Restore the vote to felons

- Share via

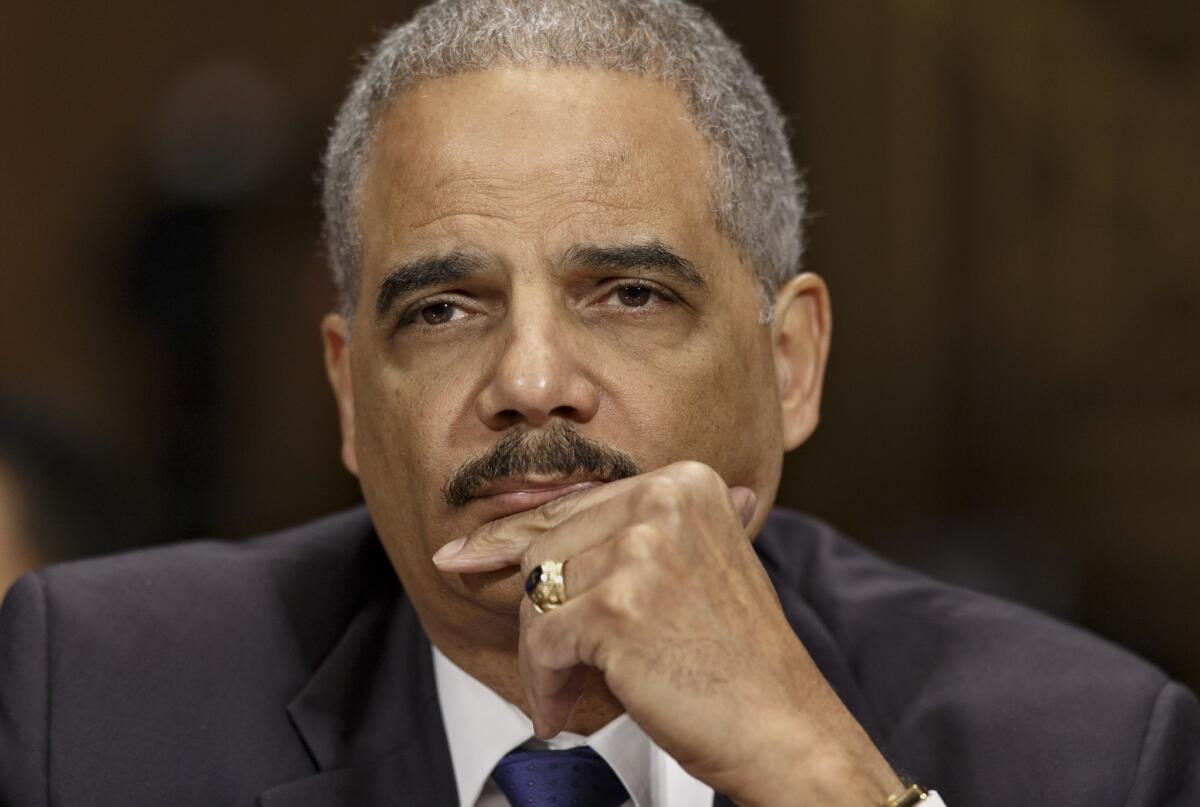

Lending the authority of his office to an important and increasingly bipartisan cause, U.S. Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr. this week called for states to do away with laws that prevent convicted felons from voting even after they have served their time.

In a speech at Georgetown University, Holder noted that an estimated 5.8 million Americans are prohibited from voting because of felony convictions, and said that the impact of such exclusion on racial minorities was “disproportionate and unacceptable.” As a result of such laws, 2.2 million black citizens — nearly 1 in 13 adults — are unable to vote. In Florida, Kentucky and Virginia, the ratio is 1 in 5.

It isn’t just that black Americans are incarcerated at rates higher than the rest of the population. Holder also noted that felony disenfranchisement laws in some states have historical roots in efforts during Reconstruction to “target African Americans and diminish the electoral strength of newly freed populations.”

Holder’s emphasis on the racial implications of these laws is entirely appropriate. It is consistent with other initiatives he has taken to ameliorate disparities in law enforcement, including his directive to federal prosecutors to refrain from charging low-level, nonviolent drug offenders with crimes that would lead to draconian mandatory minimum sentences. Black defendants have disproportionately been harmed by excesses in the war on drugs.

But redressing racial inequity isn’t the only reason for allowing men and women who have paid their debt to society to rejoin their fellow citizens at the ballot box. As Holder pointed out, research suggests former prisoners who had their voting rights restored were less likely to offend again. And, empirical evidence aside, re-enfranchising citizens who have been returned to their communities is a matter of simple justice.

In California, voting rights are restored to felons automatically after their release from prison and discharge from parole. That system is a model for the entire nation. But, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, 11 states permanently bar some or all convicted felons from voting (though most released prisoners can apply for a restoration of voting rights on an individual basis).

As a federal official, Holder has no direct influence over state election laws. And in his speech, he didn’t endorse periodic proposals in Congress to allow offenders who have served their time to vote in federal elections even if they were ineligible to participate in elections for state and local offices. (Enactment of such a law would require states to keep two sets of election ledgers.)

Still, the attorney general delivered a message that state government should heed: that felon disenfranchisement laws “undermine the reentry process and defy the principles — of accountability and rehabilitation — that guide our criminal justice policies.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.