Beyond the little grass shack

- Share via

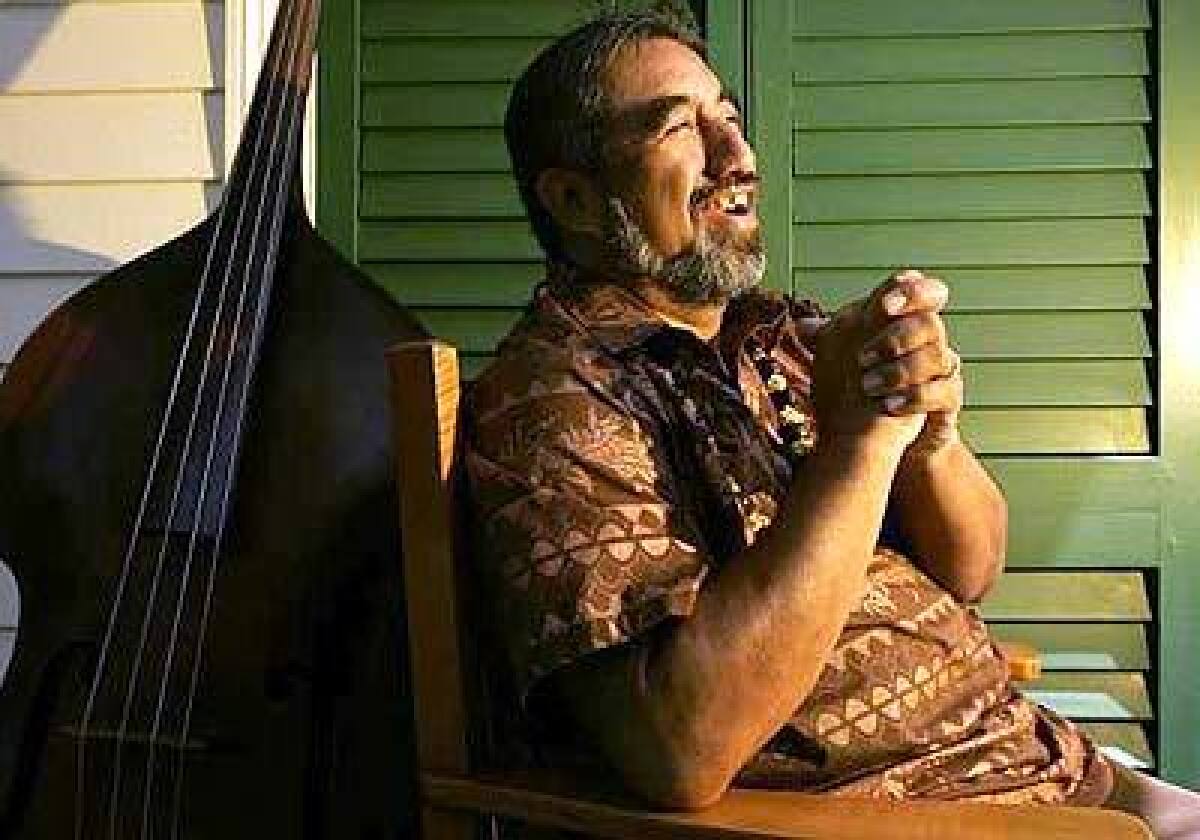

“This is really a ‘woe-is-me’ song,” bassist Aaron Mahi told a crowd at the Waikiki Beach Marriott on a balmy Sunday night. The sun had just set, and a breeze was fluttering the umbrellas on the outdoor terrace. Mahi was introducing “Mauna Loa,” which one might assume to be about the state’s biggest volcano.

But the song really isn’t about the volcano, Mahi explained. It’s about a ship, named after the mountain, that regularly docks at a cove on the Big Island.

But the song really isn’t about the ship either. It’s about a man and a woman and a dawning realization: The man doesn’t have the ipo manuahi — “one and only” love — he once thought he had.

