In 1980, Super Bowl XIV between the Rams and Steelers provided a lifeline for U.S. hostages in Iran

- Share via

He endured beatings, mock firing squads and long periods of solitary confinement. His hands were tied behind his back for 30 days in which he was forbidden to speak.

Rocky Sickmann spent 444 days in captivity during the Iran hostage crisis, when 52 Americans were, according to Iranian propaganda, “guests” of the state who were treated with respect. Thirty-five years after his release, Sickmann scoffs at that notion.

“Not a day went by when you didn’t think you were going to die,” said Sickmann, now 58 and an executive at Anheuser-Busch in St. Louis. “Unless you were there, experiencing the sounds and smells, you can’t understand the fear of not knowing if you were going to make it each day.”

Fear was compounded by loneliness, an empty feeling of “knowing the world was going on without you,” said Sickmann, a 22-year-old Marine Security Guard at the time of his capture.

Not a day went by when you didn’t think you were going to die.

— Rocky Sickmann on his 444 days as an Iranian hostage

Former Iran hostage, Rocky Sickmann, left, with Alex Paen, at Super Bowl 50. Paen was able to bring audio recordings of Super Bowl XIV to the hostages.

There were two brief respites, he said. The first came in December 1979, when a large bag of Christmas cards and letters from the U.S. was delivered to the hostages.

The second came in January 1980, when a captor brought a tape recorder into a room, turned it on and told Sickmann and two other hostages — Jerry Plotkin, a Sherman Oaks businessman, and Billy Gallegos, a Marine from Pueblo, Colo. — to listen.

It was a recording of the radio broadcast of Super Bowl XIV between the Los Angeles Rams and Pittsburgh Steelers.

Even though you’re 10,000 miles away, it brought us a small token of home...It brought back wonderful memories . . . it kept me alive.

— Rocky Sickmann on hearing Super Bowl XIV while captive

“We were shocked,” Sickmann said. “Even though you’re 10,000 miles away, it brought us a small token of home. You start thinking about your friends, about every play you made in your high school football games. It brought back wonderful memories . . . it kept me alive.”

As director of military affairs for Anheuser-Busch, Sickmann has attended some 15 Super Bowls since then, and he was among the crowd of 71,088 in Levi’s Stadium on Sunday to watch Denver defeat Carolina, 24-10, in Super Bowl 50.

So was Alex Paen, who in 1979 was the enterprising 26-year-old Los Angeles radio reporter responsible for getting those Christmas cards and Super Bowl tapes to the hostages.

Paen and Sickmann have spoken a few times over the years. But it wasn’t until last month, when they served on a panel to discuss their roles in an NFL Network-produced and George Clooney-narrated documentary titled “America’s Game and the Iran Hostage Crisis,” that they fully explored their link.

Paen, 62, sent a text message to Sickmann during the second quarter of Sunday’s game with instructions on where to meet.

“The text arrived at 4:44,” Sickmann said — the exact number of days he spent in captivity. “It’s like God is on my shoulder giving me a little sign to remind me of how difficult that situation was then, and how wonderful life is now.”

Sickmann spent much of the 15-minute meeting with Paen answering questions about the hostage crisis for Paen’s 16-year-old son, Alexander.

“It’s amazing how God puts people in places for a reason,” Sickmann said. “Little did I know in 1980 that I would be seeing the guy who was responsible for getting those Super Bowl tapes to us, and here I was at Super Bowl 50 with him.”

::

Paen, with a head full of dark curls and a heart filled with wanderlust, was a cub reporter for KMPC radio when hundreds of Iranian militants loyal to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took more than 60 Americans hostage on Nov. 4, 1979.

NFL Sunday telecasts were interrupted with news of the seizure. As footage emerged of angry protesters scaling the front gates of the compound and bound-and-blindfolded Marines, the story grew.

Paen, a Massachusetts native and UCLA graduate, was covering a variety of local stories — city hall, school desegregation, crime, fires, mudslides. He was also a history buff who yearned to see the world.

