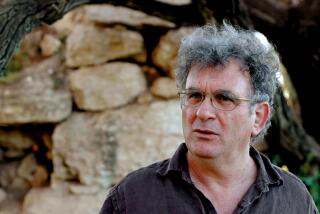

Raul Hilberg, 81; scholar was an authority on the Holocaust

- Share via

Raul Hilberg, who established himself as the preeminent scholar of the Holocaust with his monumental and still-controversial 1961 book “The Destruction of the European Jews,” the first comprehensive study of the Nazis’ genocidal campaign, died of lung cancer Saturday at a hospice in Williston, Vt. He was 81.

A longtime professor at the University of Vermont, Hilberg was considered the dean of Holocaust studies for his meticulous portrait of the “machinery of destruction” that annihilated more than 5 million European Jews during World War II.

“Raul Hilberg’s work and great opus, ‘The Destruction of the European Jews,’ set the standard and created the foundation for the development of the whole field of Holocaust studies,” said Paul Shapiro, director of the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

Hilberg’s groundbreaking book, which drew on mountains of documents from the Nuremberg trials, demonstrated the systematic nature of the Nazi slaughter. He also wrote “Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders” (1992), which examined the vast bureaucracy of accountants, guards, engineers, architects and other anonymous workers whose cooperation enabled German dictator Adolf Hitler’s killing machine to roll relentlessly in service of gruesome ends. In defining what Shapiro called “the three roles of human beings in the genocidal situation,” the latter work created a framework for future scholars to follow.

Hilberg’s primary focus on the perpetrators and some of his conclusions -- in particular, his assertions about the lack of substantial Jewish resistance -- drew sharp criticism from some Jewish historians and the Jewish public, whose attacks continued unabated throughout most of his five-decade career.

He came to his life’s work through tragedy and luck. An Austrian Jew born in Vienna in 1926, he narrowly escaped the Holocaust as a teenager. He witnessed his father’s arrest in 1938 when Germany annexed Austria, but because his father had served in World War I, Nazi policy allowed the entire family to avoid internment by giving up their property and leaving the country.

They fled first to Cuba, then to New York City. After high school, Hilberg was drafted into the U.S. Army and returned to Europe. His division helped liberate the Dachau concentration camp.

He also assisted in the hunt for German documents that could be used in the prosecution of war crimes. While stationed in Munich at the former Nazi party headquarters, Hilberg discovered crates containing Hitler’s private library. He later worked for a project to organize and microfilm captured German documents. That archive became the foundation for Holocaust research, including his own landmark study.

After attending Brooklyn College, he entered Columbia University, where he earned a master’s degree in 1950 and a doctorate in 1955. One of his Columbia professors, Franz Neumann, taught classes about bureaucracy, particularly how the development of a nation like Germany relied on the labor of a vast system of functionaries.

“That idea sparked a similar one in my mind,” Hilberg told the Chicago Tribune some years ago. “I grasped that the Holocaust could only have been possible through the efforts of a similar bureaucracy, which must have left its records too.”

No serious scholars were studying the Holocaust then, so when he told Neumann, who had become his doctoral advisor, that he wanted to pursue it, Neumann told him “It’s your funeral.”

Hilberg decided to focus on the perpetrators of the Holocaust, which he called “the work of a far-flung, sophisticated bureaucracy.” Without an understanding of who carried out the genocide, he later explained, “one could not grasp this history in its full dimensions.”

When he completed his dissertation and looked for a publisher, he was greeted with rejection after rejection. Some publishers found the 700-page manuscript unwieldy. Others didn’t like his reliance on German sources or took issue with his views on Jewish accommodation. He could not find a teaching job until 1956, when he was offered a temporary position at the University of Vermont. After several years, he earned a permanent slot, which would remain his academic home for 35 years until his retirement in 1991.

“The Destruction of the European Jews” was finally accepted by a small Chicago publisher but only after a wealthy patron agreed to purchase 1,300 copies to donate to libraries. Hilberg’s book told a story that many did not want to hear. He carefully chronicled the monstrous nature of the Nazi drive to exterminate the Jews but also argued that Jews did little to help themselves. He contested the widely accepted view that some 6 million Jews were killed, arguing the number was closer to 5.1 million, and he concentrated his analysis on the actions of the Nazis, giving short shrift, his critics said, to the victims. Some of the most pointed criticism came from Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial institute.

Hilberg gave more attention to the victims in “Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders,” but continued to maintain that Jewish resistance was minimal. He was critical of those who preferred “victim-oriented” history, whose views of the Nazi killings were limited by “the fence around the ghetto, and the barbed wire around the camp.”

“The Destruction of the European Jews” was revised and expanded into a three-volume work in 1985 and remains what Shapiro called “the most consulted, fundamental work” in the field. It was later published in Germany, where Hilberg became a popular lecturer addressing a younger generation of Germans struggling to absorb the enormity of their forebears’ ghastly scheme. Last year, Germany presented him with the Knight Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit, the highest tribute given to non-German citizens.

His rising stature in Germany caught the attention of some critics, such as Harriet Lipman Sepinwall, a Holocaust educator who reviewed Hilberg’s memoir, “The Politics of Memory: The Journey of a Holocaust Historian” (1996) in the New Jersey Jewish News.

Reacting to his portrayal of the lonely years of his career before the Holocaust gained widespread scholarly interest, Sepinwall wrote, “It is ironic that his connections with the Holocaust, which initially drove him away from Austria and Germany, now seem to be bringing him back there as the only places where he feels he is not only accepted, but honored.”

In later years, when Hilberg received awards, he said the recognition pleased him. However, as he told a reporter last year, he could never forget one thing: “And that is that the dead are still dead, and it is about them that I think.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.