Op-Ed: A constitutional convention is the last thing America needs

- Share via

Our new political environment continually prompts the question “Is nothing sacred?” The grudging reverence people of both parties once felt for presidents is gone. Large segments of the electorate categorically deny the entire legitimacy of the last few presidential elections. Since November, there have been repeated attempts to get at President Trump by criticizing his 10-year-old son. In February, the president called the press the enemy of the people.

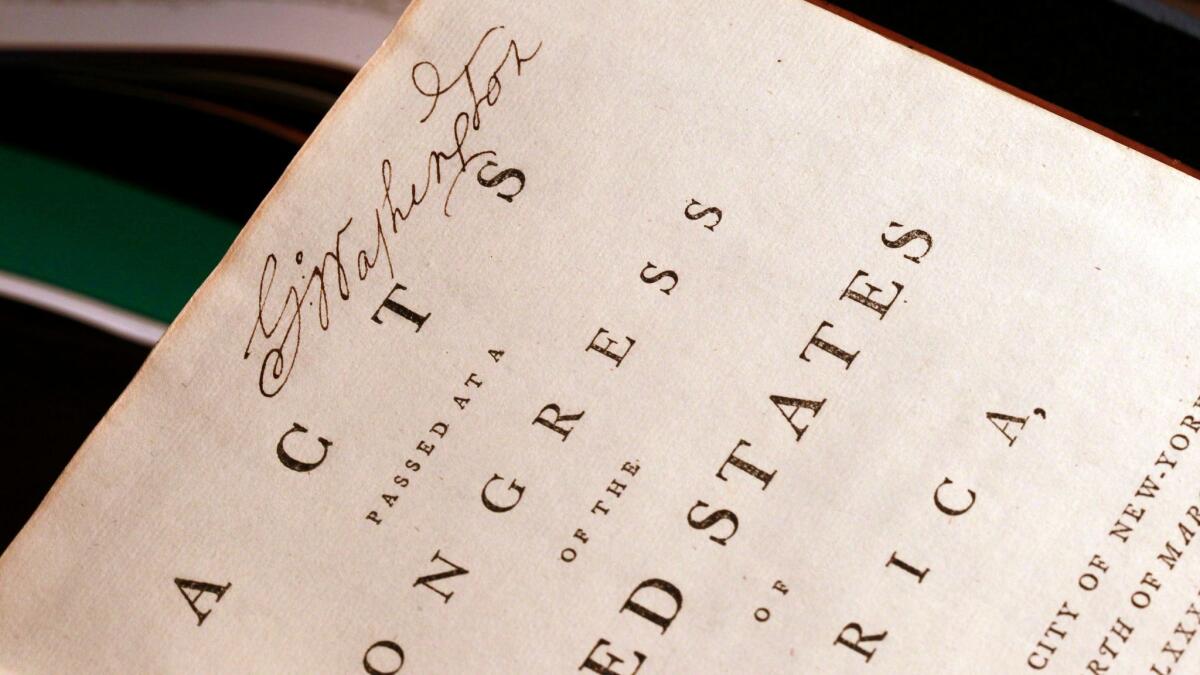

Yet perhaps the most shocking degradation has gone largely unnoticed. This week, Arizona joined the list of states willing to risk turning the United States Constitution — probably the nation’s most important unifying force — into a political football. Arizona asked Congress to call the first constitutional convention since 1787.

Proponents claim they now have 30 states signed up for a “con con,” just four short of the number they need. This involves some pretty funny math. Article V of the Constitution allows two-thirds of the states to come together to direct Congress to call a constitutional convention. Proponents, however, are trying to add 16 state resolutions from a failed convention effort decades ago to 14 resolutions passed over the last few years. With this Congress checking their homework, however, it may not matter.

The Arizona Senate previously voted down a con con resolution by a paper-thin margin (it had previously passed Arizona’s House), and proponents successfully besieged the three Republican state senators who cast the decisive votes to protect our Constitution, flipping two of them. In some places, defense of the Constitution has been more robust: Idaho’s overwhelmingly Republican Senate just resoundingly defeated a constitutional convention bill. But at least a half dozen other states are seriously considering con con efforts.

Given today’s politics, who could be sure that nothing crazy would be successfully proposed, and quite possibly ratified?

With the nation barely a month into the experiment in “shaking things up” that is the Trump presidency, and polarization growing steadily worse, it is remarkable that anyone would think this is the right time to open up our most sacred civic document to the vicissitudes of a convention. Con con proponents solemnly insist, without a shred of legal or historical evidence, that such a convention could be limited to their single purpose: proposing a balanced budget amendment. Proponents also insist a convention would honor current rules requiring ratification of such an amendment by three-quarters of the states.

However, the only prior constitutional convention we have had, in 1787, almost immediately disregarded its charge to merely propose amendments to the Articles of Confederation — and scrapped the Articles’ ratification requirement as well. It turned out OK — the Articles were replaced with the vastly superior Constitution. But the point is this: No one — not Congress, not the Supreme Court and certainly not the president — has any authority to rein in a runaway constitutional convention.

Given today’s politics, who could be sure that nothing crazy would be successfully proposed, and quite possibly ratified?

Conventioneers could employ the age-old practice of logrolling to get their way — combining a conservative proposal (such as the balanced budget mandate) with a liberal one (such as gun control) into a single amendment — no matter how bad or messy the resulting law. Seven of our existing 27 amendments contain at least two quite different provisions.

And even if a con con didn’t hijack the ratification process, a problematic amendment — the authority to suspend the 1st Amendment for national security reasons, say — could still linger indefinitely, only to get pushed over the top by a perceived national crisis or the rise of a demagogue. The 27th Amendment was ratified two centuries after being proposed to the states.

Romantics imagine that a constitutional convention would be a way of taking government back from the politicians. Yet the delegates are likely to be chosen by state legislators, who presumably would select themselves. The representatives you love to hate now — not Madison, Hamilton, Franklin and Washington — would get the chance to revamp the Constitution.

And if that doesn’t scare you, consider what Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger pointed out in 1988: A convention would quickly be saturated in money from special interests seeking to lock their priorities into the Constitution for all time.

A constitutional convention also would circumvent one of the proudest democratic advances of the last century: one-person, one-vote. Without a precedent no one really knows how a convention would unfold, but proponents predict that each state would have an equal vote in whatever they got up to. Great for tiny Wyoming, but not so great for California or New York. Twenty-six states — enough for a majority at a convention — contain just 18% of the U.S. population. A revamped Constitution that small states imposed on large ones would be a festering source of discord.

If voters want more fiscal responsibility in Washington, they need to stop electing candidates who promise huge tax cuts for the wealthy and huge military spending increases without a whiff of an idea how to pay for them. (Whatever you may think of the Affordable Care Act, at least the Democrats paid for it.)

And don’t bring up our duty to future generations: They may not like the national debt we’ll probably bequeath them, but far better that than a ravaged Constitution

David A. Super is a professor of law at Georgetown University.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.