When Paen learned that Plotkin, a local businessman, was among the hostages, he asked the news director at KMPC if he could go to Iran.

“He looked at me like I was crazy,” said Paen, who has run a Santa Monica television production company for the last 20 years. “He said no, we can’t afford it.”

Paen hatched a plan. KMPC was part of the Gene Autry-owned Golden West Broadcasting network, which had stations in the home regions of five or six hostages. Paen would file reports on them, and the cost of his trip could be spread across the stations.

“The news director said if I could get a visa, I could go,” Paen said. “For one week.”

The day after Thanksgiving, Paen flew to Washington for a three-hour interview at the Iranian Embassy. He secured a visa and flew to Tehran, where the gravity of the situation hit him like a Deacon Jones head slap.

You land at the airport, and it seems like every kid has a gun...There are crowds of people chanting, ‘Death to America!’ It was terrifying.

— Alex Paen

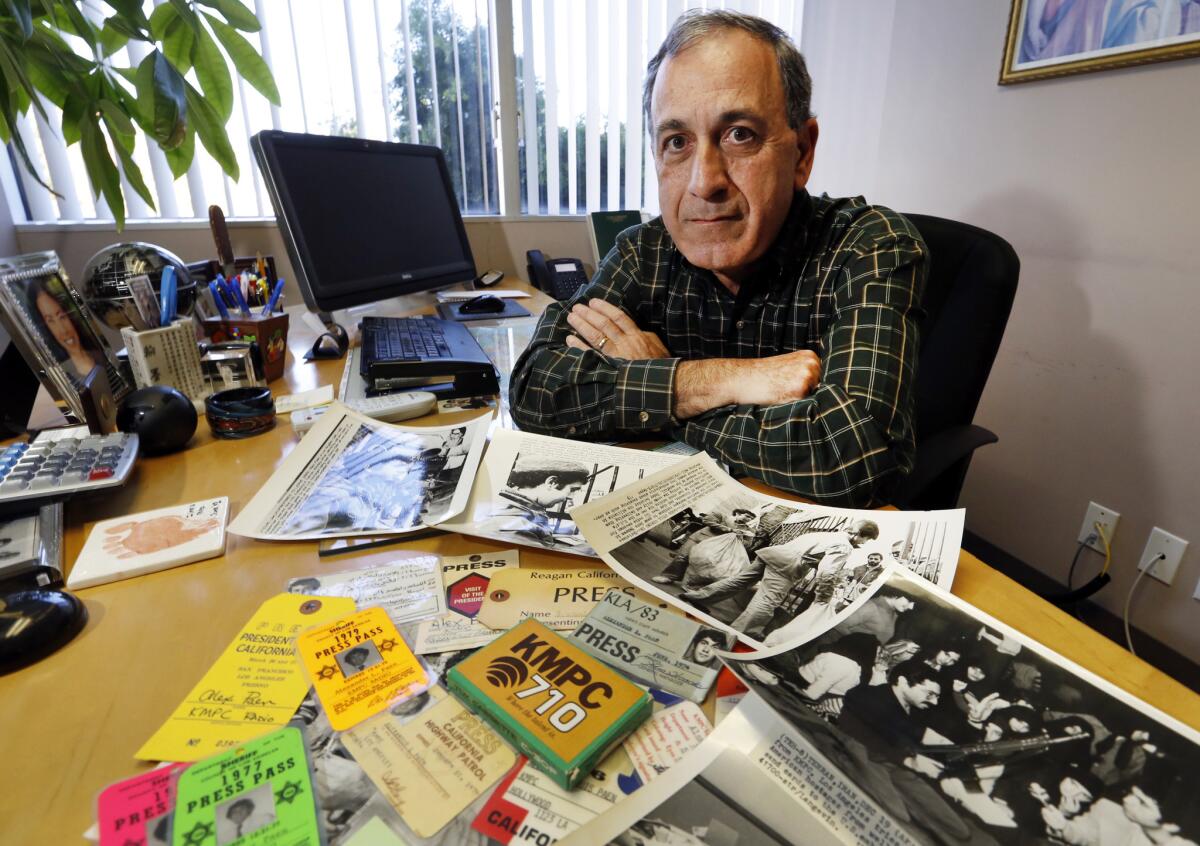

Alex Paen with press passes, photos and memorabilia in his Santa Monica office where he is founder and president of Telco Productions, Inc.

