Op-Ed: It’s time for Obama to make Bear Ears in Utah a national monument

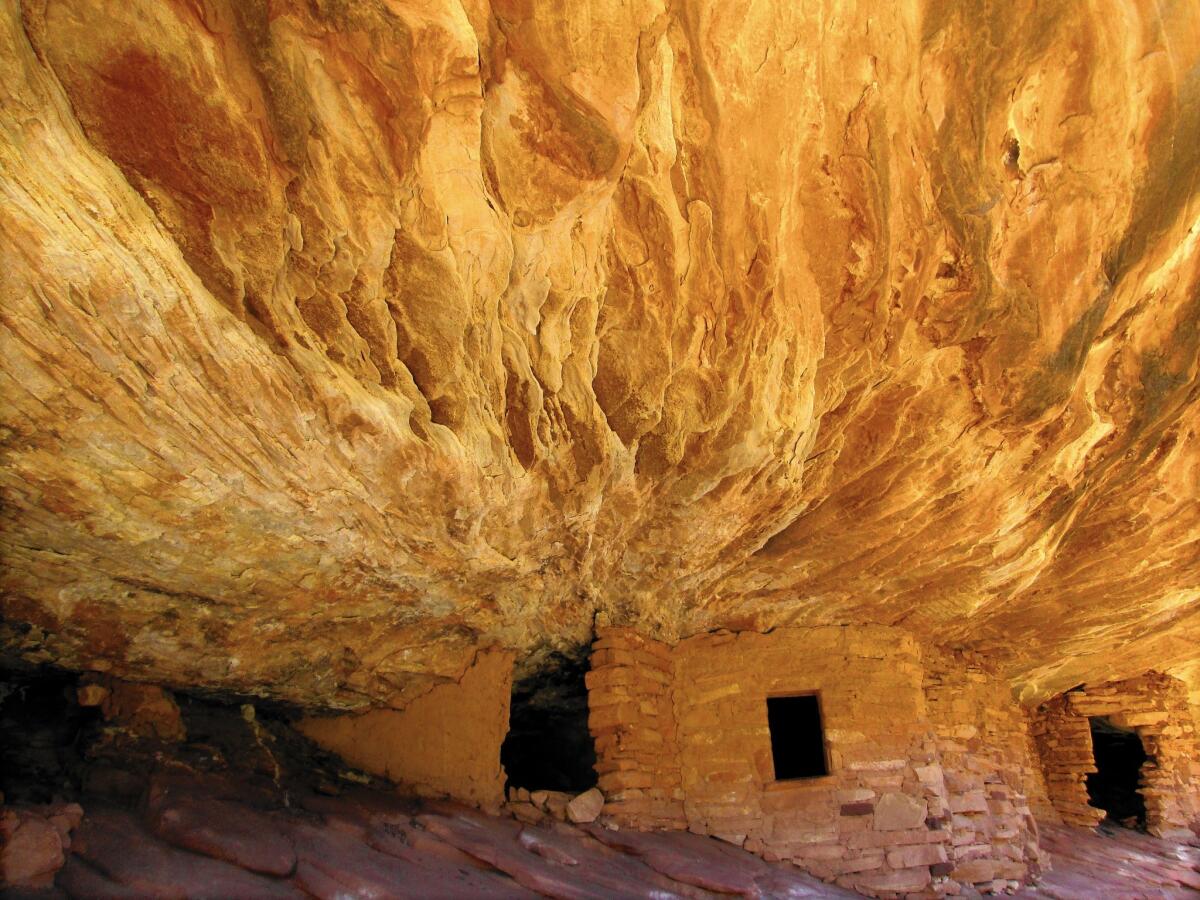

The ‘House on Fire’ ruin, located in Mule Canyon, Utah, is so named because sunlight causes a ‘fiery’ effect over the cliff dwellings.

- Share via

Out west, there’s a group proposing alternative ways of managing federal lands. It isn’t the one occupying that wildlife refuge in Oregon; it’s a coalition of Native American tribes that has proposed a new type of national monument in southern Utah.

Navajo, Hopi, Ute and Zuni tribal members — the original occupants of this region — are seeking, in their words, “to work constructively and respectfully with the Federal agencies” to protect nearly 2 million acres of their ancestral lands.

Navajo, Hopi, Ute and Zuni tribal members -- the original occupants of this region -- are seeking ... to protect nearly 2 million acres of their ancestral lands.

Across the centuries native groups have left evidence of their occupancy in the remains of thousands of stone villages, cliff dwellings, hogans, pit houses and granaries. In recent decades an increasing number of visitors have been drawn to the spectacular landscape in this remote corner of Utah, east of the Colorado River and south of Canyonlands National Park. The region also has attracted vandals intent on grave robbing and looting these prehistoric sites. Miners and ranchers have at times denied tribes access to sacred sites and areas for gathering medicinal herbs and plants.

Tribal leaders are not demanding return of these ancestral lands. They acknowledge that public lands are part of our national patrimony, and should be held in perpetuity for the use and enjoyment of all Americans.

The tribes are, however, seeking a larger role in the protection of their sacred sites and access to places of ceremonial importance. Management of the land, they contend, should incorporate traditional knowledge and respect for the spiritual values inherent in the natural world. In the words of a Ute tribal member, Malcolm Lehi, “We can still hear the songs and prayers of our ancestors on every mesa and in every canyon.”

For nearly five years tribal representatives met with local residents, state officials and congressman Rob Bishop, a Utah Republican who claimed to be drafting consensus land-use legislation that would address their concerns. Talks failed to reach agreement.

So in October the tribes submitted a petition to President Obama, requesting he designate this area a national monument using his authority under the Antiquities Act. It would be called Bears Ears after a distinctive landform rising above Cedar Mesa in the center of the region.

It’s a new model of national monument, however, that the tribes are proposing. Lands currently controlled mainly by the Bureau of Land Management, but also including some held by the Forest Service and the National Park Service, would be jointly administered by a partnership between the tribes and the federal agencies.

The secretaries of the Interior and Agriculture would retain final decision-making authority in the event that management issues could not be worked out at the ground level. Differences would be subject to mediation before final decision by the secretaries. All existing uses and vested rights, including the grazing rights held by local ranchers, would be recognized and protected.

Bishop and the rest of the Utah congressional delegation voiced opposition to the tribal proposal right away. And Wednesday, Bishop finally released a draft of his land-use bill, which would clear the way for accelerated oil and gas leasing and road development.

The Bishop bill then drops a poison pill, by means of a “gag rule” so unusual that it is without precedent in land management legislation. It stipulates that federal agencies cannot consider or take into account any tribal recommendation that has not been endorsed in advance by either the state of Utah or a local county commission.

Bishop’s legislation is a disappointing conclusion after five years of negotiations. Native Americans will certainly see it as a diversionary tactic, designed to forestall a monument declaration by the president.

The next move is Obama’s. To be sure, he should request and consider responses and suggestions from all sides on the tribes’ national monument proposal. He can shape or modify it on many points relating to boundaries, preparation of management plans, dispute resolution and the roles the Forest Service, the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management will play.

But these issues of enhanced land and cultural protection have festered long enough in Utah. The president should resolve them now by creating Bears Ears National Monument.

Bruce Babbitt was secretary of the Department of the Interior from 1993 to 2001.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.