Editorial: Republicans are wrong: Churches aren’t being muzzled by the IRS

- Share via

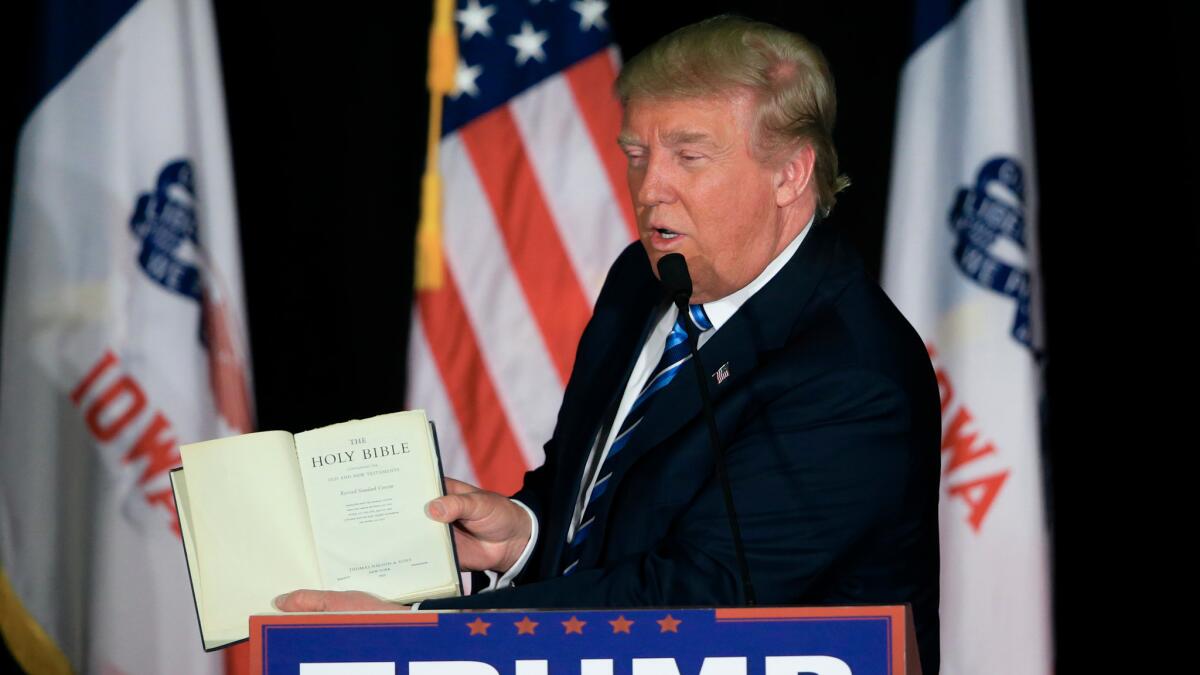

In an attempt to cement support from conservative Christians, Donald (“I love the evangelicals!”) Trump has been promising to seek the repeal of a law that prohibits members of the clergy from endorsing political candidates from the pulpit. “You’ve been silenced,” Trump told 700 pastors and their spouses on Thursday. But he promised that “we’re going to get your voice back.”

Trump is wrong. The restrictions imposed on churches by the law — which also apply to secular tax-exempt organizations — don’t prevent them from speaking out about a vast number of political issues; it simply prohibits them from endorsing or opposing candidates. And even that restriction has been lightly enforced by the Internal Revenue Service, to the benefit of both political parties.

The target of Trump’s criticism is the Johnson Amendment, which was added to the tax code in 1954 at the behest of then-Sen. (and future president) Lyndon B. Johnson. The amendment prohibits so-called 501(c)(3) tax-exempt charitable organizations, secular and religious alike, from participating in any political campaign on behalf of, or in opposition to, any candidate for public office.

The amendment doesn’t prevent priests, rabbis or other members of the clergy from sermonizing about political issues from poverty to climate change to terrorism, nor does it prohibit them from endorsing candidates in their personal capacities. Rather, it says to churches and other nonprofit organizations that if they seek the benefits of tax-exempt status — which can be worth millions of dollars — they must refrain from a subset of political speech. The underlying principle is that when the taxpayers provide a financial benefit to charitable organizations (including religious organizations), they shouldn’t be asked to subsidize political views with which they might disagree.

Nevertheless, many religious leaders — particularly politically conservative evangelicals — have railed against the restrictions as a violation of their 1st Amendment rights. The Republican National Convention that nominated Trump also approved a platform that calls for the repeal of the Johnson Amendment and declares that “the IRS is constitutionally prohibited from policing or censoring speech based on religious convictions or beliefs.”

Some argue that repealing the amendment wouldn’t make much difference because the IRS isn’t aggressively enforcing it. Others point to the fact that most members of the clergy abide by the restrictions. A survey published last week by the Pew Research Center on Religion and Public Life found that 14% of frequent churchgoers reported hearing clergy speak in favor or against a presidential candidate in recent months. (Among black churchgoers, 29% reported hearing a member of the clergy support a candidate, usually Hillary Clinton.)

But even if the rule is mostly being observed, repealing it could embolden more priests and preachers to turn religious services into campaign rallies.

Moreover, at a time when the Supreme Court has equated political speech with spending on elections, churches and other religious organizations might be tempted to involve themselves even more in the political process, and the collection plate could become a conduit for political contributions. The Johnson Amendment should remain on the books, and it should be enforced.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.