A tribute to New Orleans from a local who really knows it

- Share via

My mother called our city New AW-yunz. I say New OR-lens, although New AW-lens or New Or-lee-uns sometimes slides out of my mouth.

A local professor told me New Or-LEENS is the favored pronunciation in a few neighborhoods, but most of us say that only when singing “You know what it means to miss New Or-LEENS” or referring to Or-LEENS Parish. Or when commenting on our fellow New Or-LEEN-ians.

However it’s pronounced, it’s my home. It has its issues as any family does, but there’s nowhere on Earth I’d rather live.

If we don’t know how to pronounce our city’s name, it should be no surprise that although 2018’s calendar is filled with events commemorating the 300th anniversary of New Orleans’ founding, no one is sure of the exact date in 1718.

It’s complicated.

We do know that French Canadian Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville (he and his brother, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, explored the Mississippi River in 1699), defied orders to build the city nearer to what is now Baton Rouge. Instead Bienville chose a crescent in the Mississippi 90 nautical miles north of the mouth of the river.

Bienville made the first cut in the canebrakes before 30 convicts began clearing this “dreadful” site, “prone to flooding and infested with snakes and mosquitoes,” Tulane University professor Lawrence N. Powell wrote in “The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans.”

On the other hand, Powell wrote “its strategic location near the mouth of one of history’s great arteries of commerce was superb.”

Sex, life and death are celebrated as are the New Orleans Saints

These days many of the 391,000 or so who live in New Orleans proper — Orleans Parish — tend to be passionate and tolerant.

We recently elected LaToya Cantrell as mayor, the first black woman to win the seat. Sex, life and death are celebrated as are the New Orleans Saints, a passion often mentioned in obituaries.