“It seems that she’s not very faithful,” explained Mahi, an erudite Hawaiian with a salt-and-pepper beard, generous girth and mischief in his eyes. “He compares her, with her wide hips, to the wide ship Mauna Loa, which doesn’t always return to the same port. And he compares himself to a handkerchief laced with cockroach holes, good enough only to polish her pointy-toed shoes.”

With that, Mahi leaned back into his chair, set on a makeshift stage decorated with bamboo, thatched grass and striped surfboards. His fellow musicians on slack key and steel guitar dazzled us with achingly sweet chords, and vocalist Martin Pahinui captured all the song’s tender heartache.

I have loved “Mauna Loa” since leaving the islands for college on the mainland 30 years ago. I’ve hummed its lilting melody, memorized its mellifluous syllables and scrutinized many liner-note translations. But it was Mahi, there at the Marriott, who let me in on the mystery of its metaphors.

Much of Hawaiian music is like “Mauna Loa,” an endless well of meaning I can keep dipping into. The lyrics reflect a centuries-old poetic tradition of layered metaphor; their often- bawdy humor would make Chaucer guffaw.

The instrumentation too is endlessly rich: The guitar can be picked in the unique slack key style or pounded in the percussive rhythms of ancient drums. The diminutive ukulele can be plugged into an amp and strummed ferociously. And the steel guitar can moan like a train, clop like a horse or wail like a racing fire engine.

*

Noteworthy history

On a visit here in January, I spent 10 days seeking out such music. I began my crash course in Hawaiian music at an unlikely venue — the Bishop Museum, established in 1889 to house the heirlooms of the last Kamehameha princess.In the stone Hawaiian Hall, I found glass cases full of the instruments Hawaiians used before 1778, when Capt. James Cook showed up in this far-flung archipelago. Drums were complemented by stone castanets, wooden sticks and coconuts filled with seeds. Wind instruments included nose flutes, ti-leaf whistles and a fetching little wood bow that a Hawaiian would press against the lips and talk through.

A music and dance demonstration made clear how ancient chants put meaning over melody: The recitations listed genealogies, praised gods and served as the history books of the Hawaiian people.

Up a dramatic koa wood staircase, displays recounted how Mexican cowboys brought guitars to the islands in the 1830s. Portuguese sugar plantation workers brought the braguinha, which became the ukulele. Calvinist missionaries introduced four-part harmony; from hymn singing, Hawaiians evolved the himeni style.

Heinrich Berger, who arrived from Germany in 1872 to lead the Royal Hawaiian Band, blended the distinct beauties of European and Hawaiian music. Among Berger’s many compositions was “Hawaii Ponoi,” the Hawaiian anthem, whose lyrics were written in 1874 by King David Kalakaua.

Its stirring stanzas remain a standard of the Royal Hawaiian Band, which performs most Fridays at Iolani Palace, the grand Italianate residence now sitting regally amid Honolulu’s government buildings.

The band played under the giant canopy of a monkey pod tree, surrounded by picnicking families, Japanese tourists and matrons in muumuus and kukui nut leis. Its repertoire included compositions by Vincent Persichetti, John Williams, Kalakaua and his sister, Queen Liliuokalani.

The accidental invention of the steel guitar capped Hawaii’s 19th century musical innovations. Legend has it that Joseph Kekuku was in his dorm at the Kamehameha School for Boys when he dropped his comb on a guitar sitting in his lap. Liking the sound, he asked his shop teacher to fashion him a cylindrical piece of steel. (Today’s steel guitars are plucked with the right hand while sliding a steel cylinder along the strings.)The steel guitar soon joined the acoustic guitar, ukulele and stand-up bass, adding the plaintive twang that came to define island music.

Another graduate of the Kamehameha School is keeping the steel guitar tradition alive. Alan Akaka leads the Islanders at the classy Halekulani hotel. The trio mixes traditional melodies with the ditties of Tin Pan Alley. But it is the music of Hawaii’s golden age — the swing era of the ‘40s and ‘50s — that Akaka adores.