“You land at the airport, and it seems like every kid has a gun,” Paen said. “There are crowds of people chanting, ‘Death to America!’ It was terrifying.”

Paen checked into the Hotel Intercontinental in Tehran and went to work developing sources at the embassy. He patiently waited for crowds to disperse to strike up conversations with militants at the gates.

Paen discovered that some of the gun-wielding guards went to college in the U.S. Some spoke English and were familiar with U.S. sports.

“It being football season,” Paen said, “we talked about professional and college teams in the cities they went to school in.”

In December, Paen said, he convinced a guard to deliver a blank cassette to Plotkin, who taped a message for his family, the first communication from a hostage. Around Christmas, Paen convinced guards to deliver thousands of cards and letters from the U.S. to the hostages.

“I later found out they burned some of them at the post office, and big piles of them went unopened,” Paen said. “But I know some of them got through.”

In mid-January, the fledgling government of Iran, which had overthrown the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, in 1979, ordered U.S. reporters out of the country. Paen needed a plan to stay.

Super Bowl XIV was a week away. KMPC was broadcasting the game, and Paen told the militants at the embassy that he would tape the game for them under one condition — they play it for the hostages.

The guards, who by then were calling Paen “Radio California,” agreed under one condition — that the announcer mention that the game would be heard by the hostages. That way, the militants would come off as “more gracious hosts,” Paen said.

Deal.

As kickoff between the Rams and Steelers in the Rose Bowl neared, Paen was awakened in the middle of the night by a colleague at KMPC.

Paen unscrewed the voice receiver in his hotel phone, attached a pair of alligator clips from his tape recorder to the receiver and remained on the line for more than three hours, taping the game that was relayed to him by phone.

I felt happy that they could forget about their predicament for a few hours.

— Alex Paen

Alex Paen with press passes, photos and memorabilia in his Santa Monica office where he is founder and president of Telco Productions, Inc.

Paen marked the four cassettes, drove to the embassy and delivered them with some confidence — but no guarantee — they would be played for the hostages.

“It was a way, initially, for me to stay in the country longer, but as I thought about it, the real bonus was that the hostages got to hear the Super Bowl,” Paen said. “I felt as a human, and not a reporter, that I was giving them a little sense of joy and a link back home. I felt happy that they could forget about their predicament for a few hours.”

Sickmann doesn’t recall much from the Steelers’ 31-19 win that day.

“I just remember the announcers saying that the game would be broadcast for the hostages,” he said. “It was nice to know they were thinking of us.”

::

Paen was kicked out of Iran a few days after the Super Bowl. He returned in mid-April and was there when eight U.S. servicemen died when their helicopter crashed in a failed rescue attempt of the hostages. He was kicked out again in mid-May and took a job with the ABC television affiliate in Los Angeles.

Paen said he was in Paris, trying to secure a visa to travel to Iran, when the 52 hostages who remained were freed on Jan. 20, 1981, the day President Ronald Reagan replaced Jimmy Carter in the White House.

An NBC camera crew caught an emotional embrace between Plotkin and Paen on the tarmac at Wiesbaden Air Force Base in Germany.

“What you did for us . . . thank you, Alex,” said Plotkin, who died in 1996. “God bless Americans, man!”

Paen spent another 15 years as a television reporter before starting his production company. He has no idea where the Super Bowl tapes are today, and he didn’t think much about them until an NFL Network researcher called him in 2014. His taping of Super Bowl XIV “was only two sentences in my book” about the hostage crisis, Paen said.

But as he watched the documentary, which was released in December, Paen said he felt “a sense of satisfaction and goodness that I was able to do something for fellow Americans who were trapped in such a terrible situation.

“They suffered. They’re the real heroes of this story.”

Twitter: @MikeDiGiovanna

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.