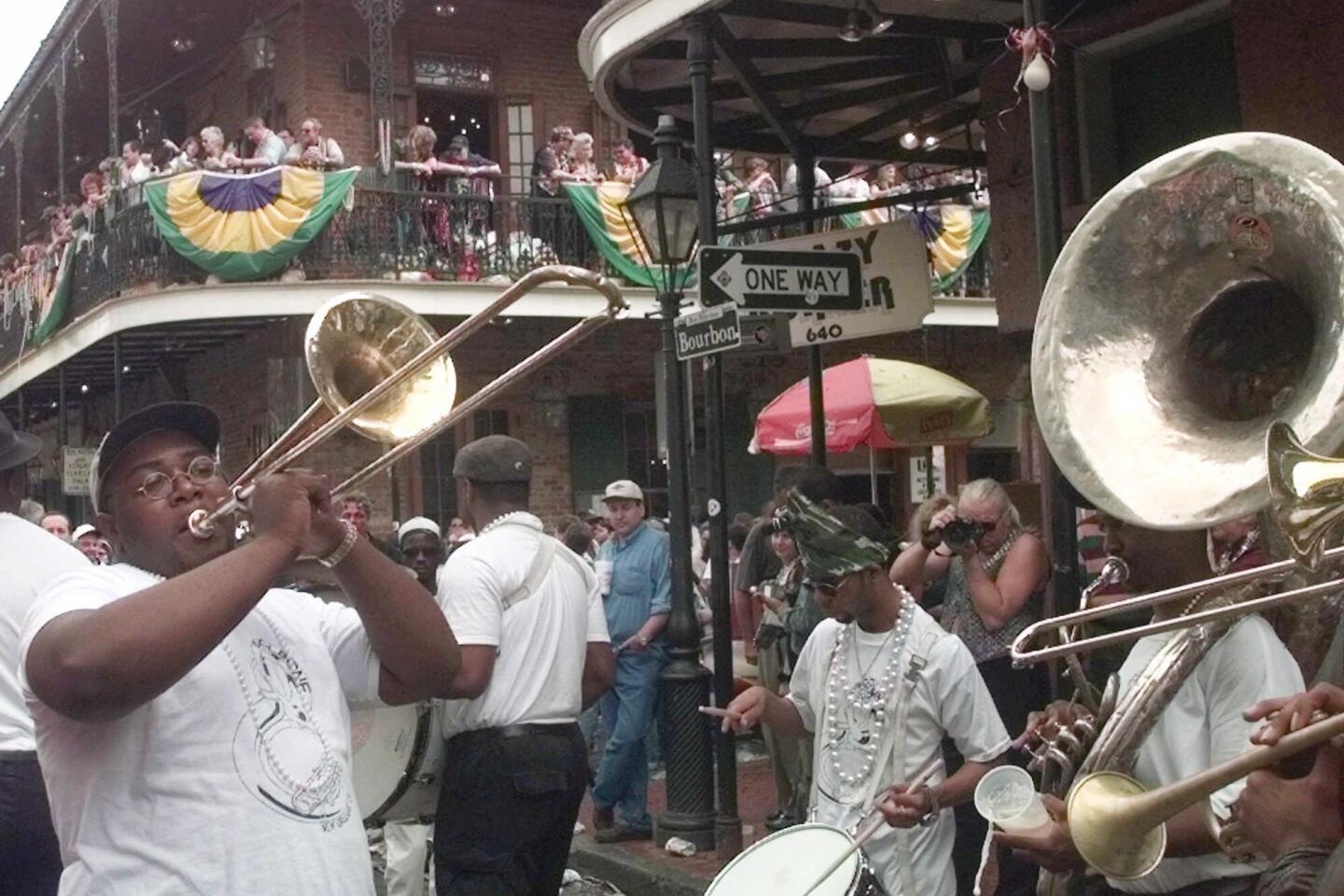

We wave white handkerchiefs in celebration, whether it’s at a concert by New Orleans' “Queen of Soul” Irma Thomas, a winning Saints game or as part of a second line, which refers to anyone marching or dancing behind the first line of family or members of an organization and musicians playing as they walk. The tradition started with funerals of African Americans.

Come anytime, and you’ll find a festival; there are 135 annually. The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival (this year April 27-May 6) is the most revered — and crowded.

Bourbon Street is our most famous name and, “for better or worse, has exported a vision of New Orleans culture around the world,” wrote Richard Campanella, a geographer at Tulane’s School of Architecture who has authored 10 books about New Orleans and Louisiana.

He compares Bourbon Street to Mardi Gras. “Both are spontaneous, bottom-up phenomena, without organizational element,” he wrote. “We’re a place that celebrates pleasure and turns a blind eye.”

Momentum rebuilds

We welcomed 10.45 million visitors in 2016, the most since 2004. On Aug. 29, 2005, levees broke under the weight of Hurricane Katrina and flooded New Orleans for miles between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River. The disaster killed about 1,500 people in Louisiana.

Some in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere said our city should not be rebuilt. Parts of the city are below sea level, and they deemed it doomed.

But come on, New Orleans was hit by a fire in 1788 that flattened 80% of the French Quarter; a yellow fever epidemic in 1853 that killed 8,600 and a total of 41,000 more between 1817 and 1905, and multiple hurricanes.

“Ha!” we spat back. New Orleanians don’t quit.

Three months after Katrina, Ricky Graham, a popular playwright-actor, opened a show called “I’m Still Here, Me!” Audiences cheered when he walked onstage wearing a hat shaped like a roof covered by a blue tarp.

“Thank God for Valium and beer, I’m still here,” he sang. The show ran a year.

It didn’t take long for restaurants to reclaim our attention. There now are about 1,550, and which ones are best is endlessly debated.

Music is another constant topic. Two blocks of Frenchmen Street behind the French Quarter are lined with clubs. Check out Keith Spera’s column at the New Orleans Advocate to see who’s playing there or at Tipitina’s, Chickie Wah Wah or clubs all over town.

The National World War II Museum is our most popular attraction, drawing a record 706,664 visitors in 2017, more than 6 million since it opened in 2000.

Sooner or later everyone ends up in the French Quarter, walking on replacements of those streets laid out by slaves and convicts.

A riverfront park is underway, and when finished in 2019 or 2020, the 3.2-mile walkable park from Bywater to Canal Street will be one of the longest riverfront parks in the country.

