Volunteer Program’s Success Story : Lawyer, Man She Helped Honored by Parole Group

- Share via

Kathy Gilmore knows the value of friendship. Growing up poor in Memphis, Tenn., she was befriended by a physician and his family and shown another side of the world.

“It broadened my horizons,” said Gilmore, now a hearing officer for the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission in San Diego. “I was going to college, and all of a sudden I wanted to go to Yale.”

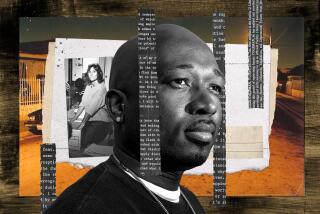

Because someone befriended her, Gilmore did go to Yale, and she became a lawyer. And that is why she later welcomed the chance to become friends with Terry Tisdale, 21, who had spent more than two years in California Department of the Youth Authority institutions for his involvement in an armed burglary, robbery and kidnaping.

They met last year through Volunteers In Parole (VIP), an 11-year-old program operated by the youth authority and the San Diego County Bar Assn. that matches parolees with attorneys in hopes of providing a role model for youngsters emerging from state custody.

On Thursday, Gilmore and Tisdale were honored at a luncheon for their achievements in the program--Gilmore for working with as many as three parolees at a time, Tisdale for the strides he has made in the 2 1/2 years since his parole from the Mt. Bullion Youth Conservation Camp in Northern California.

“I was just trying to be tough, trying to be an outlaw,” Tisdale said, explaining his involvement at 17 in the crimes that cost him 29 months of freedom. Now he is enrolled part time at Southwestern College in Chula Vista, studying business administration, and is working full time as an auditor for a local firm.

“His turnaround was rather dramatic,” said Dolores Fend, Tisdale’s parole agent, who has recommended that he be discharged from parole next week. Tisdale made “that adjustment in his mind as to what he wanted to do and what he didn’t want to do,” Fend said. “And he hasn’t been involved in any trouble since.”

Tisdale attributes at least a little of his resolve to his VIP-initiated friendship with Gilmore. “We talked and talked,” he said.

It is with just such opportunities that the program records its successes, according to Samuel Besses, VIP’s one-man staff in San Diego and the person responsible for matching parolees with attorneys.

“If it does nothing more than provide a sounding board for a youngster who has no one else to talk to, it’s accomplished a great deal,” Besses said. “These kids are treated as worthless. If it improves their feeling of self-respect, self-esteem, then we’ve accomplished something worthwhile.”

The youth authority has launched a study comparing the recidivism (backsliding) rate of parolees who participate in VIP with the performance of those who don’t. Even without statistics, though, officials are confident the program has made a measurable impact.

“It has meant a lot in helping the youngster that might otherwise, without the help of his volunteer and his parole officer, be in San Quentin, or dead, today,” said Wilbur Beckwith, deputy director of parole services for the Department of the Youth Authority.

VIP programs operate in seven urban centers in California, though only San Diego’s makes exclusive use of lawyers for matches with parolees. “Because of their experience, their background, they’re better able to give the sound advice these youngsters sometimes require,” Besses said.

But many young offenders are distrustful of lawyers, he acknowledges, a fact that may help explain why just 15% of the youths eligible for the program choose to participate. Some matches fail because the lawyer and parolee fail to hit it off, Besses said, and only about 50 of the 350 Youth Authority parolees in San Diego County are in matches at a given time.

“A lot of youngsters are very sour on attorneys,” he said. “They may feel the attorney is responsible for putting them in jail in the first place. Their experience with their own attorney is unsatisfactory. They ask, ‘Why should an attorney want to do something for me for nothing?’ ”

The answer is that the lawyers get something back, according to Alex Landon, executive director of Defenders Inc. and one of the founders of the local VIP program. “You get a great deal of satisfaction, in that you can say you may have helped someone,” he said.

Besides, the parolees don’t ask for much, Gilmore added.

“They’re just looking for acceptance,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.