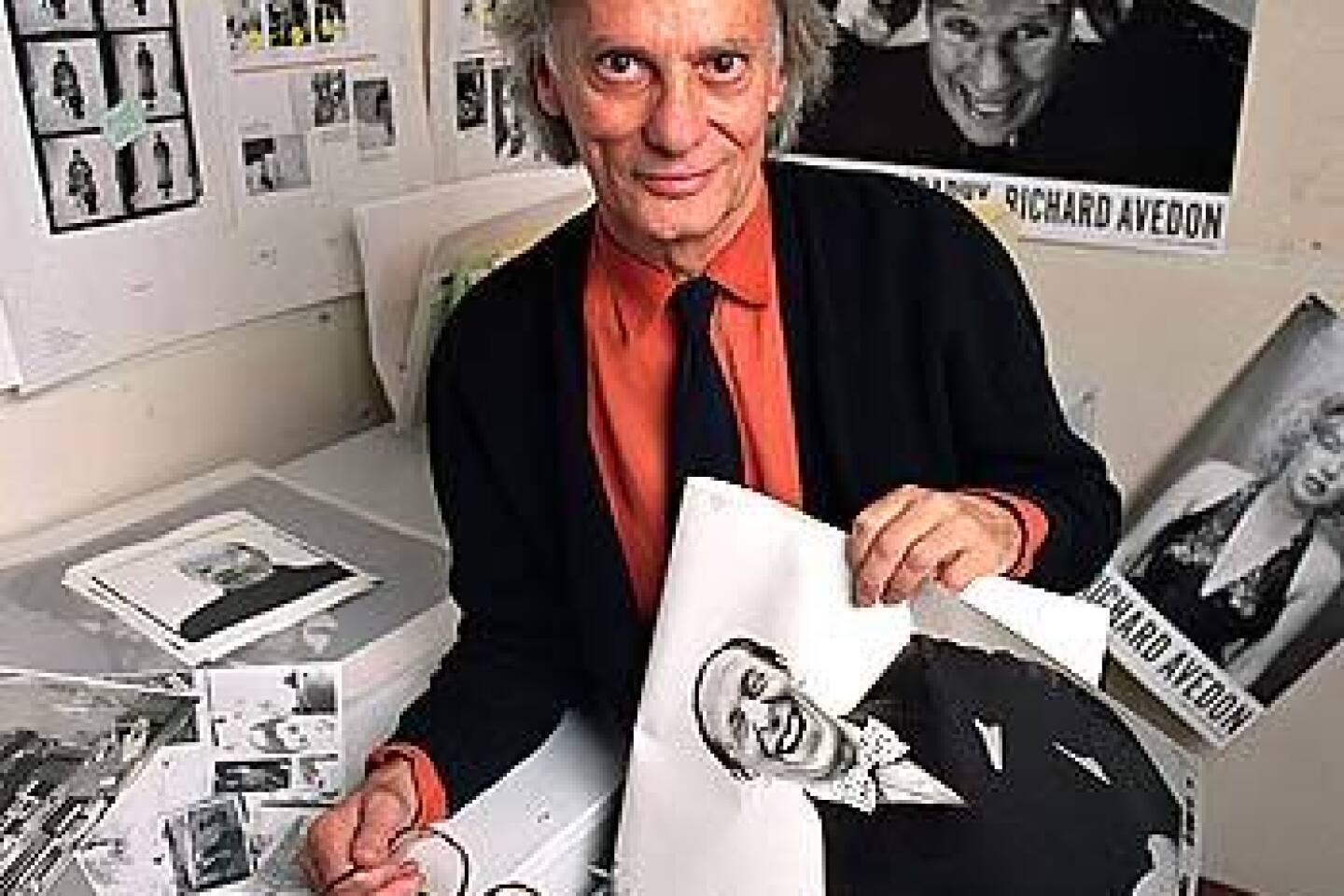

Photographer Richard Avedon Dies

- Share via

Richard Avedon, who during a career spanning more than 50 years was renowned both for his stripped-down black-and-white portrait photography and his playful yet sophisticated fashion shots, died today.

Avedon, who was 81, died at Methodist Hospital in San Antonio, Texas, of a blood clot in the brain, according to his son, John.

Avedon had been on assignment in Texas for New Yorker magazine, completing a project called “Democracy,” a portfolio about politics in America. David Remnick, editor of the magazine, said he plans to publish the work before the Nov. 2 presidential election.

As a fashion photographer, Avedon was among the first to replace the statuesque poses of the past with vivacious action scenes that commanded the pages of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue magazines from the mid-’40s through the 1980s. His models nuzzled elephants in Egypt, hugged sweaty cyclists on the Champs-Elysee in Paris and leaped like gymnasts through his New York City studio.

But increasingly he preferred making portraits of public figures, capturing their inner worlds rather than romanticizing their lifestyles. By eschewing soft lights and cluttered props, he took a stark, often harsh look at his subjects. Many of the photographs taken later in his life were done for the New Yorker, which ran his portraits of people in the arts and politics as a weekly feature starting in 1992.

