Obama’s peers didn’t see his angst

- Share via

HONOLULU — As a second-stringer for the Punahou high school basketball squad, Barack Obama would fire up his teammates with renditions from the R&B group Earth, Wind & Fire. In yearbooks, he signed his name with a flourishing O, for Obama, which he topped with an Afro. In a world of 1970s rock ‘n’ roll, he was known for a love of jazz.

To his classmates, the skinny kid with a modest Afro had comfortably taken his place in the ethnic rainbow of Punahou, an elite prep school.

Today, Obama is a campaign sensation, in part because he is seen as the first black presidential candidate who might be able to reach beyond race, building support among Americans of all backgrounds.

That capacity does not surprise the students who knew Obama at Punahou School, which carefully nurtured a respect for diversity.

“We had chapel sessions on the Bahai faith, Islam, Judaism, and all forms of Christianity,” said Bernice G. Bowers, a classmate. “The message was that diversity made for a richer community.”

Dressed like other boys in the required collared shirts and khaki pants, Obama was one of a small number of blacks, but the student body included large numbers of kids with Chinese, Japanese, Samoan and native Hawaiian ancestry, as well as many whites.

“We didn’t think about his blackness,” said Mark Hebing, who went to school with Obama for eight years.

As a candidate, Obama is also trying to show that he understands the indignities of racism and the economic troubles that many believe continue to flow from the legacy of slavery.

Punahou was where Obama first awakened to these issues, and to the complexities of being black in America. In his bestselling memoir, “Dreams From My Father,” he writes that during his time at the school -- from fifth grade through his high school graduation in 1979 -- he felt the first stirrings of anger toward whites. He says he also delved into black nationalism.

He also experimented with marijuana and occasionally cocaine, which were prevalent in the ‘70s but presented what Obama in his book calls special dangers for young black men.

Obama’s father was a black Kenyan, his mother a white American from Kansas. He was born in Hawaii and spent part of his childhood in Indonesia before returning to Honolulu and enrolling in Punahou.

Obama says that as he found his way in the world, he learned there were limits to the desirability of advertising his race.

“People were satisfied so long as you were courteous and smiled and made no sudden moves,” he writes in “Dreams.” “They were more than satisfied; they were relieved -- such a pleasant surprise to find a well-mannered young black man who didn’t seem angry all the time.”

Certainly Obama’s classmates had little sense of what he says was going on beneath the surface.

“His reflections about the race issue surprised all of us,” said Kellie Furushima, who knew him well. “He gave no indication of feeling uncomfortable in school, and I never witnessed or heard anyone being unkind to him.

“We liked him very much. I’d poke him in the stomach when he walked by. We’d share a grin and giggle. He seemed to me to be a happy guy.”

Punahou, a day school founded by white Christian missionaries in 1841, reflected the racial composition of Hawaii, with its large white and Asian populations. African Americans made up 1.2% of the population of Honolulu, according to the 1980 census.

Obama seldom encountered the open racial hostility and discrimination that was being expressed in many other parts of the country. Rather, what he experienced were the subtle signals of racial attitudes that others often do not realize they are sending.

Obama writes of being privately offended or even enraged when white classmates adopted black street slang or revealed their underlying consciousness of his race by going out of their way to tell him how much they admired a black musician or athlete.

“Being in Hawaii, we had a lot of different races,” classmate Vernette Ferreira Shaffer said. “People would tell ethnic jokes, but it was more about making fun of stereotypes than trying to do a cool thing.”

Sometimes, the problem took a less subtle form. According to Obama’s memoir, a fellow seventh-grader once called him a “coon.” Obama writes that he bloodied the boy’s nose and got a reaction of surprise: “Why’d ya do that?” the boy asked.

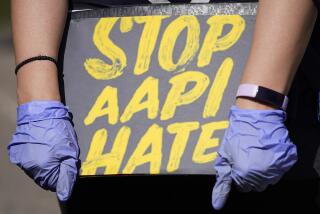

Nor did the insensitivity always involve blacks. Classmate Margaret Hill said many students socialized at a small grocery near the campus that was run by a Chinese couple. It was known almost universally as the “Chinks’ store.”

“It was a great little place, filled with candy, and you could go there and even get little steamed dumplings,” she said. “Every day when school let out, tons of kids headed there. I arranged to have my mom or dad pick me up at the Chinks’ store.”

The name persists today; even some faculty dismiss any suggestion of stereotyping, saying that’s just what the store is called.

Jon Okamura, an ethnic studies instructor at the University of Hawaii whose daughter graduated from Punahou, said that while Obama as a teenager in Hawaii might not have shown his angst, it most certainly would have been boiling inside him.

“There may have been that kind of belief that Hawaii was a racial paradise. But Hawaii in the ‘70s was more like the ‘60s on the mainland,” Okamura said.

Obama’s persona at Punahou gave almost no hint that he felt racial tensions. He seemed to compartmentalize his life, so that his classmates had little or no knowledge of him beyond the school.

Obama lived with his grandparents in an apartment near the school, his father away in Kenya and his mother pursuing studies in anthropology. None of the 40 classmates interviewed for this article -- one-tenth of his class -- saw the inside of that apartment, nor had any idea that Obama came to Punahou only by the grace of financial assistance with the tuition -- $15,000 a year in today’s dollars.

In class, he excelled in debate and composition.

Darin Maurer was amazed at what Obama could get done just over lunch at home. “This was before computers, and he could sit with a typewriter and put down a term paper pretty fast, then head back to school and hand it in.”

Jeff Cox debated him in junior year. The issue was gun control; Obama took the pro-gun side and waxed him. “I thought my facts were going to prove themselves, and they didn’t,” Cox said. “Mainly because he was so good at maneuvering and framing the issue in his favor.”

In Obama’s memoir -- which he says contains pseudonyms, altered chronologies and composite characters -- he writes about using drugs and alcohol to ease the tension he felt.

“Pot had helped, and booze,” he writes. He watches a character -- not identified as a Punahou student -- handle the “needle and the tubing,” his face glistening with sweat as he injects a drug.

“Junkie. Pothead. That’s where I’d been headed: the final fatal role of the young would-be black man,” Obama writes.

In his classmates’ memories, drug use did not set Obama apart any more than his race did. Almost all of those interviewed said they too experimented with illegal substances, were approached by dealers, or at least knew someone who got high.

Pot, grown openly in backyards, was hidden inside boogie boards and smoked behind a Lutheran church near the school. Sometimes it was carried down the hill and traded among the tourists and surfers on Waikiki.

“Pretty widespread,” recalled David Baird. “It was very spread out and very easy.”

Eric Kusunoki was Obama’s homeroom teacher all four years of high school. He saw him every morning, walked with him to school assemblies, attended chapel services with him.

“To say there was a lot of drugs going on back then is a fair statement, maybe an understatement,” the teacher said. “But we didn’t know who was involved or anything, and he was a guy who was very poised and bright, polite and well-liked.

“And this search for his identity? I was totally unaware of any of that in him. That was all new to me.”

richard.serrano@latimes.com

Times librarian John Jackson contributed to this report.More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.