hand on defense and security issues.

Voters have credited Obama with ending an unpopular war in Iraq and winding down a second unpopular conflict in Afghanistan and with the death of Bin Laden.

At the same time, both men tried often to shift back to the domestic economy, frequently repeating their now-familiar stump speeches.

One of their most heated clashes was on a topic that has been one of Obama’s strongest points in the campaign — Romney’s opposition to the bailout of the automobile industry in 2009. The Obama campaign has emphasized that issue constantly in key Midwestern battlegrounds, particularly Ohio.

Romney insisted that Obama had misrepresented his position.

“I’m a son of Detroit. I was born in Detroit. My dad was head of a car company,” Romney said. “I like American cars. And I would do nothing to hurt the U.S. auto industry.

“My plan to get the industry on its feet when it was in real trouble was not to start writing checks. It was President Bush that wrote the first checks. I disagree with that. I said they need — these companies need to go through a managed bankruptcy, and in that process they can get government help and government guarantees.”

Obama interrupted repeatedly to say that Romney had not promised government help during the bankruptcy process. In past interviews and other public statements, Romney has said, “My own view is that the auto companies needed to go through bankruptcy before government help.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.