The Islanders dress in formal whites, wear classic red feather leis and play under a 120-year-old kiawe tree. For certain songs, hula legend Kanoe Miller joins them, her supple movements animating the lyrics. Watching, I found myself transported to bygone days of elegance and grace.

To Akaka, such time shifting is what the music is all about. “Hawaiian music carries our culture,” he said. “These time capsules, called songs, connect us to our kupuna [elders], to our aina [land]. From chants, you understand what was going on two centuries ago. From “Kaulana Na Pua” [Famous Are the Flowers], written in 1893, you get a vision of members of the Royal Hawaiian Band sitting around lamenting the loss of their queen.”

Throughout the 20th century, trios like the Islanders romanced visitors in Waikiki’s grandest hotels. But in rural Hawaii, something else was up.

Native Hawaiian families were taking the open tunings of Mexican cowboys and inventing their own slack key style of strumming, plucking and adding “chimes,” produced by lightly touching strings at certain frets.

One distinctive family came from the Big Island hamlet of Kalapana. Its scion of the strings is 56-year-old Led Kaapana, an internationally recognized artist who has opened for Bob Dylan and jammed with Taj Mahal.

Kaapana holds forth Tuesday nights at Kapono’s, a bar that juts out over Honolulu Harbor. When I arrived there at 6 p.m., the crowd was sparse. At first the music was subdued, with Kaapana’s clean, bell-like notes energized by his sidekick’s rhythm guitar.

Soon, a crowd of regulars joined three cocktail tables; some were dressed in “Led Head” T-shirts, and some brought boxes of fried lumpia and hot malasadas (soft, hole-less doughnuts).

The sun set in a symphony of golds, the last cargo ships pulled in, and the breeze turned tiki torches into streamers of fire. Off-duty stevedores filled the bar stools, young lovers the oversized bamboo frame sofas.

Kaapana began to improvise, making classic slack key tunes sound sometimes country, sometimes Spanish, sometimes lullaby-like. He strummed, stroked, picked and pulled at his guitar, joking that if you watched his fingers you would learn to mix poi. He sang in baritone and falsetto, told jokes in untranslatable pidgin, and got his Led Heads to punctuate verses of “Hilo March” with a hearty “rah rah.”

*

Return of a tradition

A generation ago it was almost impossible to find guitar playing like Kaapana’s in Honolulu. Then a rough-hewn Hawaiian named Gabby Pahinui hooked up with a ukulele phenom named Eddie Kamae. They played at a joint called the Sandbox and in 1971 released “Sons of Hawaii,” known iconically as the “Red Album.”Just as legendary were the jam sessions held in “Pops” Pahinui’s backyard on Oahu’s eastern shore. The father of 13, Pops let his sons — among them the Marriott’s Martin Pahinui — add rock licks to the music he made with his friends.

Another teenager who cut his chops with Pops was Roland Cazimero. In an interview, Cazimero likened the backyard sessions to “taking the boards” in Hawaiian music.

With jam-session cohort and ukulele wizard Peter Moon, Cazimero conscripted his brother Robert for the group Sunday Manoa. Its first album, “Guava Jam,” hit rock radio stations when I was a teen and brought the music of family gatherings to a new audience.

With the Red Album, “Guava Jam” signaled a new era, the Hawaiian Renaissance. Robert Cazimero remembered it as an all-around awakening. “Music, canoeing, cooking, language, art — everything just stood up and got going,” he recalled.

Today, Hawaiian music is going outside the islands too. “Facing Future,” an album by the late Israel “Iz” Kamakawiwoole, went gold in 2002. Its most popular cut, “Over the Rainbow” — the sweet voice of the 750-pound Hawaiian backed by a plaintive ukulele — has been featured on television and ads. In February, the first Hawaiian music Grammy was awarded to “Slack Key Guitar Volume 2,” featuring the soft, seductive finger-picking style.