“Avedon gave us the pared-down study of the famous person, a stripped-away look at their humanity,” said Arthur Ollman, director of the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego, in an interview earlier this year with The Times. “It is portraiture as interrogation.”

Actors, presidents, writers and social activists stood against a blank white background “as if he had pinned them to a wall like a specimen,” Ollman said of Avedon’s style.

The results could be cold and critical. And yet, said Ollman, “being photographed by Avedon meant you’d made it.”

Marilyn Monroe, dressed in sequins and diamonds, appeared to be a bit frightened before Avedon’s camera. President Ford squinted warily in a 1976 portrait that suggested an honest if uninspired CEO. Playwright Samuel Beckett, facial lines as deep as tractor tracks, gazed into the camera, seemingly at peace with his demons.

Avedon’s eye-to-eye stance regarding his subjects was sometimes compared to German photographer August Sander, who, as the Nazis were rising to power, documented farmers, preachers and others as if they were endangered species.

Avedon once described what he saw in many of the famous faces he photographed.

“People — running from unhappiness, hiding in power — are locked within their reputations, ambitions, beliefs,” he wrote in “An Autobiography, Richard Avedon” about his portraits of such tenacious survivors as Kennedy family matriarch Rose Kennedy, writer Truman Capote and pianist/raconteur Oscar Levant.

Other images in the book — of war victims and mental patients — spoke to a different kind of portrait.

“People, unprotected by their roles, become isolated in beauty and intellect and illness and confusion,” he wrote.

Avedon found his means of artistic expression early and was among the first to adapt it to larger-than-life-sized portraits — 4 by 6 feet images in the late 1950s, 10 by 30 feet or more in the ‘60s.

“In art, the monumental size generally had been reserved for gods and presidents,” Robert Sobieszek, curator of photography at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, said today. “Avedon applied it to everyone, from Andy Warhol to ordinary workers in the American West. What he pulled off was the democratization of the photographic image.”

Avedon was attracted to stylish rebels. College student Julian Bond and other civil rights activists stood in formation like an army before Avedon’s camera; Warhol and his entourage ambled across a three-panel mural; the bearded, bell-bottomed “Chicago Seven” antiwar activists — including Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin and Tom Hayden — bore looks of surprise.

“Avedon’s photographs are unrivaled as documents of our time,” said Mia Fineman, research associate of the photography department of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. “He created an encyclopedia of the key players in the counterculture, the intellectual culture, politics and the arts.”

Throughout most of his career, his fascination with street photography and news shots edged its way into his fashion work. For a 1962 layout that ran in Harper’s Bazaar, he set up a tabloid news series using Mike Nichols, then a comic and now a film director, and supermodel Suzy Parker as subjects. The glamour couple dashed from a Paris fashion show to a black-tie gala and finally to the American Hospital of Paris. A second look at Parker’s wrists revealed they were bandaged, to suggest a suicide attempt.

Avedon didn’t invent the tabloid-fashion shoot or hold the monopoly. Helmut Newton’s fashion “stories” were blatantly erotic; Guy Bourdin created surreal scenes. And, as lesser talents tried their hand at it, the “stories” frequently upstaged the designer goods in the picture. Avedon managed to keep a balance.

“With Dick Avedon you always knew you were looking at a fashion photograph,” said Grace Mirabella, who was editor of Vogue at the time the photographer landed a record $1-million annual contract there in 1966. “He never tried to forsake style for a strong image.”

He did, however, fight for control of his work, battling with several generations of fashion magazine editors. A colleague once asked him how he dealt with the struggle. He answered by making a fist with one hand and smashing it into his palm.

By the early 1980s, Avedon told friends he had lost interest in fashion. It was a paycheck, and the food was good at fashion parties. Beyond that, he said, “the whole thing is silly.” He left Vogue in 1990 and went out on his own as a freelancer.

Born in New York City on May 15, 1923, Avedon was the only son of Jacob Isaac Avedon, a Russian Jewish immigrant who owned a women’s clothing store on Fifth Avenue but lost it in the 1929 stock market crash. His mother, Anna, taught him about style and the arts. The image-conscious Avedons borrowed handsome dogs to pose with them in family photographs.

But home life was not the perfect world of the family pictures, Avedon later said. His father was critical and remote. His younger sister Louise was a schizophrenic who spent nearly 10 years in mental institutions before dying at age 42.

Avedon started planning his future when he was still a schoolboy, collecting autographs of actors, entertainers and musicians because “I wanted to be one of those people,” he said in a 1995 PBS special, “Richard Avedon, Darkness and Light,” which was part of the “American Masters” series. Their signatures amounted to his personal manifesto: “I want to get out of this apartment, this family, this world.”

He took photographs from the time he was a child. After high school, he joined the merchant marine, where for two years he took photos for identification cards — an experience, he said later, that was important to his future work.