Long a melting pot

If you ask locals to talk about their city, expect different responses. What we say depends on our age, family, where we grew up and where we live now: Uptown, Downtown, French Quarter, Marigny, Bywater, Treme, the Irish Channel, University area, Garden District, Gentilly, the Ninth Ward, Lakeview, Chalmette, Algiers, Broadmoor, Eastern New Orleans, a half-dozen more.

Post-Katrina it appears that young Brooklynites have embraced us, many moving to Bywater, the hip neighborhood du jour.

New Orleans has a history of influxes from population pools, said Campanella, a Brooklyn native.

“Sicilians were new once, and now we embrace their muffalettas and red gravy,” he said.

Before them were the Irish and the English and the French and Germans as well as the Spanish. Native Americans were in the area before Europeans arrived.

Slaves were brought here in 1719, the year after the city was founded; part of New Orleans’ shameful past is as a center of slave auctions.

Transplants especially preach the idea that New Orleans is unique among cities, Campanella said. That’s partly why in the 1960s people began referring to those hot squares of fried dough at Café du Monde as beignets — because they were different.

And in the 1970s preservationists and real estate agents began calling Orleans Parish neighborhoods faubourgs, a French word for suburbs.

“It’s true we see Carnival beads hanging from trees and join second-line parades, but we’re still buying frozen food at Walmart,” Campanella said.

He first visited in 1991 and was overwhelmed by the “complex beauty of the built environment, the architecture, the whole ensemble, streetcars, urban foliage, neighborhoods, all of it together.”

He also cited our fascinating and complicated history, replete with triumph and tragedy.

“It continues to intrigue me,” he said. “And the more I learn about the city, the more I don’t know.”

Me too. But just as you don’t have to understand a person to love him or her, you can embrace a city without fully understanding why.

Carnival speak

Mardi Gras is a single day, two days from now. The season is Carnival, with a capital C, and lasts from the 12th night after Christmas (Jan. 6) through Mardi Gras, which is 40 days before Easter. Mardi Gras is the last bash before Lent begins the next day, which is Ash Wednesday.

Carnival parades start two weekends before Mardi Gras.

Most New Orleanians are fluent in Carnival speak. For example, a cousin told me, “I’m riding Chaos, fourth float, second position, neutral ground side.”

Translation? He’s a member of a men’s krewe, a private club called Chaos, sponsoring a parade and/or ball, and will be the second masked or costumed person on the fourth float, left side if you’re walking in the same direction as it rolls (another word) through the street. If he were on the right, he would say he’s on the sidewalk side.

New Orleanians call all street medians neutral grounds. (It’s a long story.) Streetcars run on the neutral ground of St. Charles Avenue, which is part of the traditional route of Carnival parades. We always refer to the left side of the float as the neutral ground side even on streets where there is no neutral ground.

Friends and family members tell you where they’re riding in a parade is so you’ll know when and where to scream their names, your arms outstretched to snap the “throws,” the generic name for the beads, stuffed animals, toys, doubloons, plastic cups and whatever is big that Carnival season that members buy to pitch to the crowds, called revelers.

Sure they could give them to you in advance of the parade, but that’s no fun.

Exceptions to advance gifting are these coveted throws: decorated coconuts from the Zulu krewe, creative purses from Nyx and glitter-covered shoes from Muses.

I like watching parades along St. Charles Avenue near Napoleon Avenue. But many pack Canal Street and afterward the French Quarter.

If you go

THE BEST WAY TO NEW ORLEANS

From LAX, Delta, Southwest and American offer nonstop service to New Orleans, and United, Southwest, American and Delta offer connecting service (change of planes). Restricted round-trip airfares from $218, including taxes and fees.

A native’s favorite places

For traditional New Orleans jazz

Preservation Hall, 726 St. Peter St., (504) 522-2841. Open nightly; call or check the web for show times. $20 for one 45-minute show; cash only. Advance Big Shot admission, $35-$50 provides a reserved seat and no waiting in line. Locals and tourists have jammed this hot spot since 1961.

Palm Court Jazz Cafe, 1204 Decatur St.; (504) 525-0200. 7-11 p.m. Wednesdays-Sundays. Cover charge $5. Entrees from $17. Dine on Creole cuisine while listening to traditional jazz.

