Journalists need this federal ‘shield’

- Share via

The notion that society benefits when journalists are able to promise confidentiality to news sources isn’t a radical idea. The vast majority of states provide some protection for reporters from having to identify sources who request anonymity, and long-standing Justice Department regulations require government lawyers to try to obtain information from other sources before issuing subpoenas to journalists or seeking to acquire their telephone records.

Yet attempts to write such protections into federal law have repeatedly foundered, most recently because of a concern in Congress that a federal “shield law” would protect not only journalists but also organizations such as WikiLeaks that indiscriminately and perhaps irresponsibly disseminate classified information. But support for a shield law surged after it was revealed that the leak-obsessed Obama administration had obtained the telephone records of Associated Press reporters and secured a warrant to read the emails of a Fox News correspondent.

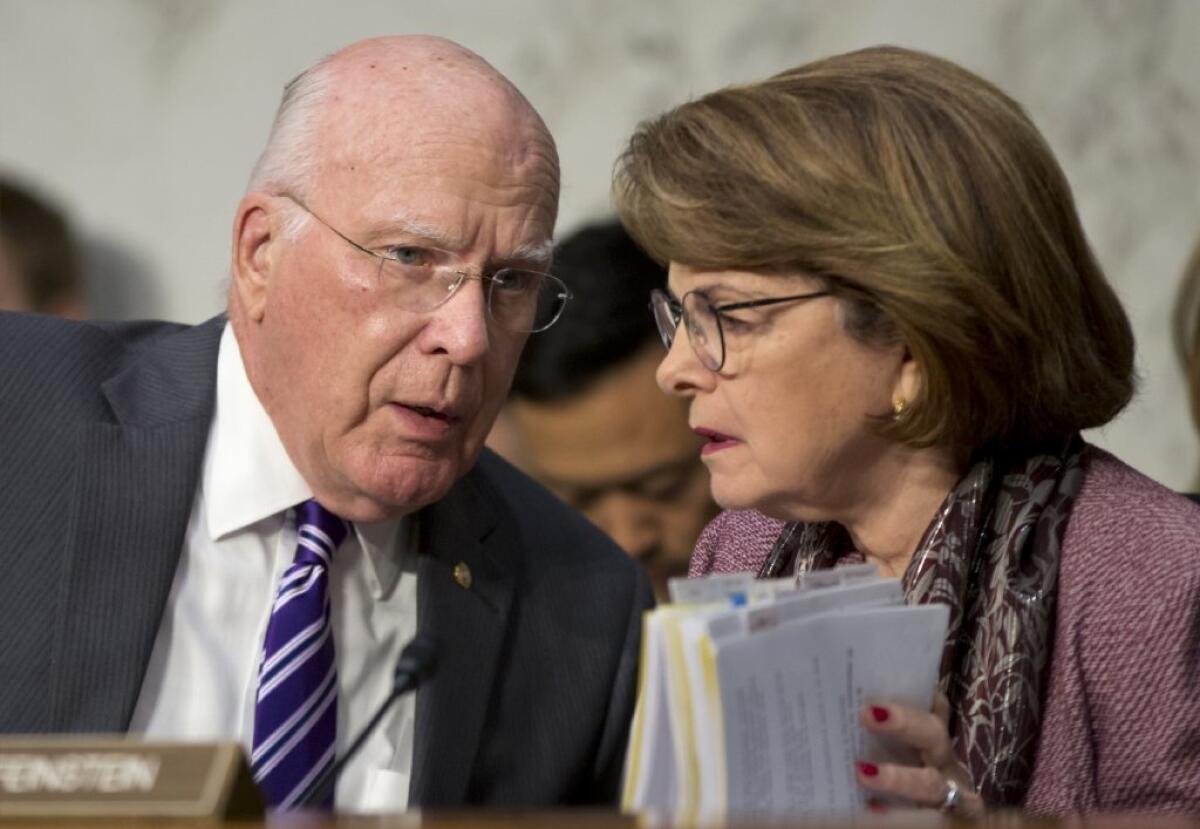

The Senate Judiciary Committee has approved a proposed Free Flow of Information Act that garnered support from all 10 of the committee’s Democrats and three of its eight Republicans. While the bill isn’t exactly the legislation we would have written, it would provide considerable protection for journalists who promise confidentiality to their sources in order to obtain and publish information of public concern.

The bill’s centerpiece is robust judicial review of attempts by the federal government to force journalists to disclose the identity of anonymous sources or documents they promised to keep confidential. A judge could approve a subpoena if the information being sought was essential to the resolution of a criminal or civil case and the government had exhausted other possible sources for the information. But in doing so, the judge would have to weigh the public interest in compelling disclosure against the public interest in “gathering and disseminating the information or news at issue and maintaining the free flow of information.” That balancing act shouldn’t be left to the prosecution.

Some critics claim that the Senate bill protects only the mainstream media. That’s an exaggeration. The committee adopted an amendment by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) that defines the beneficiaries of the legislation more narrowly than we would prefer, but the bill would still protect employees of a wide variety of news organizations as well as freelancers and college journalists, whether they work in print or online. Even a writer who didn’t meet the bill’s definition of a “covered journalist” — one who, say, blogged on a single occasion about a matter of public importance — could receive protection if a judge found it to be “in the interest of justice and necessary to protect lawful and legitimate news-gathering activities.”

Feinstein also persuaded the committee to make it clear that the bill’s protections wouldn’t extend to any “person or entity whose principal function … is to publish primary source documents that have been disclosed to such person or entity without authorization.” This is directed at organizations such as WikiLeaks, which posted hundreds of thousands of documents purloined by Army Pfc. Bradley Manning. The problem with this exclusion is that sometimes making a document public is an act of journalism even if it isn’t accompanied by additional reporting or commentary. We would prefer language allowing a judge to extend the privilege to a WikiLeaks-like organization “in the interest of justice.”

Finally, some critics complain that the bill offers less protection to journalists when it comes to information the government claims is necessary to prevent or mitigate acts of terrorism or other actions that jeopardize national security. The term “national security” is notoriously elastic, but we’re resigned to this provision because it was inevitable that Congress would insist on it. At least the decision on whether the national security exception was applicable would be made by a judge, not by the government on its own.

Ideally, the shield law backed by the Judiciary Committee would be improved in the ways we have suggested. But even in its present form it would represent a victory for both a free press and an informed citizenry.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.