From the merchant marine he entered the design program at the New School for Social Research in New York City. His teacher, Alexey Brodovitch, was also art director for Harper’s Bazaar, and Avedon became a staff photographer for the magazine in 1945. Brodovitch was his mentor, and Diana Vreeland, who eventually moved to Vogue, was the flamboyant fashion editor he came to think of as his “brilliant, crazy aunt.” Still, he said, his real interest was never the clothes.

“I liked girls who were full of imagination and fun. I loved watching them move,” he told People magazine in 1994. “I wasn’t interested in fashion but in making images that reflected a burst of energy and joy.”

He was inspired by photojournalist Martin Munkacsi, whose 1930s fashion shots featured such outdoor locations as the beach, where athletic-looking models dipped into the surf and strode along the shore. Another influence was Jacques-Henri Lartigue, whose turn-of-the-20th-century images showed women together at the cafe or in the park, always caught up in their own world.

Avedon married Dorcas “Doe” Nowell in 1944; they divorced five years later. He married Evelyn Franklin in 1951, with whom he had his son, John, before the couple separated.

“What happened is, I’m married to my work,” he told People magazine.

His son and four grandchildren survive him.

By the time Avedon left Harper’s Bazaar for Vogue, he was wealthy and famous — actor Fred Astaire had modeled himself after Avedon to play stylish photographer Dick Avery in the 1957 film “Funny Face,” with Audrey Hepburn as his muse.

Avedon was a staff photographer at Vogue when he had his first major museum exhibition, in 1974, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. It featured a series of realistic portraits of Avedon’s father, who was by then a frail old man losing his battle with cancer.

Asked why he made the series, Avedon said in the PBS documentary: “It gave me a sort of control over the situation. I got it out of my system and onto the page.”

Images of decay and death had attracted him from the time he was a young man. His early work included photographs of skeletons in the Roman catacombs and the dead at Pompeii, as well as the mentally ill.

“I photograph what I am afraid of,” Avedon said in the PBS documentary. “My work is meant to be disturbing in a positive way.”

The year he exhibited his portraits of his father, Avedon became dangerously ill with an inflamed heart. During his recovery he traveled the western U.S. working on “In the American West,” portraits of ranch hands, farmers, waitresses and others. The book was published in 1985 to accompany a traveling exhibition.

“He had a deep knowledge of human nature,” said Laura Wilson, his studio assistant of more than 20 years. Wilson made the trip West with Avedon, taking photographs of him for her book “Avedon at Work: In the American West.”

“He was moved by the emotional contradictions in his subjects,” Wilson told The Times this year.

In the 1980s, Avedon took several photographs that were shocking for their time. Perhaps the best known was one in 1980 of Brooke Shields at age 15 striking a suggestive pose wearing skin-tight jeans for the Calvin Klein ad, “Nothing Comes Between Me and My Calvins.”

A year later he photographed actress Natassja Kinski lying nude on the floor, a python slithering from her toes to her lips. The photograph appeared in Vogue and was made into a poster that sold 2 million copies.

“He could be very provocative,” said fashion historian Kennedy Fraser, a former fashion editor for the New Yorker and frequent contributor to Vogue. Recalling that European photographers were the first to work near-explicit sex and tabloid-like setups into their fashion work, she added, “I’m not sure he was a path-breaker, but he brought others’ ideas into the American mainstream.”

Avedon left Vogue in 1990 but stayed in the style orbit directing television commercials for designer perfumes — Calvin Klein’s “Obsession” and “Coco” by Chanel.

While few magazine editors or art directors who worked with him wanted to be quoted, many said he could be extremely difficult.

“His ego is so overblown. He is self-centered to a fault. He loves his own work to the exclusion of all others,” one of them told People magazine in 1994.

Avedon himself told stories about the many hours that Kinski spent lying on the floor in his studio, waiting for the python to slither along her flesh, just so. For another photograph, “Bee Man” (1994), Avedon persuaded professional beekeeper Ronald Fischer to stand still while he smeared queen-bee hormone on Fischer’s bare chest and face, then set loose hundreds of bees to alight on those places. Before Avedon got the picture he wanted, bee stings brought tears to Fischer’s eyes, but the man did not move.

The official career change to portrait photographer came in 1992, when Avedon was hired as staff photographer for the New Yorker — the first in the magazine’s 67-year history.

“We wanted the best,” said New Yorker magazine editor Remnick after hearing of Avedon’s death. “Avedon in his 70s and 80s had the energy of someone is his 20s. He was a Promethean energy force.”

Many of Avedon’s photographs for the magazine were of writers, stage directors, composers and others in the arts. A number of them were from the photographer’s personal library, yet they had the immediacy of his most recent work.

Seemingly inexhaustible through his 70s, Avedon lectured in the U.S., France and Germany, taught a master’s class at the International Center of Photography in New York City and was honored with prize after prize. The most prestigious included lifetime achievement awards from the Council of Fashion Designers of America in 1989 and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in 2000. In 2001, he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In a major exhibit of his portraits from the 1940s onward at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2002, Avedon included a recent self-portrait, a triptych. In one image, his hands are tucked away. In another, his fingers are knotted together. He is the artist, attending his own show, standing by his work.

He seems to be saying: Let others be the judge of it.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.