Kermit Ruffins and other popular musicians

Ruffins shows up all over town with his trumpet and big smile, including Kermit’s Treme Mother in Law Lounge, 1500 N. Claiborne Ave.; (504) 814-1819; Bullet’s Sports Bar, 2441 A.P. Tureaud St.; (504) 948-4003; and Blue Nile, 532 Frenchmen St.; (504) 948-2583. Track Ruffins’ calendar.

All things Audubon

Audubon Park, 6500 Magazine St., (504) 861-2537. Open 5 a.m.-10 p.m. daily. Free. The 350-acre Audubon Park has sprawling oaks, a 1.8-mile walking loop, lagoon, public golf course and picnic shelters.

Audubon Golf Club Cafe, (504) 212-5282. In good weather, locals fill porch tables at the Audubon Golf Club Cafe. Open 11 a.m.-3 p.m. Mondays-Fridays and 10 a.m.-2 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. Entrees from $11.

Audubon Zoo, (504) 861-2537. 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays; 10 a.m.-5 p.m. weekends. $22.95 for adults, $19.95 for 65 and older, and $17.95 for children ages 2 to 12. On the river side of Magazine Street. Take the St. Charles Avenue streetcar, walk through the park to the zoo.

Garden District

Commander’s Palace, 1403 Washington Ave.; (504) 899-8221. Before or after daily lunch or brunch at Commander’s Palace, meander around the Garden District, NOLA’s poshest neighborhood. Author Anne Rice used to live at 1239 1st St.

Lafayette Cemetery No. 1,1400 Washington Ave. 7:30 a.m.-3 p.m. Square block of tombs dating to 1832.

The Rink, 2727 Prytania St., is a small shopping center with the independent Garden District Book Shop, Still Perkin’ coffee shop, Judy at the Rink gift shop, Mignon children’s clothing, and Adorn & Conquer, my go-to spot for unique jewelry and other items by local artists. All close about 6 p.m.

Outdoors

Crescent Park, 2300 N. Peters St.; (504) 522-2621. This newish park, set beside the Mississippi River in the popular Marigny and Bywater neighborhoods, is what some call the High Line of New Orleans. Stroll among trees and plants, bikers, walkers and watch the river and its ships. It’s the far end of an eventual park that will stretch from Bywater to Canal Street by 2019 or 2020.

Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden, 1 Collins Diboll Circle, (504) 658-4100. Free. A retreat with 64 sculptures set among oaks and a lagoon on five acres adjacent to the impressive New Orleans Museum of Art.

Where to eat

Upperline and Dooky Chase restaurants serve excellent Louisiana food and are owned by ebullient women who display their fab local art collections and have been recognized by the James Beard Foundation. They are where I take out-of-town friends.

Upperline, 1413 Upperline St. (Uptown), (504) 891-9822. Open 5:30 p.m.Wednesdays-Sundays. JoAnn Clevenger wears a black and red dress most nights as she welcomes guests to her 35-year-old restaurant from her stool by the front door. It’s still a favorite of New Orleanians, who feast on duck étouffée and sublime bread pudding.

Dooky Chase’s Restaurant, 2301 Orleans Ave. (near the French Quarter); (504) 821-0600. Lunch and buffet, 11 a.m.-3 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays; dinner 5-9 p.m. Fridays. Leah Chase, who celebrated her 95th birthday Jan. 6, greets diners (who ask to meet her) with a huge smile after they’ve eaten her fried chicken and greens. Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama ate here, as did leaders of the civil rights movement. It was the only restaurant in New Orleans where black and white leaders could eat together.

TO LEARN MORE

New Orleans Tricentennial, 2018nola.com

Tricentennial Symposium: Making New Orleans Home. Free lectures, panel discussions, parties and concerts throughout the city.

New Orleans, the Founding Era, Williams Gallery of the Historic New Orleans Collection, 533 Royal St. Free. Feb. 27-May 27.

“New Orleans & the World: 1718-2018 Tricentennial Anthology,” Louisiana Endowment for the Humanitiescq

Richard Campanella’s 10 books about New Orleans include “Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans”; “Bourbon Street: A History”; “Lost New Orleans; and “Cityscapes of New Orleans”

“The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans,” by Lawrence N. Powell

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.