The Brothers Cazimero, who were Grammy finalists and remain pioneers, performs their brand of “island contemporary” at Chai’s Island Bistro, a chic Thai eatery with white linens inside and carved teak outside. I sat at the granite-topped bar and sampled duck spring rolls and songs as varied as a driving traditional medley of “Maori Brown Eyes,” the very swing “Sophisticated Hula” and Iz’s “Maui/Hawaiian Sup’pa Man.”

But it was to the Marriott that I returned on my last night in town. Hawaiian music is less a concert experience than a shared experience, its meaning amplified in the back and forth between performer and audience. Aaron Mahi’s explanations reminded us what it is to lust for others, to lament loss, to laugh at our predicament.

There was something else that drew me. The Hawaiian phrase kanikapila means “make music.” To kanikapila is to energetically and unabashedly jam. If someone present is known to dance, she is invited to hula. If someone has a beautiful voice, he is asked to sing. If an accomplished musician is in the house, he or she is asked to sit in.

Guitarist George Kuo spotted “Ben from Brooklyn” in the crowd and invited him to dance a rascally hula about, well, seaweed.

Then he recognized Kaili Hiwa Vaughn, the daughter of Hawaii’s favorite baritone, and called her up to dance a song written by her father. She couldn’t have been more untraditional, sitting with DJ Big Teeze and dressed in a tight-fitting T-shirt that barely met the top of her jeans. But as soon as she took off her shoes and started to move, she left no doubt that Hawaii’s musical tradition continues to be as solid as it is sinuous.

Following the island rhythms

GETTING THERE:

From LAX, American, United, Delta, Northwest, Continental, Hawaiian and ATA offer nonstop flights to Honolulu. Restricted round-trip fares begin at $392.

WHERE TO FIND MUSIC:

Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice St.; (808) 847-3511, https://www.bishopmuseum.org . Demonstrations of ancient and modern music take place at 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. daily. Admission is $14.95 for adults, $11.95 for seniors 65 and older and children 4-12, and free for children 3 and younger.

Chai’s Island Bistro, Aloha Tower Marketplace; (808) 585-0011, https://www.chaisislandbistro.com . The Brothers Cazimero perform 7-8:15 p.m. Wednesdays. No cover charge. Chai’s features traditional Hawaiian music almost every night of the week; consult the website for a schedule.

House Without a Key, Halekulani Hotel, 2199 Kalia Road; (808) 923-2311, https://www.halekulani.com . The Islanders perform 5-8:30 p.m. Mondays and Tuesdays. No cover charge. Traditional Hawaiian entertainment and hula every night.

Iolani Palace, 364 S. King St.; (808) 922-5331. The Royal Hawaiian Band, https://www.royalhawaiianband.com , gives free performances here at noon most Fridays. It also performs free at the Kapiolani Park Bandstand at 2 p.m. Sundays.

Kapono’s, Aloha Tower Marketplace; (808) 536-2100. Ledward Kaapana performs 6-10 p.m. three Tuesdays a month. No cover charge.

Moana Terrace, Waikiki Beach Marriott Hotel, 2552 Kalakaua Ave.; (808) 922-6611, https://www.marriottwaikiki.com . George Kuo, Aaron Mahi and Martin Pahinui play 5:30-9:30 p.m. Sundays. From 5:30 to 9:30 p.m. Thursdays, the 86-year-old Hawaiian singing legend “Auntie” Genoa Keawe plays with her quartet. No cover charge.

TO LEARN MORE:

Oahu Visitors Bureau, (877) 525-6248, https://www.visit-oahu.com or calendar.gohawaii.com/oahu. Its online Events Calendar lists upcoming music shows, festivals and celebrations.

Hawaii Visitors and Convention Bureau, 2270 Kalakaua Ave., Suite 801, Honolulu, HI 96815; (800) GO-HAWAII (464-2924), fax (808) 924-0290, https://www.gohawaii.com .

— Constance Hale

*

To see more photos and to hear the music of the islands, go online to https://www.latimes.com/hawaiianmusic .

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.