Superheroes Minus Masks

- Share via

In public, he’s just another nonthreatening chump. In private, he’s a flamboyant enemy of the unjust. For a century, the fictional figure we call the superhero has embodied our fantasies of power -- but also one of our deepest fears. Even the bravest superheroes have lived in terror of having their secret identities revealed. They have mirrored, in cartoon form, our own fears of having our private selves exposed to the world. But now that’s changing, as our beliefs change about what is public and what is private, what can and can’t be revealed.

The Scarlet Pimpernel, a fop who secretly rescued innocent nobles from the guillotine in revolutionary France, popularized the hero with a hidden identity. He was created in 1903 by Baroness Emmuska Orczy. As a Hungarian aristocrat paying her way by writing romances for bourgeois English audiences, she knew a few things about masks and hidden agendas.

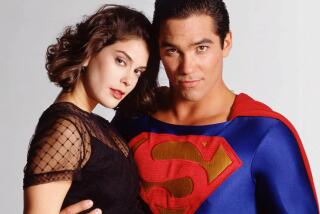

The Pimpernel spawned Zorro, the Shadow and the Lone Ranger. Then, in the 1930s, a Jewish mama’s boy from Cleveland named Jerry Siegel created a new kind of hero. Siegel’s father was killed by a robber when Jerry was in his teens, and soon Siegel conceived of a bulletproof crime fighter named Superman. He gave his hero a secret identity, but with a potent twist. The Pimpernel and his imitators were well-established adults who invented masked alter egos who could battle evil without jeopardizing their social positions. Superman came from another world, already superhuman, and learned to pass as an earthling. Superman was the reality, Clark Kent the invention.

Superman’s print debut in 1938 caused a sensation. The nebbish stripping in a phone booth to stand revealed as the “man of tomorrow” became a universal symbol for an absurd but compelling wish fulfillment -- Superman was a solace in a conformist society. Beneath the masks and uniforms we are issued for school and work, we harbor dreams, powers and dramas that make us unique, but we hide our differences, our private selves, to go along and get along.

Siegel never spoke of the murder of his father. He wanted the world to see him as a big-shot writer, not a wounded boy.

He never addressed his Jewishness either, even when others pointed out how Superman could be read as a metaphor for the Jewish immigrant experience: Rocketed from an ancient world now gone, his destiny and special powers are kept under wraps because the goyim wouldn’t understand him. (Jules Feiffer said every kid in his neighborhood knew Superman was Jewish: “Who else but a Jew would make up a name like Clark Kent?”)

Superman insisted that his work as a hero must end if the truth were exposed. Why? Why not just be superhuman in public? But readers didn’t waste time worrying about the illogic of Clark Kent -- they understood his role emotionally. Batman, Wonder Woman and the generation of superheroes that followed upheld that inviolable, protective duality of public and private selves.

Then, in 1961, things began to change. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, two more nerdy Jewish kids from rough backgrounds, created the Fantastic Four, who fought alien menaces under their own names. Six years later, Lee and Kirby’s Incredible Hulk was outed by his teenage sidekick. When the X-Men rose to popularity in the late 1970s, not only did they have no secret identities, they wrestled openly with the challenges of their mutant “otherness.” Their stories were not about keeping secrets but about creating family and identity with the help of other oddballs.

This year, Hollywood finally put its mass-market stamp on the shift, when it ripped off Peter Parker’s mask in “Spider-Man 2.” He looks up in horror at the crowd around him that has discovered his true identity. Then a kid says, “It’s OK. We won’t tell anybody.” His secret is safe, not because it’s really secret but because he can trust the world to handle it.

A friend of mine, David, took his sixth-grade son, Ike, to “Spider-Man 2” -- along with Ike’s “other dad,” as family friends so scrupulously say -- and the message made him a fan.

“When I was a teenager, superheroes were obviously about being queer,” David says. “Clark Kent shedding that hideous blue suit and shooting into the sky in his tights? What else? But overshadowing the joy was that fear that people would learn the truth -- until that moment in ‘Spider-Man 2.’ ”

The ease with which that fear was dismissed and the warmth with which the audience embraced the movie show that it was more than a clever twist on a formula. That kid voiced a fundamental change in our attitudes about the boundaries that separate our hidden and public selves.

“We’re still afraid to be exposed,” David says. “Our sexuality, backgrounds, absurd families, nerdy fantasies. But when the truth comes out, the world says it’s no big deal.”

We may wrap ourselves in the uniform of normality, but we can also let the bright colors of our costumes peek out from underneath. We can accept each other, as nebbishes and as heroes.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.