Don’t you dare trust the polls

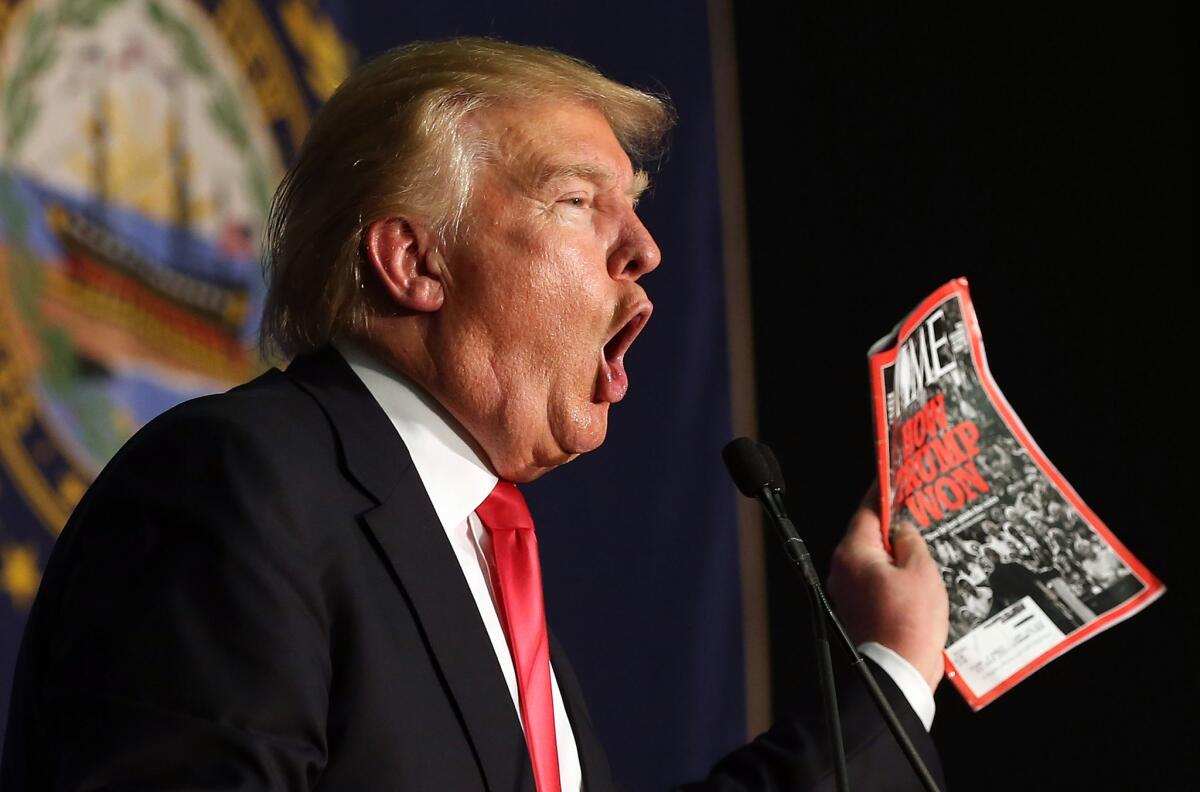

Donald Trump shows off a Time magazine with a cover story titled “How Trump Won” during a campaign event in Iowa on Feb. 2.

- Share via

Over the weekend, I talked to numerous New Hampshirites who don’t have much respect, to say the least, for the science of opinion polling. Many told me they either don’t answer the phone at all or lie to the pollsters. “If someone calls me from the [Ted] Cruz campaign,” one man told me, “I say I’m for [Marco] Rubio.” But, if the Rubio campaign calls, he’s all in for Cruz, or Ben Carson or Donald Trump.

Conversations with local Republican Party pooh-bahs and fellow journalists invading New Hampshire only corroborated my sense that large numbers of people are messing with the pollsters and politicians — and just maybe the pundits, too.

Of course I may be entirely wrong. Such anecdotes don’t have much predictive power. In that, they have a lot in common with the polls.

“So-and-so leads in the polls by 4.5 points” feels so much more empirical than “so-and-so seems to be the one to beat.” But they pretty much mean the same thing.

Everyone in the polling industry will tell you that they’re facing an existential crisis because voters are less willing to answer phone surveys than they once were, and are less likely to own landlines.

Rutgers political scientist Cliff Zukin estimates that landline-only phone surveys miss about 60% of eligible voters. Good pollsters try to compensate by sampling cellphone users, too. (Pew will sample 75% cellphones in 2016.) But that’s more complicated for several reasons: Federal law requires that pollsters dial cellphone numbers manually (no robo calls); people have cellphones registered in areas where they don’t live; and respondents with data plans that count minutes are often unwilling to stay on the phone for very long.

Confronted with these complications, lots of organization fall short or give up on getting the right mix of respondents.

Such problems contributed to the many famous polling failures of late, not only in this country but also abroad. In Greece, Scotland, Israel and Britain, pollsters saw reality go the wrong way. American pollsters completely blew the recent Kentucky governor’s race. And just last week, they blew it in Iowa. Trump was leading in 10 out of 10 polls by an average of seven points on caucus night. He lost to Cruz by three.

The experts have ready answers for why the Iowa polls were wrong. They left out late-deciders, or they didn’t take into account Trump’s lousy ground game. Those excuses may be true, but they are also as unprovable as my claim that the ink in this newspaper serves as a unicorn repellent.

In general, polls sound more scientific than they really are. “So-and-so leads in the polls by 4.5 points” feels so much more empirical than “so-and-so seems to be the one to beat.” But they pretty much mean the same thing. Unfortunately, pundits don’t acknowledge that simple fact enough — not even to themselves — which distorts the conventional wisdom.

An obsession with polling also reinforces simplistic, straight-line projections about how subtle changes in the electorate will affect the outcome of an election. For instance, the punditocracy argued that a big increase in turnout from first-time Iowa caucus-goers would be a sign that Trump would have a great night, because surveys showed he was appealing to political newbies. Wrong. Trump did bring out a lot of new voters, but many of them came out to vote against him.

Despite all these shortcomings, poll-driven thinking dominates the political process (and utterly consumes Trump’s self-image). The season began with access to the GOP debates arranged by standing in the national polls. But that standing derived almost entirely from national name-ID, which could only be remedied by breakout debate performances. Trump, who started out a household name, got outrageously disproportionate amounts of free airtime from the networks. The news outlets justified this gift on the grounds that Trump was the “front-runner” in the polls. And even though Carly Fiorina actually got more votes than New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie in Iowa, she was kept off the debate stage in New Hampshire because of her poll numbers.

We’re never going to get rid of polling — alas — but maybe we’d be better off if we took into account the possibility that just as we can mess with the polls, they can mess with us.

jgoldberg@latimescolumnists.com

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.